In the waning days of April 1975, North Vietnamese soldiers pushed toward Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City), the then-divided nation’s largest city, determined to expel American forces. Recognizing, finally, that the American presence in Vietnam was dangerously untenable, U.S. Marines executed a harried mission to evacuate American civilians and endangered South Vietnamese citizens by helicopter. When North Vietnamese forces seized Saigon, the war officially ended, yet it ushered two societies into a dark night of the soul that may never be fully resolved.

In his multidisciplinary practice, Vietnamese-American artist Dinh Q. Lê addresses memory, displacement, and trauma – but also offers glimpses of hope – in works that frame individual and collective experiences of what the Vietnamese call “the American War.” Lê’s family fled their Mekong River Delta home before violent clashes between Vietnamese forces and the Cambodian Khmer Rouge in 1978, eventually settling in the United States. Almost two decades later, in 1996, Lê moved back to Vietnam and now lives and works in Ho Chi Minh City. His eighth solo exhibition at P.P.O.W. Gallery in New York opens in March, and True Journey Is Return, an expansive retrospective of his work, is on view at the San Jose Museum of Art in California through April 7. The first large-scale exhibition of his work staged in the United States in a decade, it confronts the extreme existential conditions of those who stayed and those who fled.

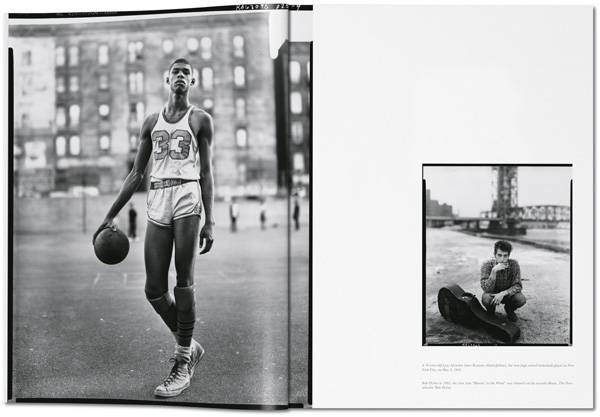

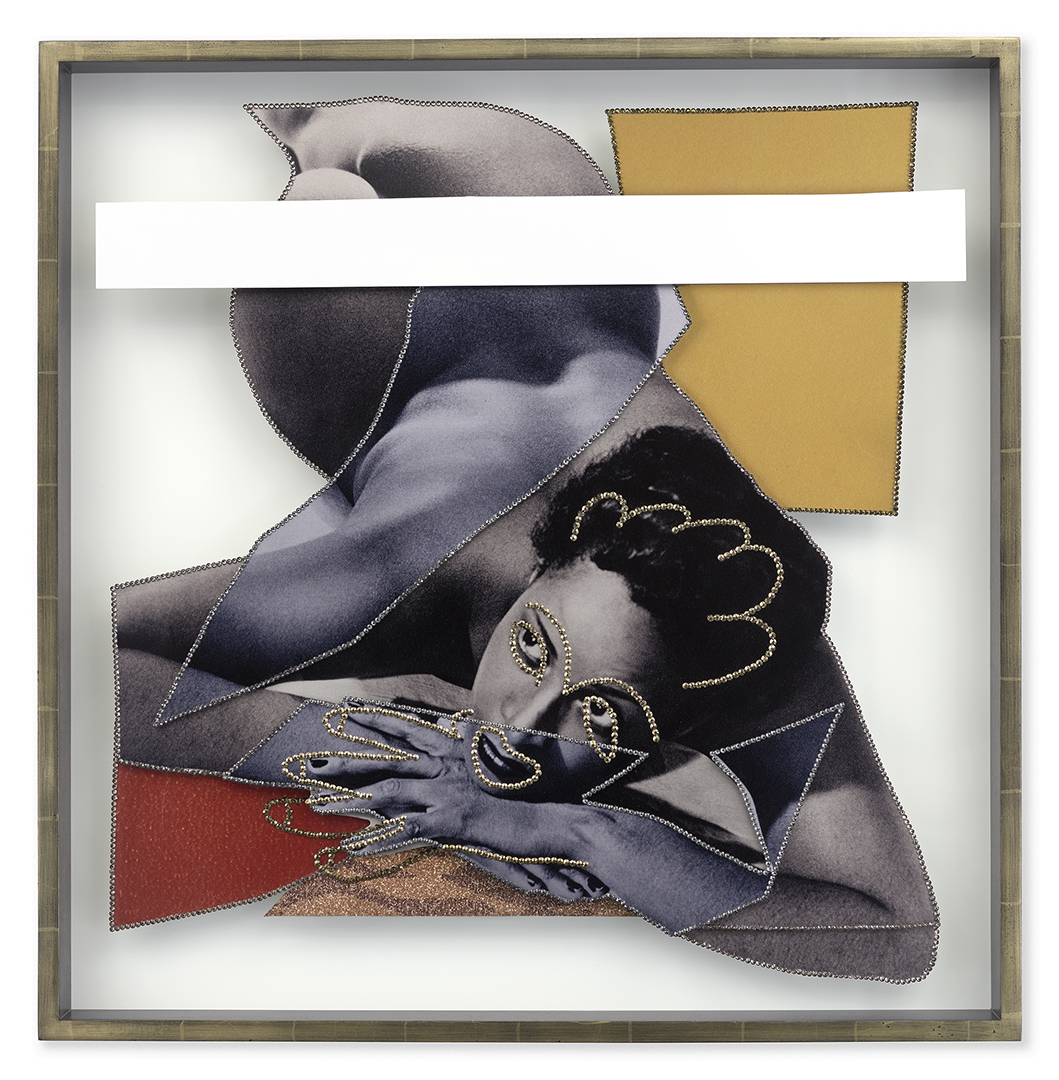

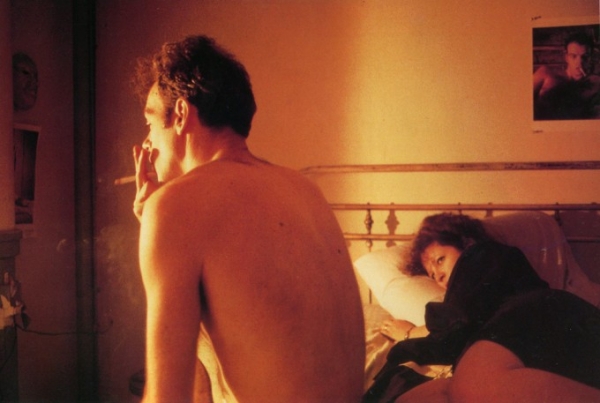

Lê earned fame in the western art world in the early 2000s, with exhibitions at galleries in California and New York (including a solo show in 2005 at the Asia Society) and a 2010 show as part of the Projects series at the Museum of Modern Art. These exhibitions introduced viewers to his photo collages, whose form is inspired by Vietnamese mat-weaving techniques, but which combine journalistic photography and scenes from popular American films that portray the war from an imperialist perspective. The artist cuts the disparate photographs into thin strips and then weaves them together to form a dense composite image. In Persistence of Memory #10, 2000-01, image strips of the iconic scene from Francis Ford Coppola’s film Apocalypse Now, in which American soldiers slaughter Vietnamese villagers from helicopters as Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” reaches its lurid crescendo, are woven together with black-and-white images of anonymous people surrendering. Stand too close or too far from the piece, and the composition eludes legibility. Lê has created a powerful metaphor for understanding the conflict, or not, depending on our willingness to engage the subject psychologically.

The Vietnam War was comprehensively covered by western media outlets, so much so that media access was severely curtailed during the first Gulf War in an effort to forestall the violent public backlash that undermined the war effort in Southeast Asia two decades earlier. Images captured by photojournalists – including such well-known photographs as Eddie Adams’s picture of the South Vietnamese police chief summarily executing a Viet Cong prisoner, and Nick Ut’s shot of the naked nine-year-old girl screaming as she runs down the road after the South Vietnamese mistakenly dropped napalm on her village – were described by Sylvia Shin Huey Chong in her 2012 book The Oriental Obscene: Violence and Racial Fantasies in the Vietnam Era as “exalted icons.” These images were published around the world, and in the U.S., they were credited with helping shift public opinion against the war. But if these images helped establish any visual context, it was one of violence committed by the Other toward the Other. Americans were dying in staggering numbers, but what we saw was violence waged by the Vietnamese against each other. What did it matter if foreigners in places with inscrutable names killed each other, so long as something resembling democracy and capitalism prevailed? Violence visited upon non-white bodies was made palatable, first journalistically and then in popular entertainment. Lê’s work skewers that myopic perception by focusing on what it means to be the disposable Other.

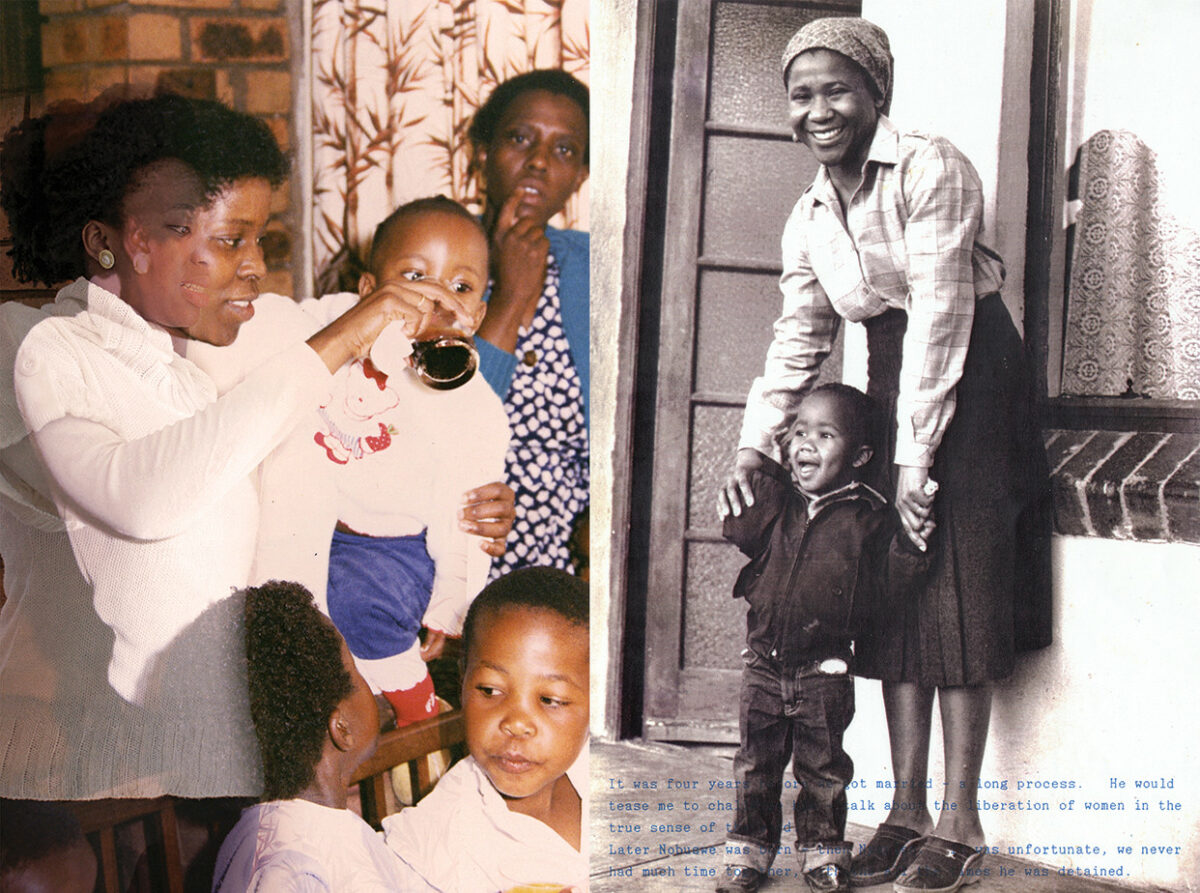

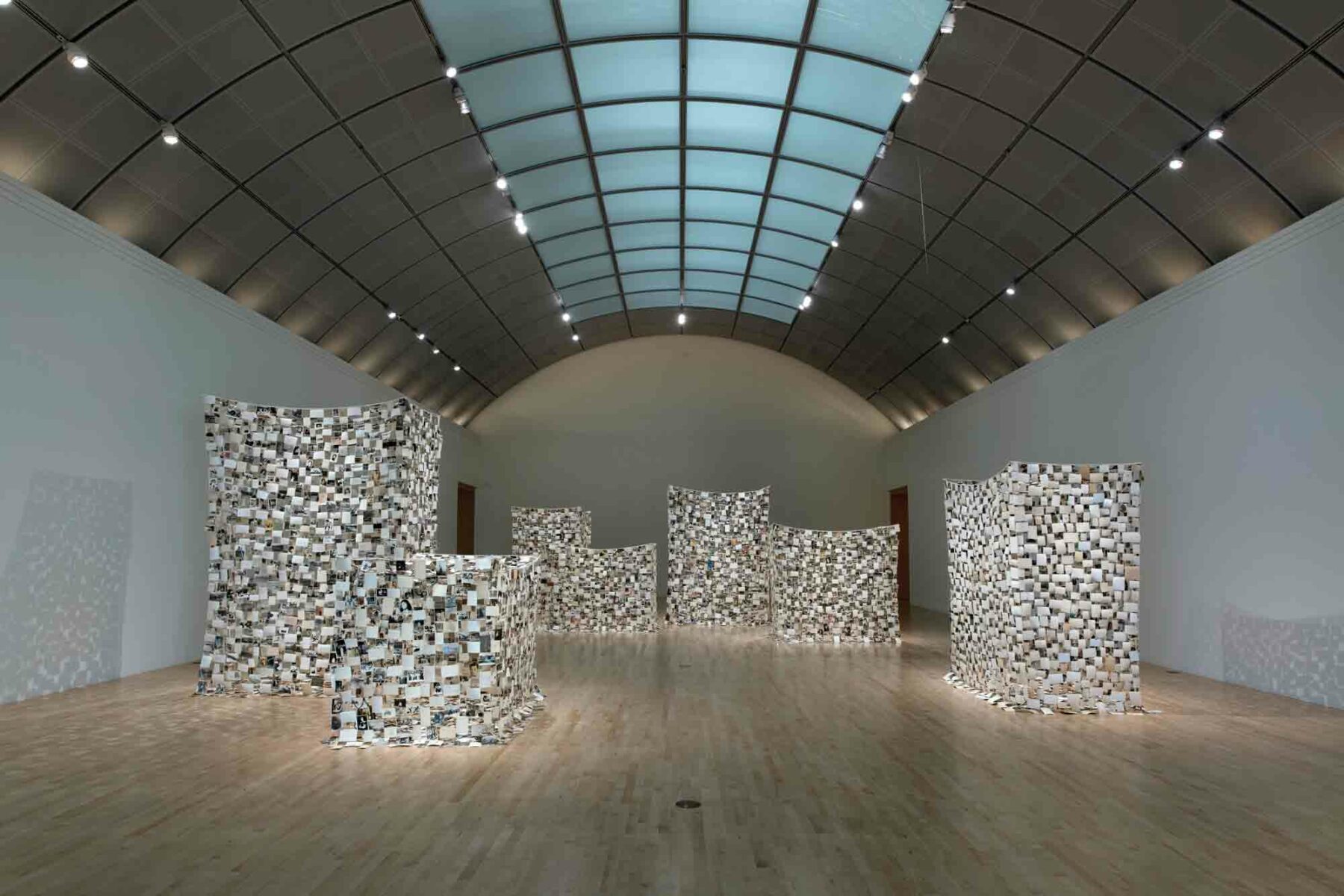

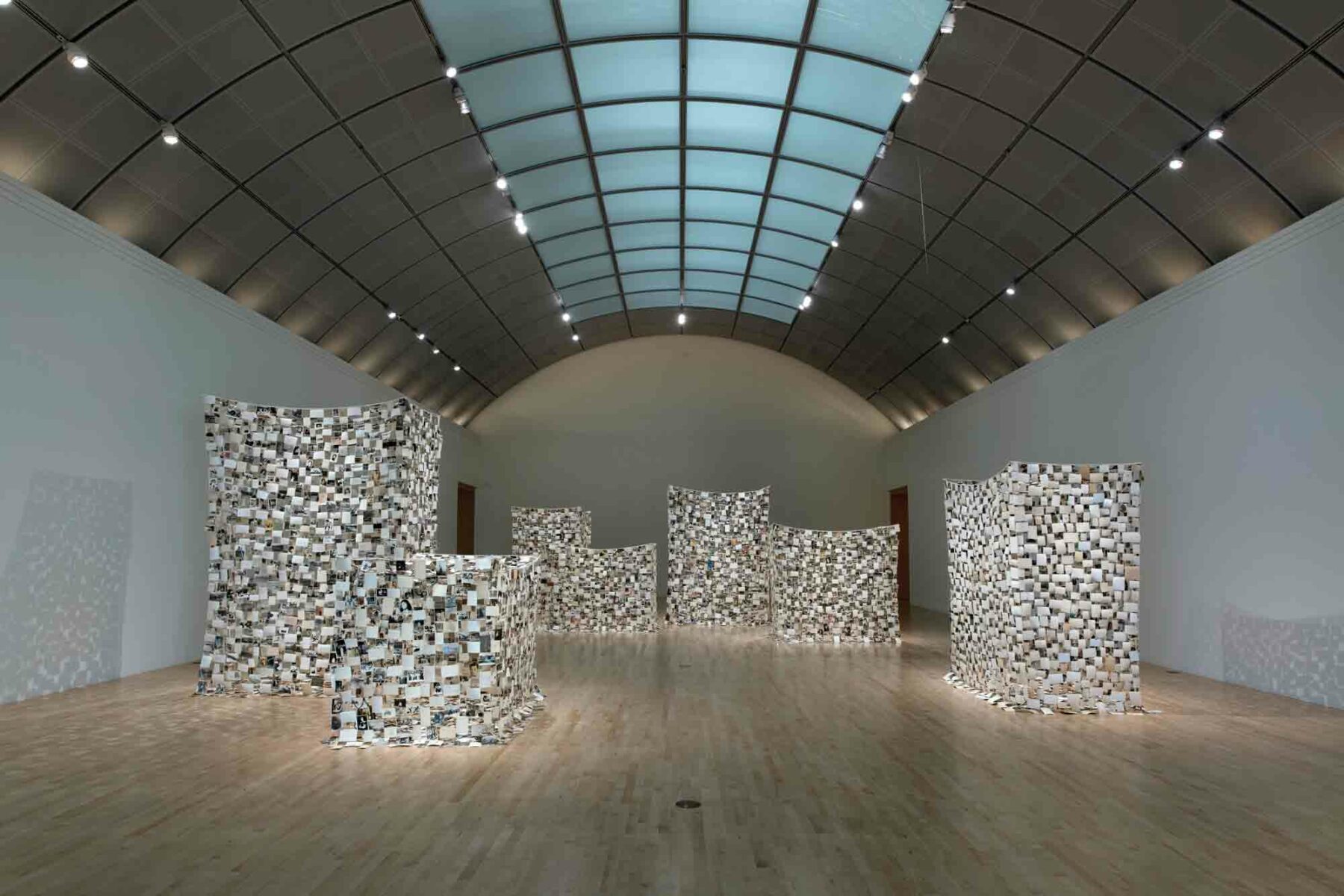

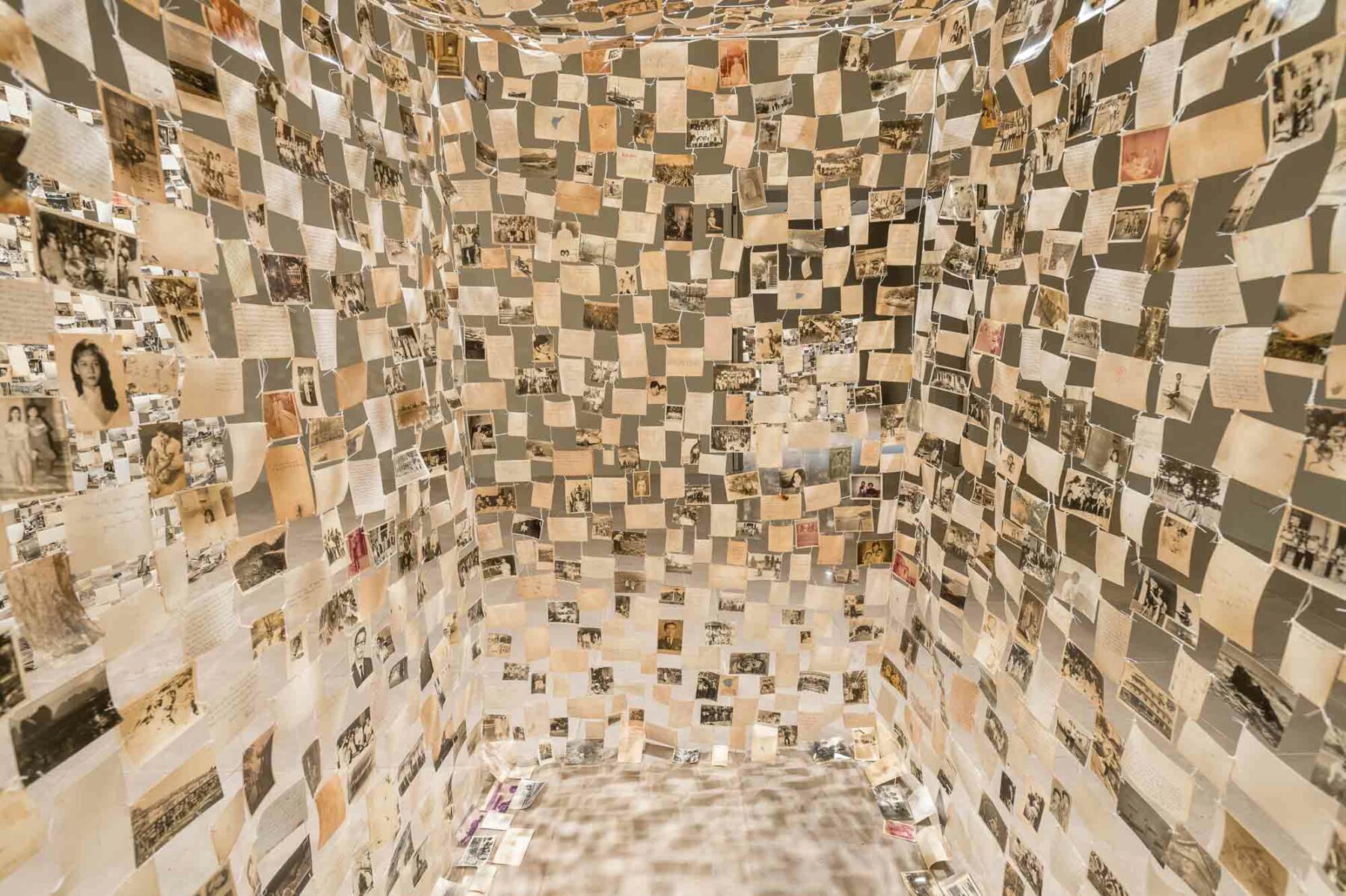

Crossing the Farther Shore (2014), seven photo constructions that gracefully occupy the museum’s main second-floor gallery, anchors the installation. The variably sized armatures, which recall mosquito nets, are made of thousands of interwoven vernacular photographs Lê collected over two decades. The project began as the artist scoured Ho Chi Minh City antique shops hoping to find his own family’s visual artifacts, which were scattered when they fled Vietnam. Though Lê’s search for personal mementos was unfulfilled, the images he collected form a surrogate family portrait that illustrates the profound estrangement that settled into the country as the war dragged on, a point articulated by author Thy Phu in her 2014 article “Diasporic Vietnamese Family Photographs, Orphan Images, and the Art of Recollection,” published in the Trans Asia Photography Review. Phu notes that many South Vietnamese destroyed or dismembered family photo albums before the war’s end. Images highlighting perceived support for the American cause, or “bourgeois” pursuits such as international travel, were violently disavowed. The orphaned, decontextualized images that Lê collected form a metaphorical portrait of a nation’s family divided.

The armatures are built from images that capture moments ranging from the celebratory to the mundane, and those are only the images we can see. One small structure is built entirely from photographs that are turned inward, so the image is unknowable. The photographs scattered on the floor inside the armature are likewise turned face down, reading as substitutes for the war dead whose names linger on the lips of bereaved family members. They were nameless to Americans during the war, and now, by the physical denial of the image, they suffer a second metaphorical death.

Lê’s expansive creative corpus advances the distant and not-so-distant historical context of the Vietnam War, which extends back to the disastrous 19th-century French colonialist project that ended in 1954 and the subsequent Cold War proxy fight for influence waged by the U.S., China, and the USSR. Lê’s work reinforces the idea that the trauma endured by the Vietnamese people did not begin as the United States asserted its unwelcome influence, nor did it end when the U.S. left. It is an old and open wound.

Though Lê’s practice is heavily influenced by photography, his output is broadened by multimedia projects that render Vietnamese voices more present in discussions of the war and its aftermath. Projects included in the current exhibition – the film The Imaginary Country (2006); the installation Light and Belief: Voices and Sketches of Life from the Vietnam War (2012), comprised of a film and 102 watercolor drawings by the artist; and Visions in Darkness: Tran Trung Tin (2015), his film about artist Tran Trung Tin – visualize, respectively, the allure and imperfection of memory, the experiences of artist-soldiers who recorded life at the war’s front lines, and the dangers of government-mandated social realism in art. These projects fill a representational void, particularly for Vietnamese and Vietnamese-American audiences who have long endured western, one-dimensional accounts of the conflict that suggest the only casualties were servicemen who died in-country, or those who returned to the U.S. only to be treated as pariahs who lost a deeply unpopular war.

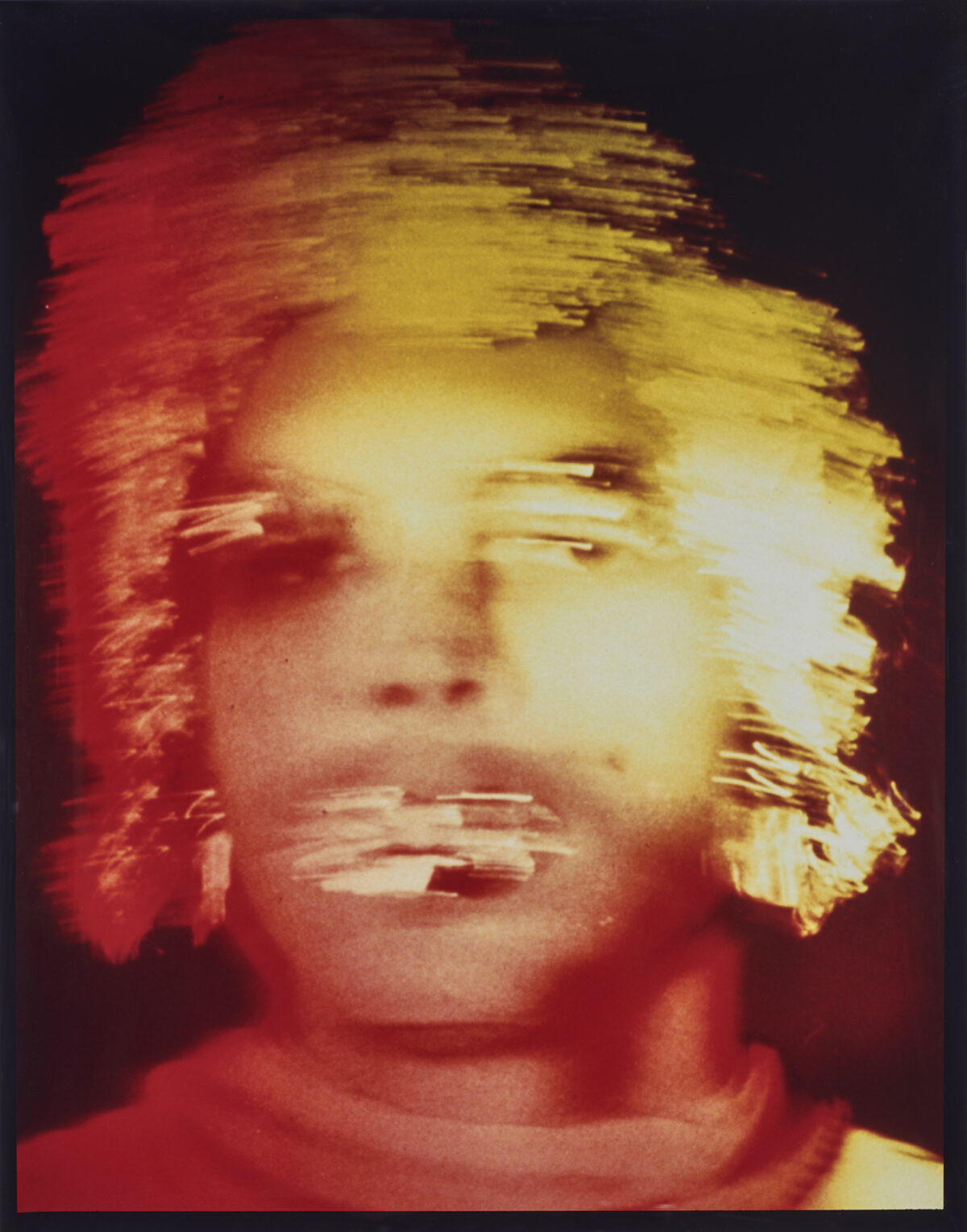

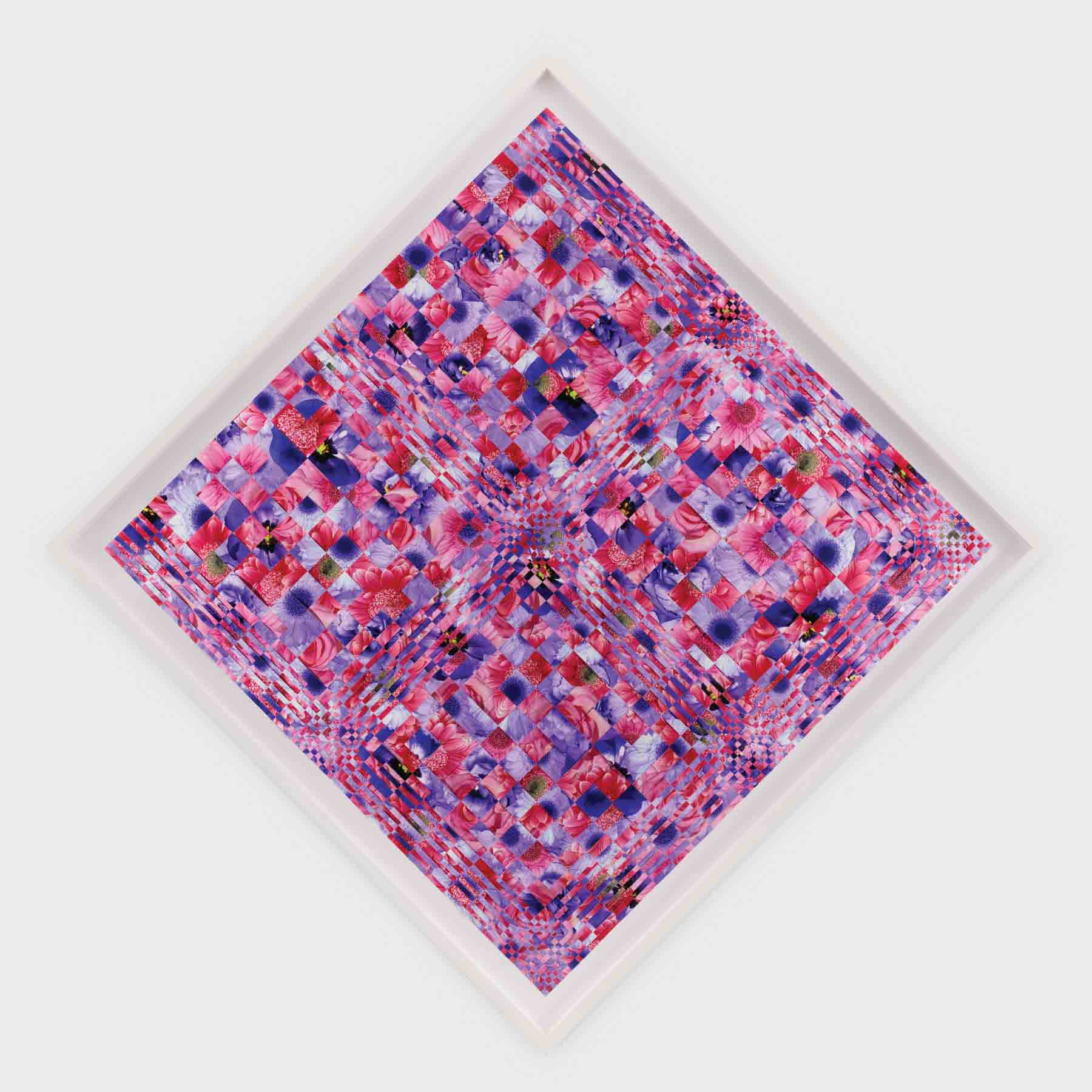

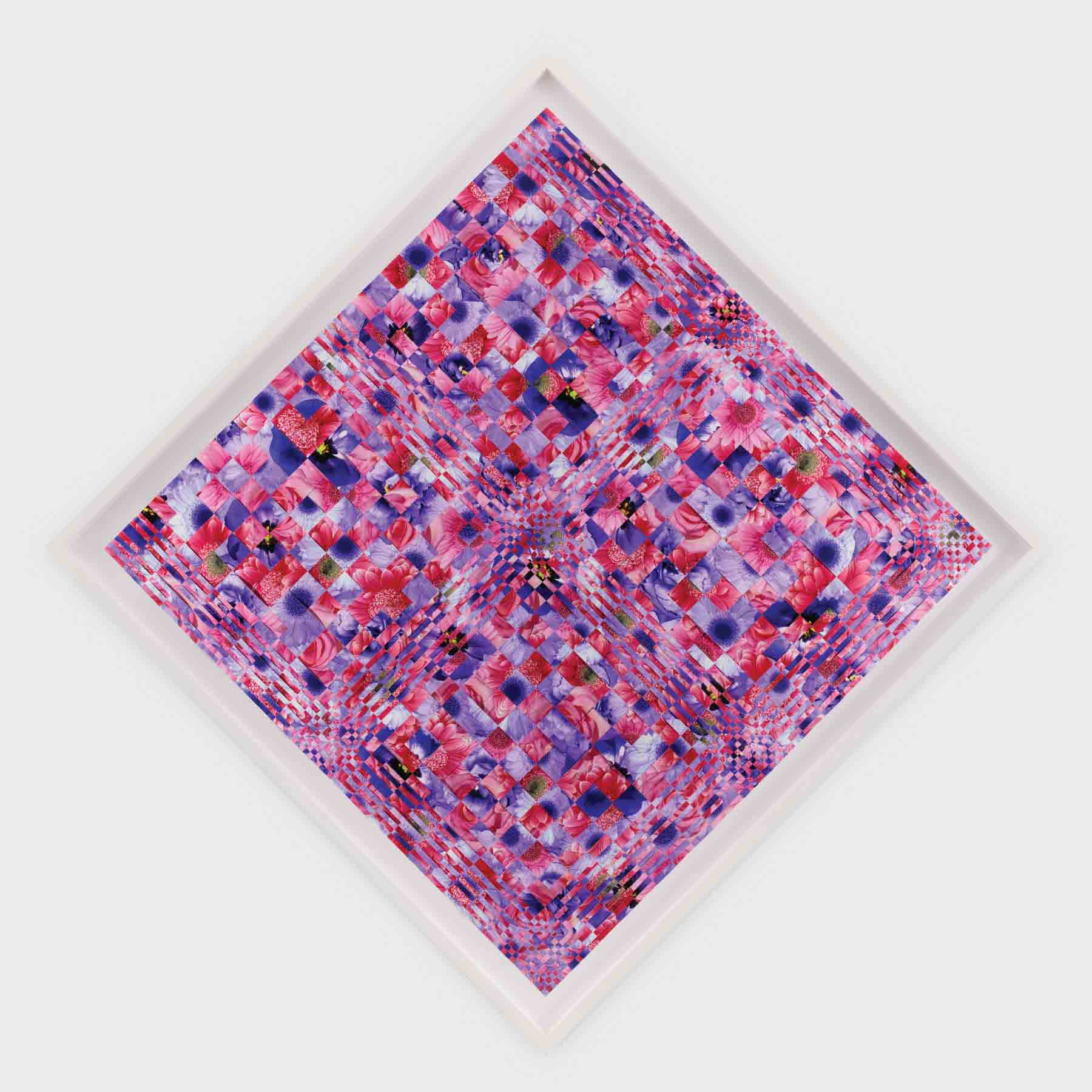

At every turn, True Journey Is Return exposes the trauma inflicted by the war – the physical insult of death and displacement on a mass scale, of course, but also the psychological distress weathered by those who survived, only to face erasure when the American war narrative eclipsed all other experiences. Dinh Q. Lê strives to correct that erasure, and that nascent hope is rendered here in his 2006 Tapestry series. The vibrant, decidedly abstract woven compositions utilize color to represent the rituals that have sustained Vietnamese citizens in the years since the war ended. Photographing in Ho Chi Minh City’s famed flower markets, Lê again cuts each image into slender strips that are then woven diagonally and horizontally. The resulting compositions – dense with pink, purple, orange, and red – often distort the actual flowers and bouquets he captured. Rather, these vibrant mashups are all about the colors that are associated with life, death, and renewal. The radiant red and orange in one of the untitled images mirrors and beautifully undercuts the familiar scenes of fiery destruction that propel Apocalypse Now and subsequent films glorifying American military aggression. It is an explosion of color, not bombs. It is an image that envisions restoration, not destruction.

—Roula Seikaly is an art writer and curator based in Berkeley, CA, and senior editor at Humble Arts Foundation.