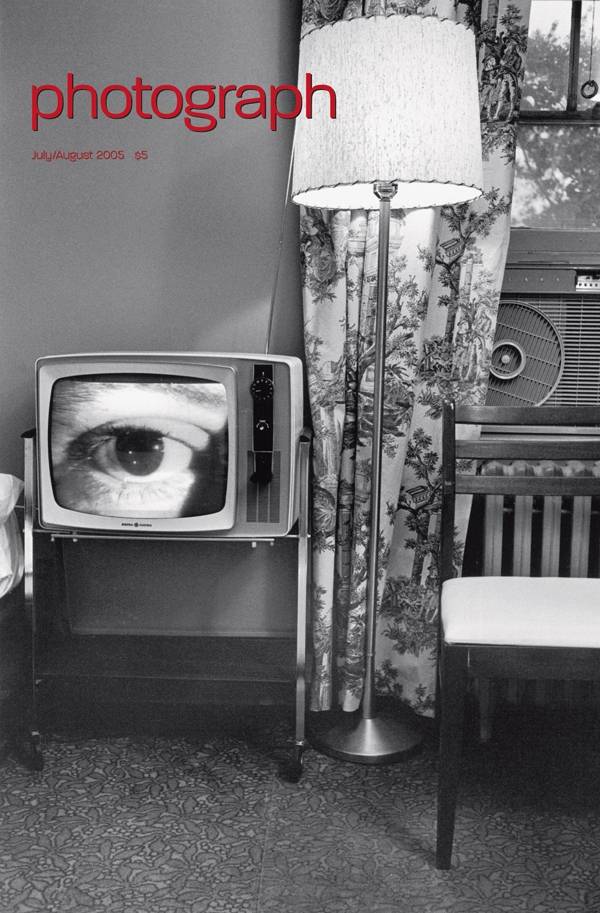

Almost since photographers began to look at the world, they began to look at us looking at (and representing) the world. Images about images have abounded, from the reflections of the photographer in mirrors and windows to the billboards of Walker Evans. By the time Lee Friedlander began to photograph, we lived in a thoroughly mediated world. Television had become the avatar of that Pop consciousness, a ubiquitous and yet still alien form of representation. Other photographers, like Robert Frank, noted it in passing, but it was Friedlander, in the confrontational formalism of his youth, who fixed the image—spectrally but indelibly. Washington D.C., 1962 is one of nine such photographs in the tidal wave of 483 pictures that make up his massive retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, on view through August 29. It reveals Friedlander, America’s roving eye, to be perhaps the most omnivorous, variegated, and insightful photographer America has ever produced. Curator Peter Galassi had been planning the exhibition off and on since MoMA acquired over 800 prints from the artist in 2000. “What the show presented to me as I put it together,” he remarks, “was a career that encompasses all the possibilities of photography, from flat-footed documentary to wisecracking to the purely sensuous. He simply gobbled up the history of photography.” Indeed, during the 1960s, an amazing decade of work, Friedlander channeled Brassai, Atget, Frank, Evans, the Neue Sachlichkeit, and much else besides. It came out as a series of broken rules, decapitation cropping, elaborate frames within frames, images that collapse into their reflections, and signs that threaten to overwhelm the world of actualities. Friedlander was freelancing at this time, and it is almost as if he took revenge on the correctness of his magazine work. He fits right in—almost—with the Pop pasticheurs of the time, Rosenquist, Warhol, and the like, but in hindsight his work appears far more complex and daring. By the late 1970s, things in America calmed down considerably, and they did for the photographer, too. His pictures display less bravado and closer attention, but the habit and hunger for complexity is always there, even in the most straightforward photos. In the early 90s, Friedlander exchanged his 35mm camera for a square-format Hasselblad and has developed an ever more meditative relationship to reality. His late landscapes are sensuous, yes, but almost unreadable. The Ansel Adams-ish grandeur lies beyond the tangle of foreground thatch, out of reach. Many artists arrive at a point where they give up on the world and its appearances; Friedlander has done the opposite, planting himself and asking the camera to do more than it can do, to take him into the picture. And this exhibition, for those sturdy enough to traverse the whole of it, is the way to follow him there.

Categories