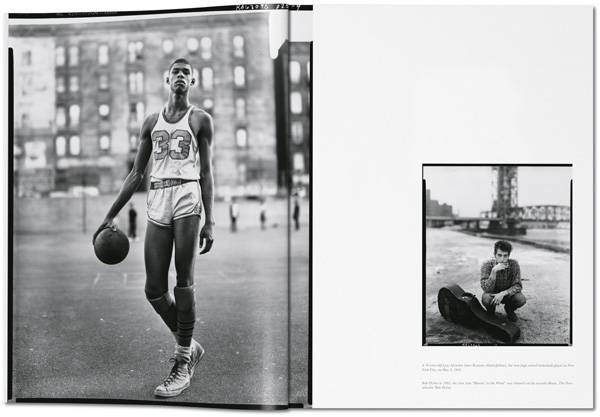

From the beginning, Richard Avedon staked his claim well beyond fashion; his passionate, wide-ranging interests – in theater, dance, performance, politics, and the arts – drew him into portraiture, and portraiture gave him material for his first books. He published Observations, designed by Alexey Brodovitch and with a text by Truman Capote, in 1959. Nothing Personal, a collaboration with James Baldwin, came out five years later and has just been reissued by Taschen, its original Marvin Israel design accompanied in a slipcase by a booklet of previously unpublished material and a new essay by Hilton Als. Of the two books, Nothing Personal is the more ambitious and more socially engaged one, but it’s also more scattered, more anxious, and, inevitably perhaps, less resolved. Celebrity and its warping effect continue to absorb Avedon, but that’s balanced by other, more pressing, concerns: civil rights, black power, an irrepressible counterculture, a resurgent right wing. So Marilyn Monroe, Malcom X, Fabian, and George Wallace all share space here, and a naked Allen Ginsberg faces off across the page with uniformed members of the American Nazi Party. Als reflects on this in an essay that, like Baldwin’s, is more personal than polemical, beginning with his memory of discovering Nothing Personal in the library when he was 13. “In their book,” he writes, “Avedon and Baldwin gave politics a face, a language I could grasp.” But returning to the book again and again, Als realized that it’s also “riddled with the question of identity – what makes a self? – a question that gave a certain 13-year-old ideas about the questions he might ask in this world: Who are we? To each other? And why?” The original book ends in a wrenching crescendo of hopelessness and hope. The new addendum folds the Als text, “The Way We Live Now,” into a portfolio of variants and outtakes (Dylan, Auden, and Mamie Eisenhower did not make the cut), correspondence and contact sheets, and pages from one of the book’s rough maquettes. All not just valuable but incredibly timely. How can we have come so far and still be in the same place?

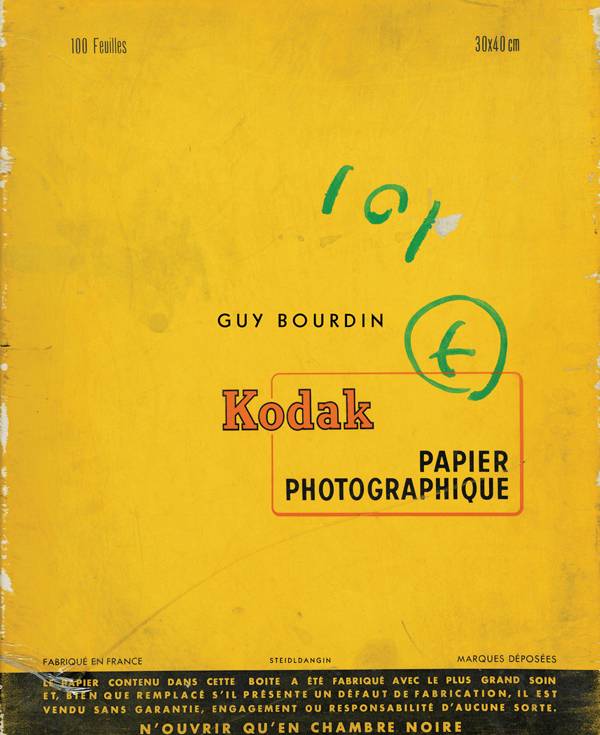

Guy Bourdin’s considerable reputation rests on the super-saturated, slyly provocative, and wildly influential color work he made for French Vogue from the 1960s until shortly before his death in 1991. Untouched (Steidl/ Dangin), a superbly designed book of recently rediscovered black-and-white pictures made between 1949 and 1955, is the first to delve into Bourdin’s formative years, and it’s fascinating. In his essay, Philippe Garner compares the material, including layouts for a planned exhibition, to an artist’s first sketchbooks, used for “testing himself in the world, finding his place, his identity, his point of view.” Young Bourdin (21 in 1949) is a street photographer, a keen observer of the passing scene with a fine sense of composition; he could have turned into Saul Leiter or Dave Heath. The only indications of the outrages to come crop up late, in fashion work that swerves abruptly into the surreal. But photographing a model with flies on her face or a row of flayed rabbits hanging behind her is entry-level audacity, and it’s the least interesting thing young Bourdin has to offer. The pictures that come before that have a restless, searching moodiness that anticipates Antonioni but isn’t about ennui. Bourdin is not world-weary; he’s too unsure of his footing to dominate any place. So he meets it not quite humbly but head-on, alert and alive. And he brings back some quiet, touching images of people and places, especially children, that give him the confidence to go on.