Behind Mickalene Thomas’s well-known bedazzled paintings of Black women in heavily patterned, retro interiors, there is always a photograph. The artist stages the scenes in her studio with friends and family and takes photos and videos that then become source material and often artworks in their own right. In two exhibitions by Thomas concurrently on view, the artist draws on others’ images for inspiration and subject matter. The shows couldn’t look more different – one features her own work and the other is a historical exhibition she co-curated – yet both grapple with issues of representation, ownership, and agency.

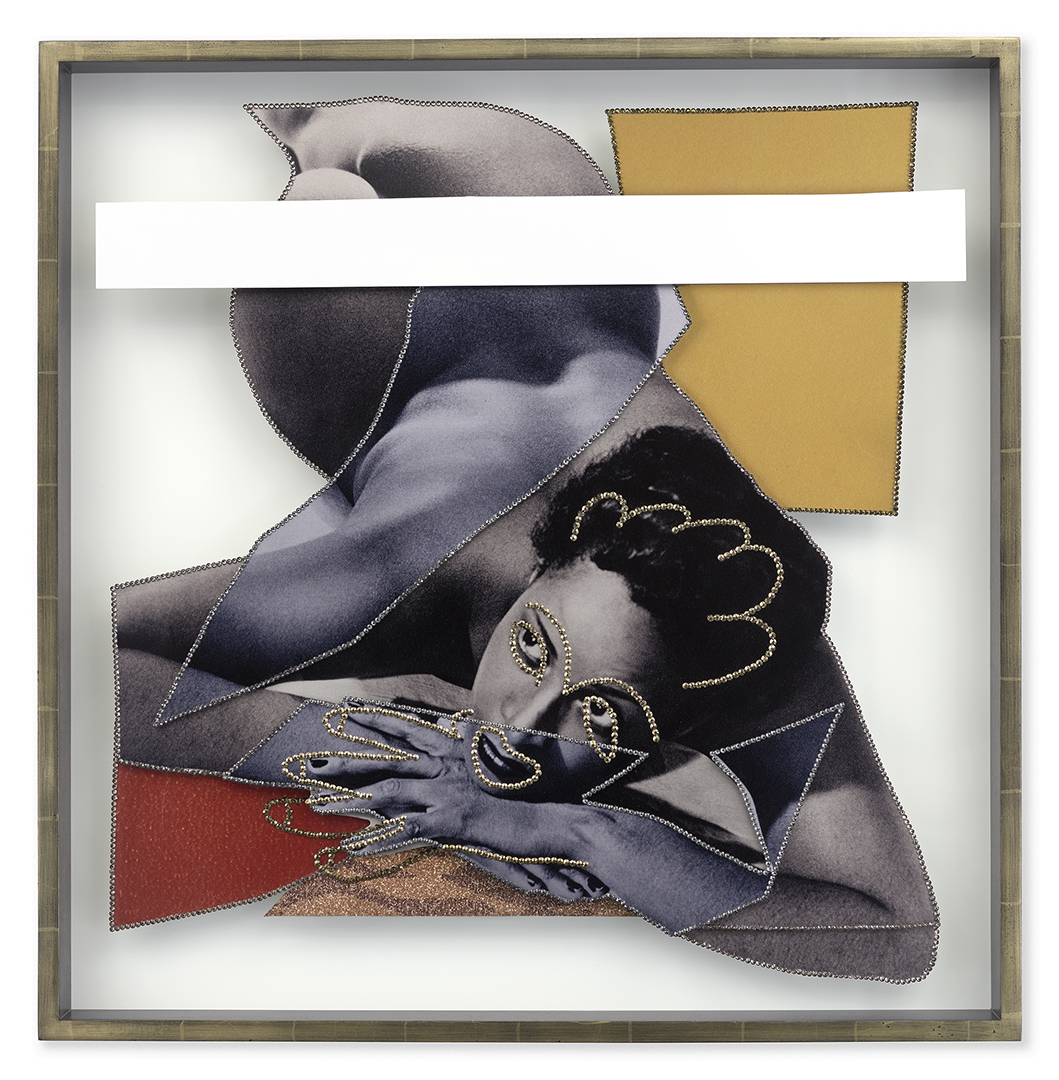

In je t’adore at Yancey Richardson through November 11, Thomas presents works from her ongoing series based on Black erotica from 1970s Jet magazine centerfolds and calendars, as well as nudes from the 1950s French publication Nus Exotique. The interior settings of her early works were recognizable spaces, such as living rooms, but the women in the 13 photo-collages here are set apart from their surroundings, floating amid isolated abstract elements. Sometimes the women themselves are fractured, Cubist-like, and sometimes the whole figure is cut out from the image. The pieces are then reconfigured and reconstructed in layers and suspended within a frame, adding actual depth and shadows to the compositions.

The works are embellished in Thomas’s signature style. Contours and curves are enhanced with rhinestones and glitter. Colorful lines trace parts of the women’s bodies, like graffiti on a subway ad. Breasts and buttocks are comically highlighted; looping lines create curlicue necklaces or flowery wallpaper. It’s hard to see these works as anything other than a celebration of Black women’s bodies. But why did Jet, a weekly news and culture magazine, even publish nudes? Some observers at the time believed that the “beauty of the week” feature helped to mainstream Black women’s bodies and challenge white beauty standards. Others were concerned about objectifying the Black body in the process of making Black beauty more visible. Whether the women felt empowered or exploited – Thomas contends it’s the former – they were posing, more or less, on their own terms for a Black audience. When considered in the context of Thomas’s works that wrest Western tropes of odalisques and nudes away from the “male gaze” and reframe them for the Black gaze and female gaze (three of her Courbet-inspired photos are on view at Yale), it’s easier to see these women as fearless and in charge.

One of Thomas’s enduring influences is the 2002 book The Black Female Body: A Photographic History by Deborah Willis and Carla Williams, which considers Western culture’s fascination with the Black body. Among their observations is that, in the 19th century, Black women weren’t photographed as art subjects or as individuals so much as anthropological specimens – often naked, dehumanized, and not identified beyond a “type.”

The book also informs some of the thinking behind Mickalene Thomas: Portrait of an Unlikely Space at Yale University Art Gallery through January 7, 2024 (Willis contributed an essay to the show’s catalogue). Keely Orgeman, Yale’s Seymour H. Knox, Jr., Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, had met with artist Titus Kaphar, whose studio is in New Haven, to discuss a 19th-century portrait miniature in watercolor on ivory of a freed Black woman named Rose Prentice that Yale acquired in 2016. Kaphar was enthusiastic about the prospect of an exhibition and suggested Orgeman meet with Thomas, a Yale alumna (MFA 2002). That meeting evolved into this collaborative exhibition, which contextualizes the unusual portrait. Orgeman and Thomas set out to explore Black portraiture in the pre-Emancipation era, supplementing the Prentice portrait with daguerreotypes, portrait miniatures, printed illustrations, and silhouettes. The curators’ intention was to knit together a narrative of sorts by finding “points of connection” among the various subjects, some of whom remain unknown, “with the aim of building a collective portrayal of Black private life that animates the individual,” as Thomas writes in the catalogue.

The show’s ambition is big, but the works are mostly tiny, which makes for a sparse installation and a lot of close-up viewing. The galleries’ walls are painted a dark blueish gray, nearly black, that Thomas says is intended to evoke Black skin. Many of the works are displayed in dimly lit wall niches behind glass, which makes them seem to float in the darkness. Here and there, wall-mounted black shelves or fireplace mantels hold domestic objects, such as books and vases, painted black. The overall result is, unsurprisingly, dark, but the metaphors come easily: the darkness of memory, of history, of slavery, and feelings of solemnity and oppression.

At five points in the exhibition, Thomas has staged spare domestic scenes, each of which contains, among other things, a wing chair, a table, and a wall-hung photograph by Thomas of the interior of the Tucker house, where Prentice worked for the Tucker family and, without viable options, continued to live as a domestic servant after her manumission. Most portraits of Black people were commissioned by and for their white owners; Prentice’s was made by a well-known portraitist for the adult daughter of the Tucker family, whom she helped raise. Enslaved individuals could request to have their portrait made, albeit with the permission of their owners. The slave trade tore apart Black families, and the portraits, a rare privilege, provided a way for them to at least remember their loved ones. The opportunity also provided the sitters a sense of self-possession. Observing the sitters’ styles of dress, jewelry, and head wraps, Willis writes in the catalogue: “What is common among most of these family treasures is the notion of free Blacks being seen as they desired to be seen.”

Thomas often includes works by other contemporary artists in her exhibitions, and she does so at Yale as well. In keeping with the miniature theme, Curtis Talwst Santiago makes tiny dioramas in silver Edwardian jewelry boxes. The two included here are of people “chilling with some friends” in a living room and “chilling by the pool,” according to the descriptive titles. The more poignant examples include Betye Saar’s boxed assemblage from 1975 that takes on the Black caregiver stereotype. On the left side is a drawing of a Black woman with her own child in her lap, and on the right an Aunt Jemima figurine holds a wooden spoon in one hand and a grenade in the other. Behind her, the box is lined with a sales document that describes an enslaved woman’s skills and mentions that she has had four children, from whom she was presumably being separated.

But it’s the work of Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter that really nails it. Easily mistaken for daguerreotypes, the three photographs by the Philadelphia artist are printed on metallic paper and displayed in hinged metal boxes like many of the historical keepsakes nearby. Two of the images are based on nude photographs taken by Thomas Eakins of a suggestively posed young Black girl. He took many photographs as research for his paintings, he claimed, but was a known pedophile and sexual predator. Baxter inserted herself into the images as a protector, shielding the girl with a blanket in one photograph and wrapping her arms around her in the other. The third work is a portrait of the artist at about the same age as the girl in the Eakins photos, so it becomes even more unnerving to learn that the artist was a victim of sexual abuse as a child. In this jarring revelation near the end of the exhibition, Baxter symbolically takes back ownership of the girl’s likeness and dignity, a gesture that this entire exhibition attempts to do for all its subjects.