As the Academy Awards approached in early March, many in the art world and beyond buzzed about All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, photographer Nan Goldin’s film with director Laura Poitras, which earned a documentary film nomination. The documentary addresses Goldin’s passionate volunteer work as founder of the advocacy organization P.A.I.N (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) and delves into the artist’s five decades of diaristic visual practice and the terrors of substance-abuse disorder. Memory Lost dug further into those experiences, conveying Goldin’s acute understanding of beauty and horror as elemental to the human condition.

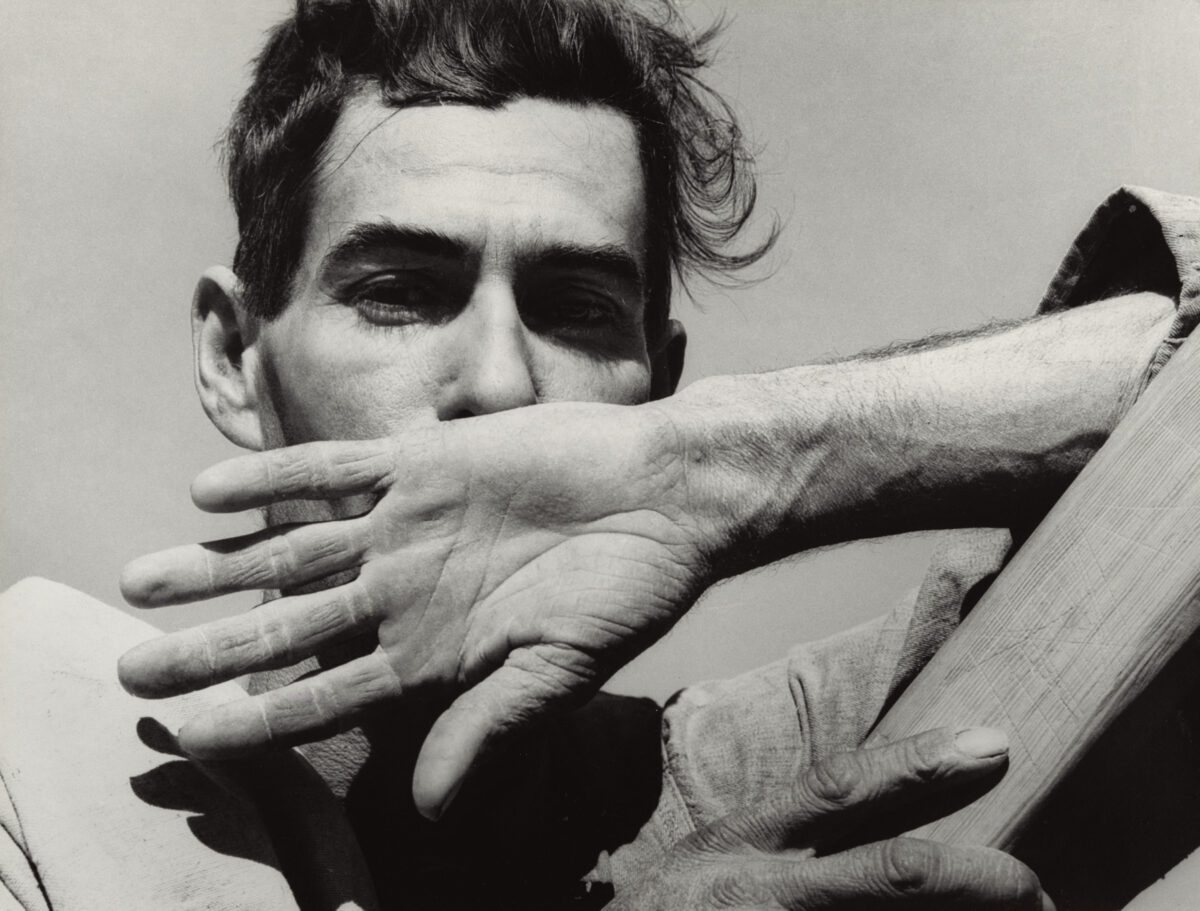

Memory Lost, the titular 24-minute digital slideshow screened in a purpose-adapted media room, begins and ends with archival images of Goldin’s intimates. All young and beautiful and knowing it, they lived on their own often-dangerous terms, rejecting conformist social mores. Too many would fall to either addiction or HIV/AIDS, or both, among several plagues to which Goldin has stood witness.

Replacing the indelible slide carousel and musical score that accompanies The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, Mica Levi, Soundwalk Collective, and Franz Schubert’s narcotic score for Memory Lost is occasionally punctured by archival recordings and new interviews. Urgent voicemail entreaties left for Goldin – “are you awake?” – become part of the soundtrack, the harrowing underlying question being: “are you alive?” The vocal interjections could represent conversations between those struggling with addiction, or trying desperately to stay clean. Particularly chilling in the wide-ranging sequence are images of livestock marked with spray-painted numbers – for sale, or slaughter. The images evoke ghastly metaphorical links between the hapless animals and those grappling with substance-abuse disorder who are sacrificed to rapacious pharmaceutical conglomerates.

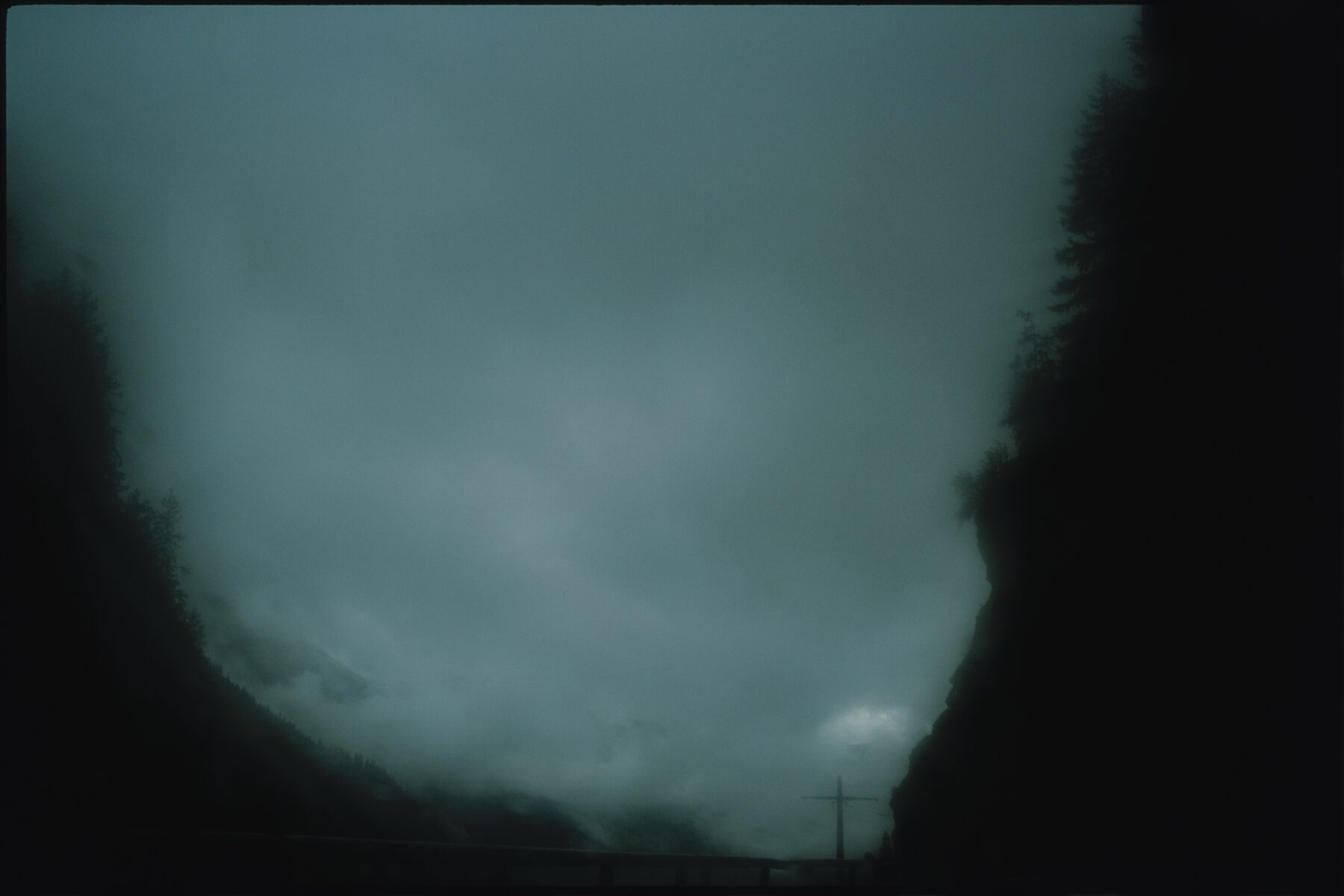

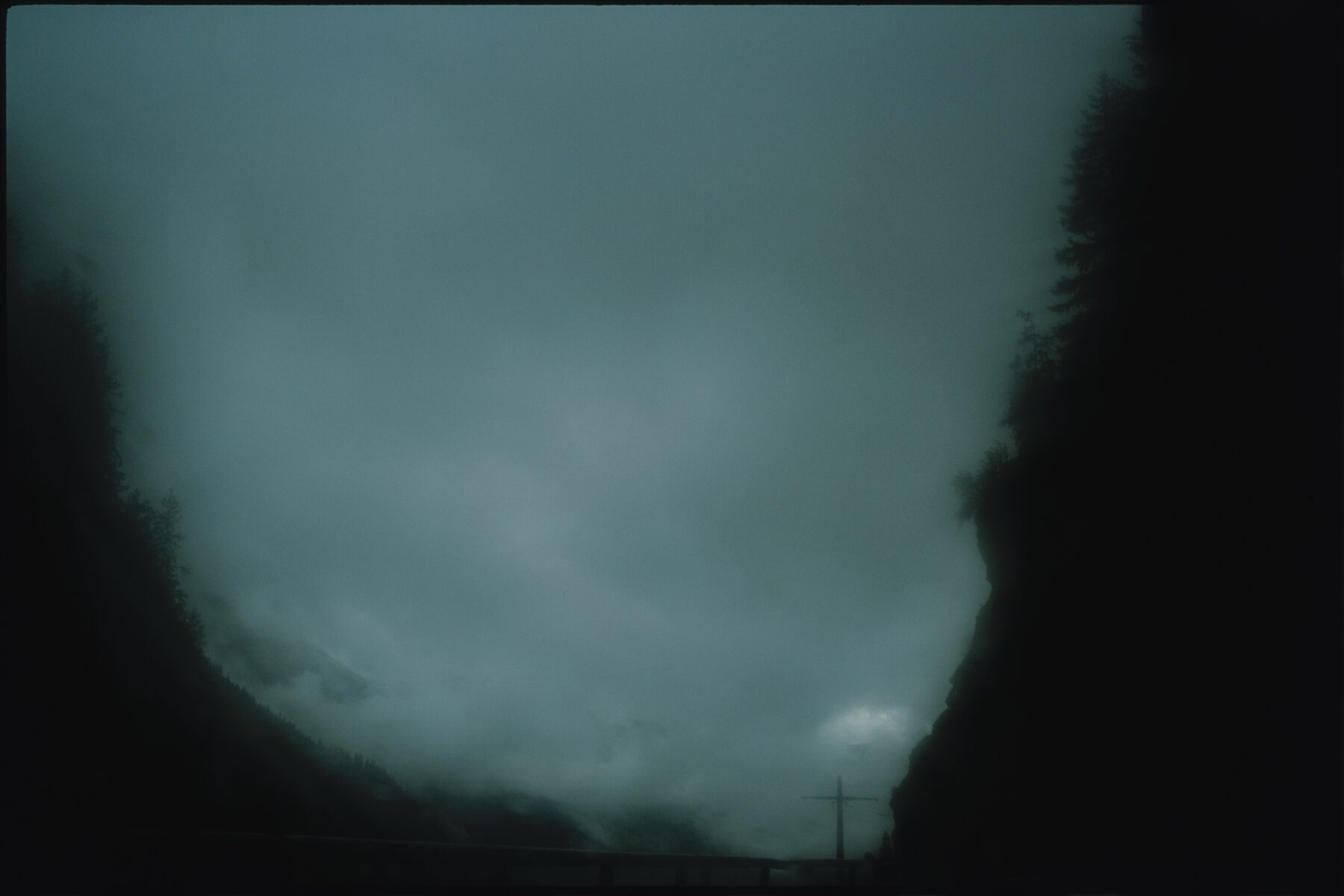

Stepping out of the media room may be a relief. It was for me. While it’s a privilege to view Goldin’s photographs, it also feels uncomfortably voyeuristic to watch her and her cohort waste away as scoring and ingesting intoxicants became more important than shelter and personal safety. The framed images in the main gallery ushered me back to the slideshow more than once, though. Blurred compositions, including Falling buildings, Rome (2004) and Cross in the fog (2002), suggest the psychological and physical struggle born of waking from one nightmare – addiction – only to face another one, the struggle to get and stay clean.

Neither context nor explanation for these images are found in the gallery presentation or the slideshow. Goldin’s search for meaning in her own archive through rigorous editing and recontextualization only reveals more confounding questions about survival, perhaps survivor’s guilt, and what we do with these brief lives of ours. Hung in the smaller gallery, Goldin’s portraits of writer Thora Siemsen spur… optimism. After Siemsen interviewed Goldin in late 2019 on the rerelease of the photographer’s book The Other Side (1993), the author and Goldin agreed to quarantine together as COVID lockdown loomed in early 2020. Siemsen is evidently comfortable with Goldin, who frames the writer with the love she felt when photographing 1970s Manhattan demimonde legends. But these portraits are different. The capture is sharper, even sober, yet with a gentle focus on a trans woman coming into her body. It’s a hopeful look at friendship, and what may come next in Goldin’s extraordinary life.