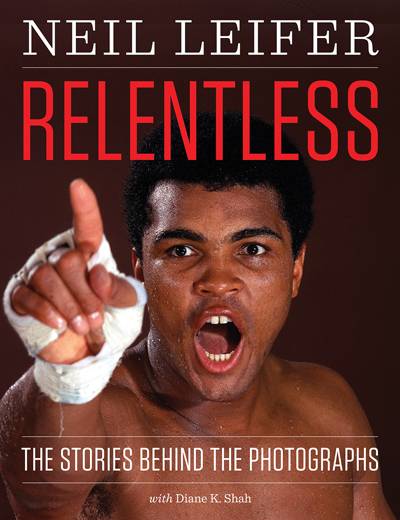

In the micro worlds they create, model-building photographers often seek to revisit their childhoods. David Levinthal never left his. His first project, Hitler Moves East, conceived and executed with the cartoonist and fellow Yale alumnus Garry Trudeau, employed the toy soldiers of his youth to tell a harrowing story of the Russian front in World War II, the kind of story he grew up reading about. It became a cult classic on the order of other 1970s icons, Nancy Rexroth’s Iowa and Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan’s Evidence. Since then, he has used replica figures to explore topics from pornography to race to the war in Iraq. The upcoming exhibition of his work at the George Eastman Museum, titled War, Myth, Desire (June 2- January 1, 2019), is his first retrospective in 20 years. It reveals the photographer as a crypto-historian, exploring the trauma of real events through the faceted lens of memory, allegory, and popular imagery.

Lyle Rexer: Your biography struck me. I see that after Yale and the publication of Hitler Moves East, when you should have been planting an iron wedge in the slightly open door of the art world, you wound up getting an MBA from MIT.

David Levinthal: The short answer is, I encountered a series of frustrations after grad school, including finding a steady teaching job. I said, “I don’t need this.” But there was also in the back of my mind the idea that maybe I had said all I had to say. My brother was an economist, and it wasn’t so strange to think about such a career change. I also discovered I loved marketing, and because my family was on the West Coast, and I had gone to Stanford, I gravitated to the tech industry just as it was blowing up. My starting salary was five times what I would have made at UNLV [University of Nevada, Las Vegas], where I wasn’t rehired. Eventually, I got a partner and started my own PR firm.

LR: And the rest, as they say, is history. No, really, what got you back to making pictures?

DL: Honestly? I started taking photographs again to impress a girl I was going out with or trying to go out with. That didn’t go very far, but when I looked at the pictures, I went, “Wow!” The photographs were good. I hadn’t said all I wanted to say. I was house sitting for my parents in Silicon Valley, and I set up a bridge table in my sister’s bedroom and began to make set-ups again. Later I rented a space in San Carlos with no windows. It was perfect for me. I would take stuff with me and work on business trips. I showed work to some curators and they encouraged me, and at one point Garry Trudeau said, “You have to get out of there.” So I sold my half of the business and moved to New York.

LR: I’ve talked to a number of artists who work with models, and one of the things they have in common, both men and women, is a love of working with their hands, of making the set-ups in miniature and seeing what they look like, peering at them.

DL: When I was at Yale, I felt I had to do something valuable with my time, rather than street photography or trying to make the perfect image of a glass of beer. But I never liked the studio. I had this idea of making a series of photos of unwrapping toy soldiers from a box and setting them up – the entire sequence. But once they were out of the box, I got excited. I started building block cities and doing more set ups. I learned the depth of field advantages of a Rollei with a bellows. I tried to make a photograph of a burning bridge.

LR: There was fire.

DL: There was definitely fire. I wound up melting my mom’s linoleum floor. But as she said, “I never liked that floor anyway.” I basically went off into this alternative world and just kept adding more and different elements.

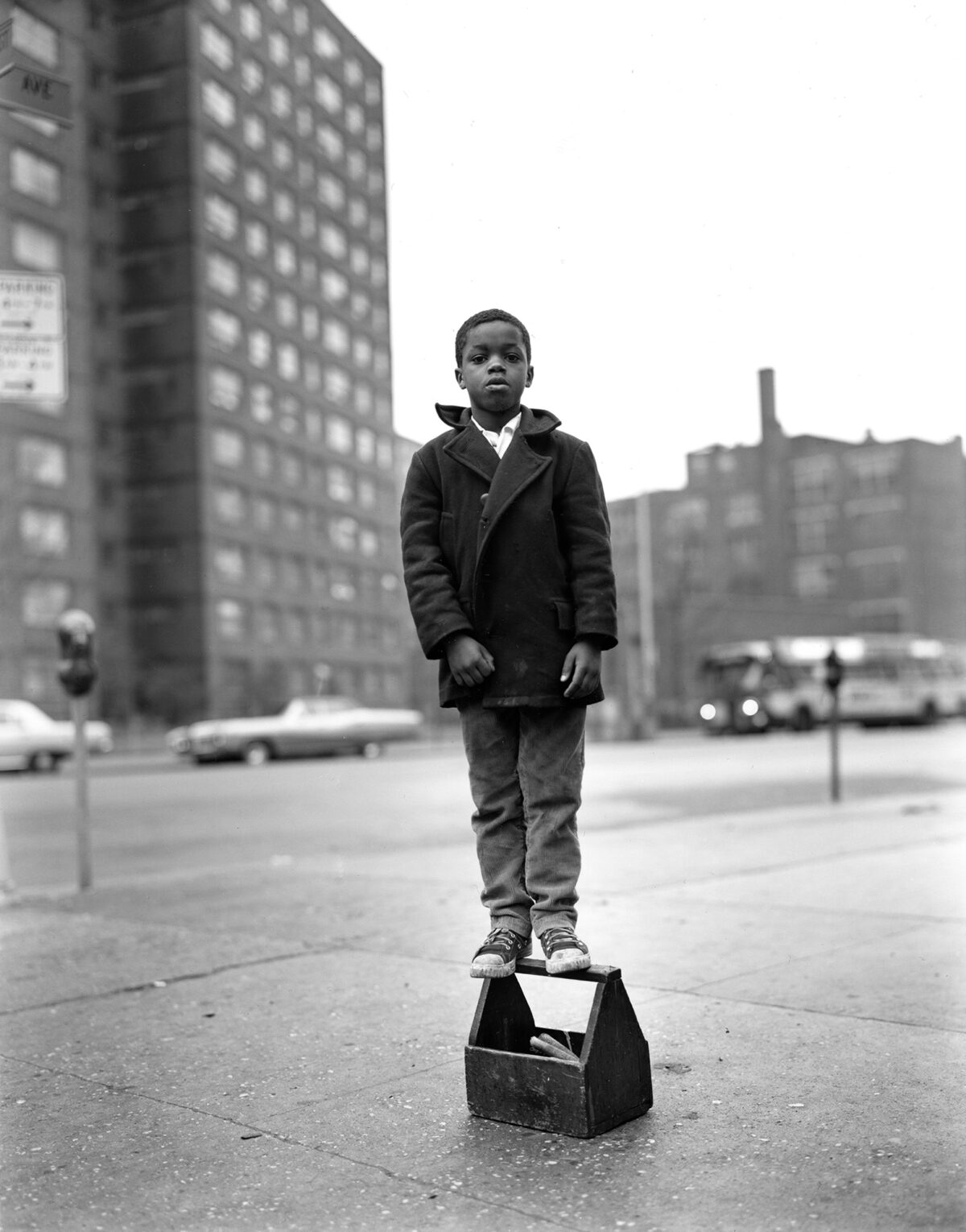

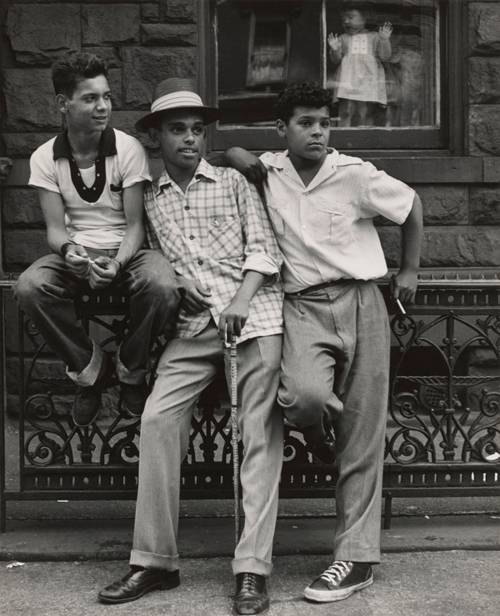

LR: You don’t appear to adopt a consistent attitude or treatment with your various subjects. Some are more “realistic” or even deceptive vis-à-vis the camera, and some are more explicit about the commercial character of the figures – Blackface, for example.

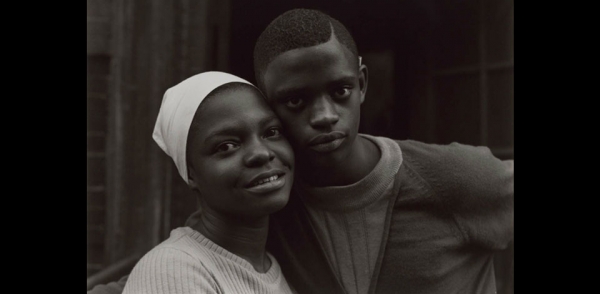

DL: It may have something to do with how the project came about. After a conversation with Bill Christenberry, I had this idea to do a series based on the film Birth of a Nation. When I went looking for African-American figurines, I was astounded by what I found, and I decided just to focus on the memorabilia. The Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in Philadelphia was interested in doing a show but backed out when the curator and a board member saw how the work was developing.

LR: They were afraid of pushback?

DL: I never got an explanation, but when the work was later published as a book, it got the attention of Spike Lee. He used some images in Bamboozled [2000], and when the series was shown [in 2001] at Conner Contemporary in Washington, D.C., coincidentally during the NBA all-star game, a lot of very tall people came into the gallery saying, “Spike told us we had to come see David’s show.” And after the ICA show was cancelled, I wound up at a symposium [Change the Joke and Slip the Yoke: A Harvard University Conference on Racist Imagery, 1998] at Harvard sitting next to [Civil Rights activist] Julian Bond.

LR: Could you have predicted any of the outcomes, positive or negative?

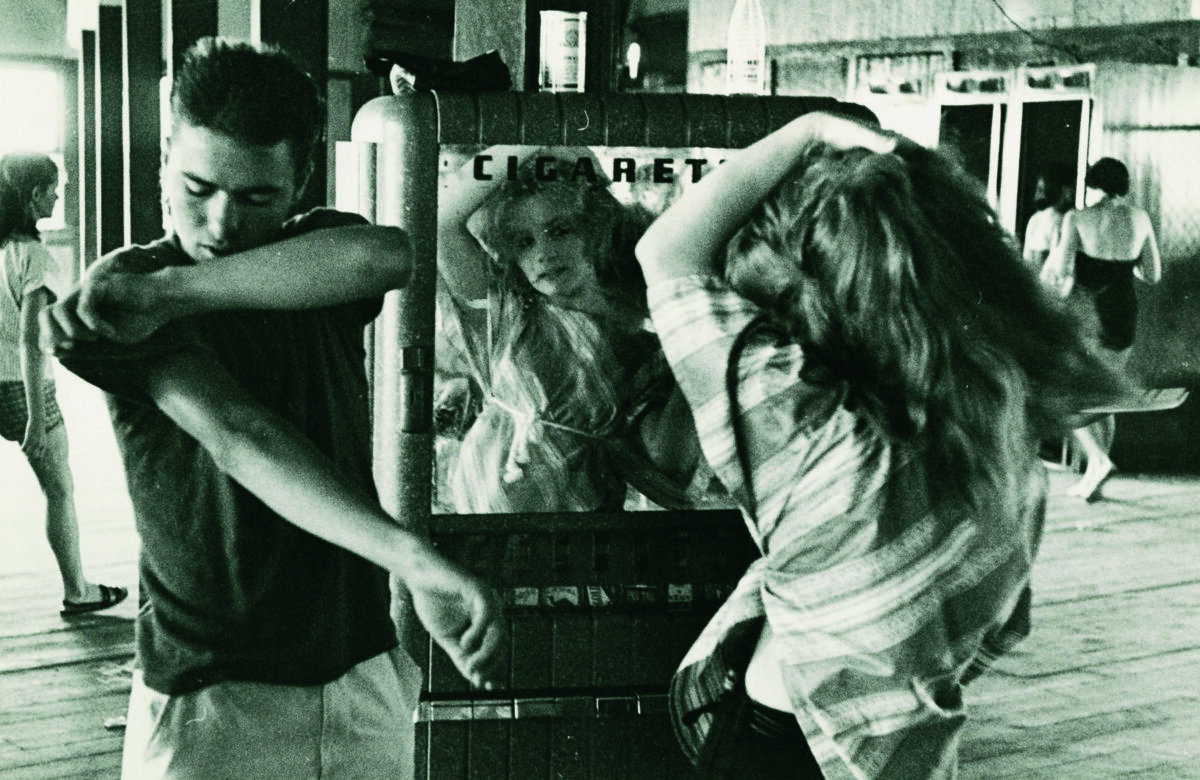

DL: I suppose I was naïve, and I was caught up in the material. I work more intuitively, and I don’t overthink the conceptual aspects. I’m not after that consistency. I play at the boundary of fantasy and reality, and that boundary shifts. I am more of a problem solver. I usually have a picture in my head about how I want an image to look, and it is often an image from memory based on something I’ve seen in a movie – by John Ford, say, or Francis Ford Coppola. In terms of my evolution, I would say that I have gotten better at understanding how to realize an image in my head, what I need to do that.

LR: Almost like you have become more of a photographer, less of a tinkerer.

DL: I am not so sure about that. I still set things up. I even grew grass to get the effect of a Russian wheat field. But moving from Polaroid film to digital after the Polaroid studio closed in 2007 was a true game changer. When I first had the idea to do a series on the Iraq war (I.E.D.), Garry Trudeau insisted I had to shoot it digitally. It was the first digital war. Of course I could see what I was doing in real time and make many more adjustments to the images while I worked. But maybe even more important, I could expand the scale of what I printed. Since I visited the Louvre when I was 13, I have been fascinated by history painting, those giant canvases that tell a near mythologized version of the past, like Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People. Even though I am working on a small scale, I can think about making my own history paintings. I can travel anywhere in time. You can see this in the show at George Eastman Museum and in an earlier show of my work there in 2015, History.

LR: These prints are also closer to the scale of cinema.

DL: Everything in my work is filtered through films, photographs, and memory.

On the occasion of his retrospective at the George Eastman Museum, from June 2 through January 1, 2019, David Levinthal speaks to contributor Lyle Rexer about incorporating memory, allegory, and popular imagery into his photographs based on the various micro-worlds he’s created over the years, in series from Hitler Moves Eastto Historyor Blackface.