How does a country or a community discover itself, except through its artists, those peculiar people who are somehow able to enter the minds and hearts of others and provide indubitable testimony to their reality. Alec Soth has displayed a quality of sympathy through his photographs for more than two decades. His recent intuitions, at once modest and profound, are on view in a new book published by Mack, I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating, and in several exhibitions: at Weinstein Hammons Gallery, Minneapolis (March 15-May 4), Sean Kelly Gallery, New York (March 21-April 29), and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco (March 23-May 11). Soth has also curated an exhibition, A Room for Solace: An Exhibition of Domestic Interiors, for the AIPAD Photography Show, April 4-7.

Lyle Rexer: I feel I should start this interview by making a point about your interviews. As a writer interested in background, I appreciate the fact that you’ve done so many.

Alec Soth: I’ve come to see it as part of the job, really. Like writing grant proposals. It’s also a way of reaching a larger audience. On the other hand, I learn what my work is about by talking about it, the way you probably understand what you think by writing. For me, it is thinking out loud. This is especially true of my latest work. How do I talk about it? I find myself fumbling for a convenient description.

LR: Well, how do you talk about it? What is it?

AS: It’s certainly not high concept. It’s largely portraits, with some interiors. For this body of work, I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating, I wanted to get back to just making pictures, just being a photographer. I hope that comes through in the exhibitions and in the MACK book. I have tried to shape the project more by impulse than calculation.

LR: As if you weren’t always, first and foremost, a photographer?

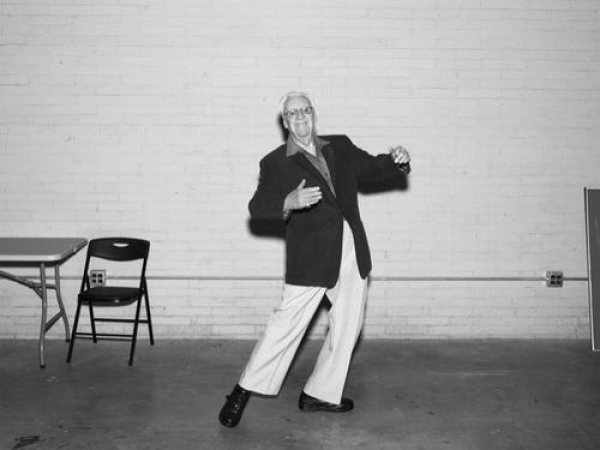

AS: My problem is I take myself too seriously. For example, I love ping-pong. It’s relaxing, I love to play, and I’m not out to be the best in the world. But at some point I got a coach, and I became more involved, and that began to ruin it for me. I already have that thing I stake my identity on. At the same time, I felt I needed to loosen my grip on photography; to be present to the photographs and not pursue some larger construct as I often had in the past.

LR: That’s interesting. Your previous series, Songbook, also seemed like a break – shooting in black and white with just a flash and a zoom, traveling randomly, gathering these pictures that seem goofy, sad, mysterious, all over the map.

AS: My friend Brad Zellar and I both worked for small newspapers, and we had this idea: what if we went back to doing what we first started out doing, small stories in places that interested us. Just traveling to do that and do it quickly. Shoot black and white to avoid the problem of the icky yellow shirt. Digital made sense. It was refreshing to get away from large-format film and the slow work it requires. Photography has always been linked to its technology, and the choice of camera in an important sense determines the work.

LR: I often see Garry Winogrand referred to as Walt Whitman with a camera. I don’t buy that at all, but Songbook clearly has Whitmanesque overtones.

AS: I love Whitman when I’m in a great mood. When I’m not, I’ve had to say “Enough already!” I’m so not like him. If you sat next to me on an airplane, I wouldn’t talk to you. I have a darker side. But with Songbook, Brad and I went in search of “community.” Does it exist? You know that whole idea of “bowling alone.” But we found that a sense of community does exist. People were open and welcoming. I came away with – I wouldn’t call it optimism, exactly, but a sense that yeah, America was still happening. Several years later, now, in Trump’s America, I’m asking myself, was I crazy?

LR: I think many of us are asking ourselves the same question in the post-Obama era. But you stopped shooting for some time after Songbook, and now you have returned to the large-format film camera and to making portraits, reminiscent of some of the work in Sleeping by the Mississippi but simpler, much less narrative – environmental, but only up to a point, to set a basic context.

AS: Even before Trump I was feeling a fatigue with my way of working. I stopped traveling, hung around, made sculpture. I also had a meditation experience that changed things for me. Not to go into detail, but I came out of it with the sense that I wanted to make something positive. At the same time, I was getting editorial invitations to shoot Trump’s America, and it just wasn’t appropriate to my mindset. I had this idea to get back to something basic, to become a beginner in the best way, to avoid notions of place (one criticism of my work has been that all the places I visit are the same place!) and get away from the idea of “America.”

LR: The portrait was the answer to that. There is something utterly mysterious about a picture of another person we don’t know, the simple fact of their appearance.

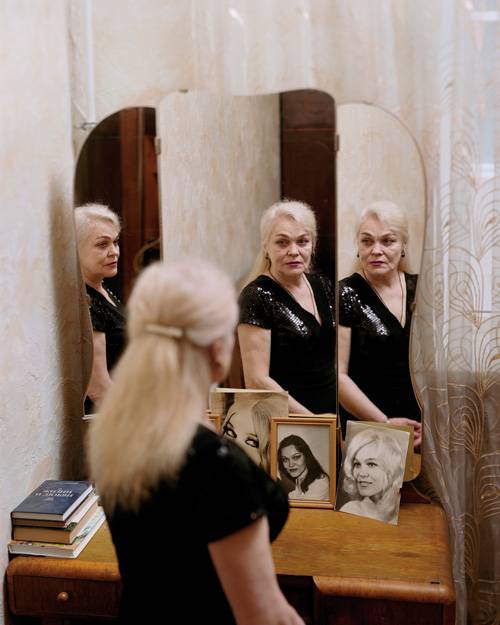

AS: I am intensely aware of the ethical issues of photographic portraiture, the problem of exploiting another person for your ideas. In my case, I always felt that what I was doing, apart from capturing a surface appearance, was showing the space between myself and the subject. Perhaps that skirts the ethical issue, but it also bummed me out. I came to think that all I was doing was photographing separation, or alienation. What I wanted to do is connect. Just me and another person in a room together, to be together, to talk, and for me, to look. So I decided that I would accept invitations to do things like give lectures, wherever I was invited, mostly in Europe. I would surrender to chance. Wherever I went I would ask the people sponsoring me to introduce me to people who might be good subjects to photograph, people who would be interested and willing. I would meet them in their homes, and I never tried to talk them into participating. I was tranquil about it. The camera felt like an easel again.

LR: This perennial problem of the portrait, of appearances that always suggest that what’s inside may be different from what the camera sees, or that there is a power struggle going on between the resistant subject and the penetrating gaze of the photographer – did you feel like you solved that with I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating…?

AS: People showed themselves to me, and I have come to understand that what I have been photographing is a dynamic, an energy that passes back and forth between us. My camera remains at the surface, and I can never penetrate to some inner core, but I know it’s there. It’s like the Wallace Stevens poem Gray Room, which has a line that I have used for my title. The poet contemplates an isolated person’s presence in a room as unknowable, and yet, as he says, “I know how furiously your heart is beating.” This is a person, the person is there, and you know it. This is what you connect to, and this is what you render.