When the political world turns dark, paranoid fantasies abound, which is why Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan’s Evidence (1977), a textless book of carefully organized found photographs suggesting vast impersonal forces controlling our lives, never seems to go out of style. Mandel and Sultan went on to have very different careers, and both are on display at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Sultan’s retrospective (Here and Home, April 15 – July 23) is paired with Mandel’s vision of the 1970s (Good 70s, May 20 – August 20), that period when the two got together to plot California’s takeover of the photographic world. A New York exhibition of Mandel’s work is at Robert Mann Gallery May 11 through June 30.

Lyle Rexer: The Good 70s?

Mike Mandel: It really was, and San Francisco is the only place that makes sense for the show. San Francisco was the genesis of my creative life. It revolved around the San Francisco Art Institute, where I met Larry Sultan, and that period when photography was becoming a full-fledged member of the art world. It was also a time when I was free to devote myself just to pursuing the ideas I had. If you can get a state education for $47 a semester, that gives you a lot of economic freedom.

LR: But you weren’t from San Francisco.

MM: No, and neither was Larry. We both had this Los Angeles attitude toward San Francisco, which was that the city was all about the residual image of the Beat Generation, with people sitting around cafes smoking cigarettes and looking cool and detached. We had watched the California landscape change rapidly, and we wanted to oppose that intellectual heaviness, shake up that artiness. Both of us, in different ways, had been focused on billboards and the language of advertising, so we decided to do a billboard project. We contacted a billboard company, which gave us a billboard in Emeryville, a semi-industrial part of the city. We did a 10×22-foot photographic billboard that basically showed the view just across the street, and a worker being lifted out of this environment by a balloon that we painted in. When we did an “opening” for it, people from the community told us how much they liked it. This became an important lesson for me, that audiences don’t have to be inside museums, they can be in neighborhoods. Our next billboard was a sendup of the tautological, didactic, redundant language of advertising: three images of a woman rising out of a giant cornucopia, with oranges. Gradually the oranges lose their color and become black and white, while the woman gains color and becomes a sort of movie star. It was a way of commenting on how farming was yielding to the entertainment industry. Three days later, the billboard was “accidentally” covered by an advertisement for Sunkist oranges. Coincidence? We didn’t think so, so we threatened legal action, and the next thing you know we got 10 free billboards. Our photo Oranges On Fire (1975) went up in San Francisco, Oakland, Santa Cruz, and Emeryville. The whole point was to decontextualize the billboard, to get people to stop for just a moment and puzzle over what they usually take for granted.

LR: There was a lot of healthy mental activity between you and Sultan.

MM: In some ways, we were an ideal combination. Larry’s hard drive of a brain seemed to be completely accessible to him at all times, and his arguments would come out logical, coherent, and completely formed, whereas I was not that way at all. When we were putting together Evidence, and I felt he was trying to push an idea too hard, I would say things like: “You’re doing it again, you’re acting like your father and trying to be a salesman.”

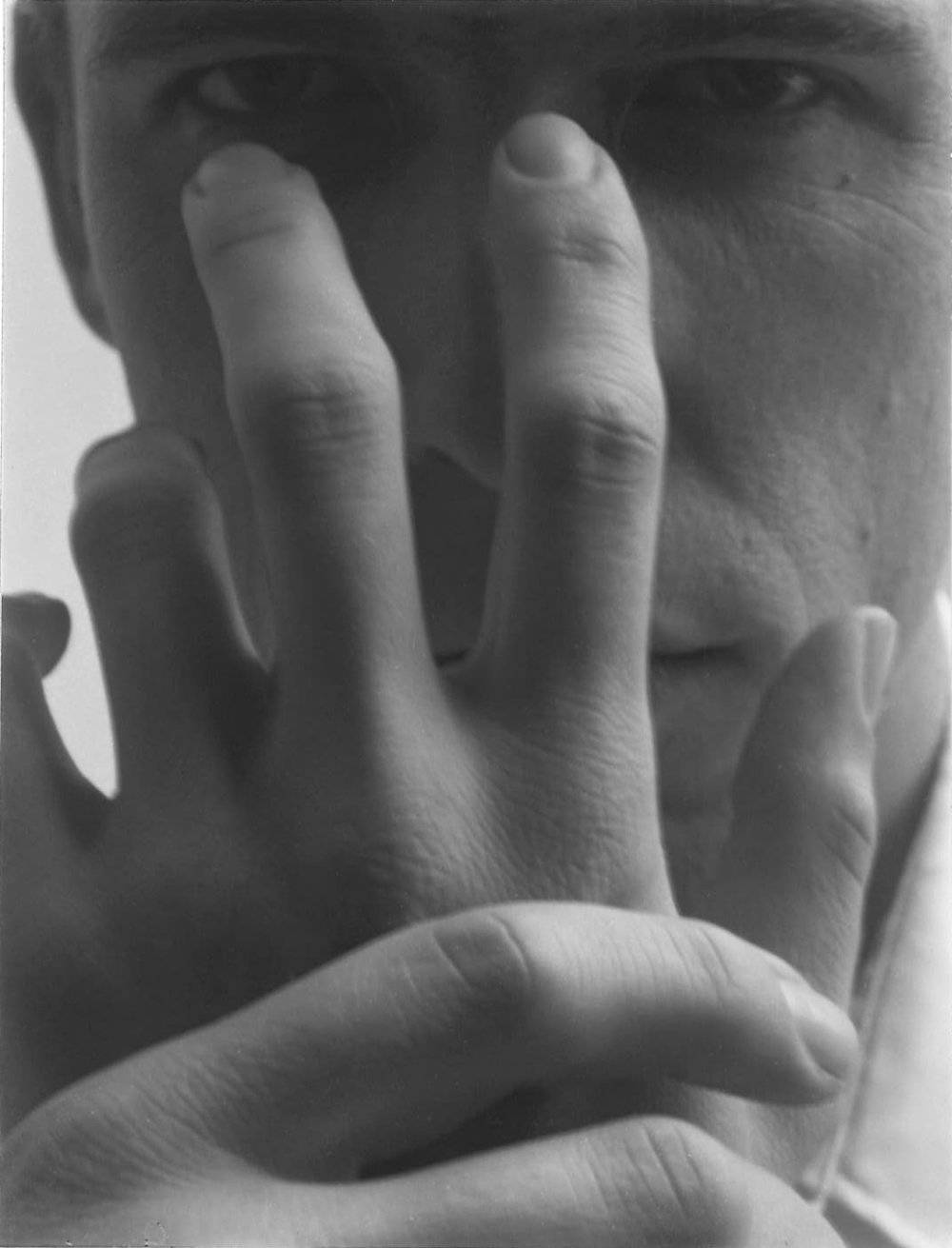

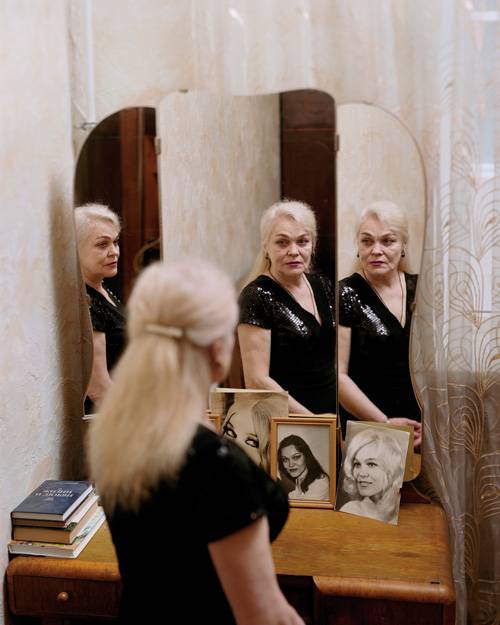

LR: The two of you went in very different artistic directions, and one of the great things about the two shows in one museum is being able to see the two creative sensibilities. Yours I don’t know as well as his, and that is why it is such a revelation to revisit work of yours that looks so fresh. I am thinking especially of Mrs. Kilpatric (1974) and Motels (1974). Mrs. Kilpatric has the feel of so many attempts by younger photographers to do something with the portrait, to dial back its intensity and simply register affection and surprise.

MM: It’s nice to hear you say that because that is more or less what I intended. Mrs. Kilpatric lived near me in Santa Cruz, and I would see her every day. She was sixtyish, and she seemed such a motherly figure, unlike my own mother, so one day I asked if I could take her picture. After that, we came to a sort of agreement: I would take her picture whenever I could or the mood struck me, and I would give her a print of each picture. There she was, watering the lawn, or holding a fishing rod. I never thought of it as a project.

LR: At some point everything became a project.

MM: Yeah, at some point you realize you have to plan things. But in the ‘70s it was the fashion to wear a camera around your neck and just shoot everything, as a part of daily life. It had something to do with the Vietnam War, I think, and feeling a need to define in some way what it meant to be American.

LR: Very much like today, I believe. I think that’s on the mind of so many young artists, even the ones who appear to be the most casual. It’s a kind of burden.

MM: Except that photography today has folded itself so completely into social media, into communicating where you are, right now. There are wonderful projects in this regard, and there are a thousand ways to think about photography now. But in the 1970s, there weren’t that many. It was a little world, and at some point, in spite of the prevailing opinions about what it should be, you just said, “fuck all that, let’s do what we want with the medium.”

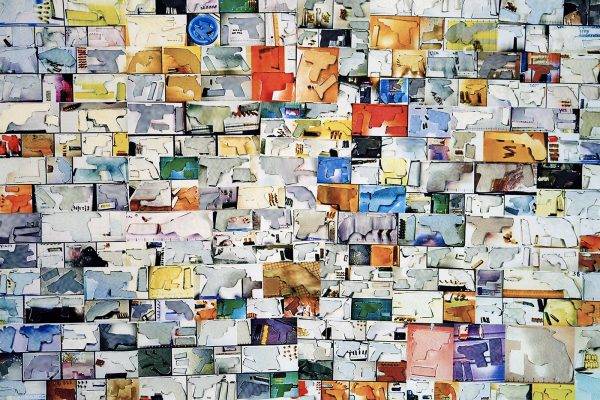

LR: One of the things you could do was to train your camera on things that really weren’t considered artistic subject matter, like vernacular architecture, specifically motels.

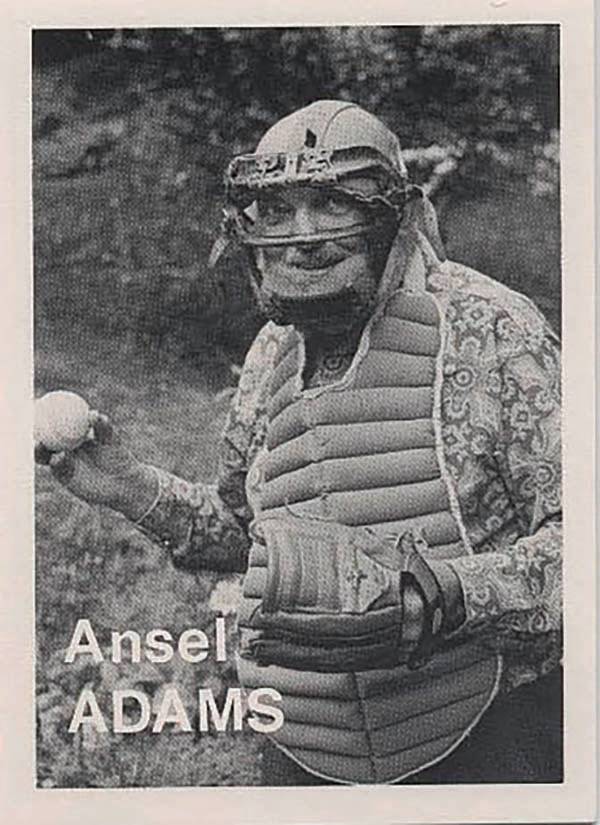

MM: Of course Ed Ruscha’s ideas were in the air, and before him Walker Evans had mastered that unexpressive, reality-show approach to American streets and buildings. But I liked motel postcards, those dumb, banal pictures of boring architecture, with a model standing next to the pool, in lurid color, printed out of register. My girlfriend at the time and I even figured out the distributors so we could buy those commercial cards in bulk, but I wanted to make something out of them. Anyway, when I was working on the baseball card project [The Baseball-Photographer Trading Cards], I was traveling across the country, staying in a lot of motels, and I thought, I’ll just make my own postcards.

LR: Today those pictures have a surprising poignancy.

MM: You can’t avoid a certain nostalgia, but that wasn’t my idea. The poignancy comes from the fact that such places cannot exist anymore. Chains have largely made them disappear. We can see in their architecture, in their colors and neon and swimming pools, what their appeal was – that the motel expressed a vision of a place, not just a place to stop on the way to somewhere else but a place to come to, a special place of fantasy. If you got off the interstate, that’s what you could find.