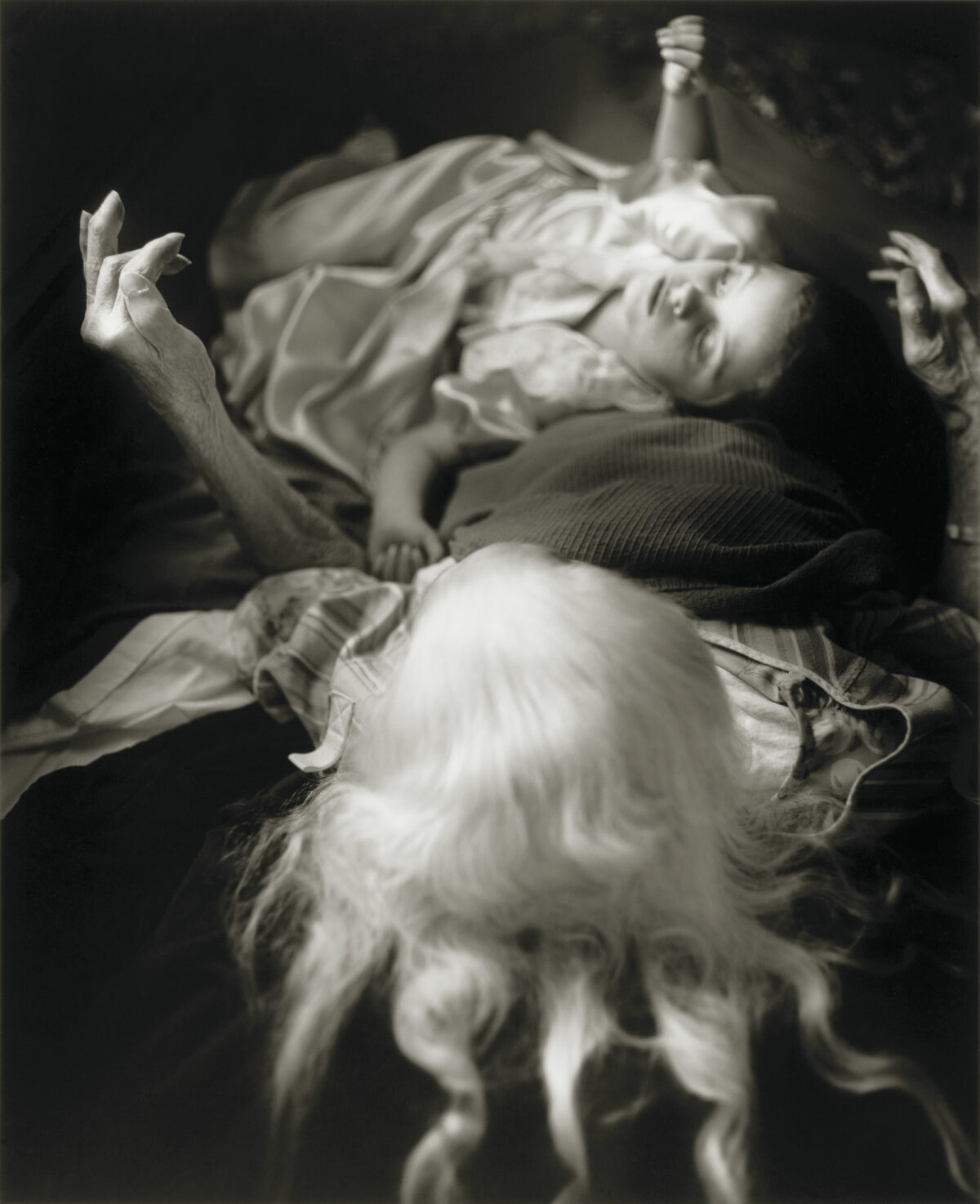

A conversation with photographer Emmet Gowin tends to peregrinate. It may touch on anything from an obscure natural history text to a poem by William Blake to an anecdote about the philosopher/photographer Frederick Sommer. The pleasure’s in the journey. Likewise, Gowin’s photographs illustrate a fascinating journey, from early black-and-white portraits of his wife, Edith, and the world of their home in Danville, Virginia, to more recent catalogues of mariposas nocturnas (moths) shot in the forests of Central America. These hypnotic grids have been published, with a long essay by Gowin, by Princeton University Press (Mariposas Nocturnas), and they form the core of his current exhibition at Pace/MacGill Gallery: Here on Earth Now – Notes from the Field (through January 6, 2018).

Lyle Rexer: I recently read an interview with you in which the interviewer seemed genuinely impressed that a photographer might have a broad range of reference, as if this were an odd or remarkable thing.

Emmet Gowin: I didn’t used to admit it, but by 12 years old I had read the Bible cover to cover several times. As a graduate student at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), I wrote on Kierkegaard, especially his discussion of the story of Abraham and Isaac, which he tells in a powerful way. Growing up I didn’t have lots of books, but I remember going to visit Frederick Sommer in 1970 and asking him to draw up a reading list for me. It was huge. At one point, we went to a bookstore together, and each of us came out with at least 25 books.

LR: I know that your father was a Methodist minister, and the reference to Bible reading strikes a note with me. I think of your photos – and of course, Sally Mann’s, since she has written quite a bit recently, and she is also from Virginia – as anchored not only in a place but also in a rhetoric. I would even say they are biblically inflected. Probably that’s the wrong word, or it sounds too nativist. Maybe reverential is what I’m looking for.

EG: I’m certainly not a fundamentalist. I am uncomfortable with fundamentalism in any form. Long ago I knew it was exclusive, not inclusive. Perhaps what you sense is the feeling of photography as a calling. In 1965, when I was entering RISD, I received a notice to report for military service. They were ready to muster me in. In fact, I had never bothered to register for the draft. My father was a pastor, and where I came from, the only reason you would answer such a government notice was to get a document to prove you were old enough to drink alcohol, and my parents would never allow that. At the draft board, all the people facing me were women, and they were all local. They understood my situation immediately. Likewise, when I insisted that I could not take someone’s life. I could be in the military in another capacity, but carrying a gun I could not do. So I was released from military service for graduate school, and I always had the sense that I was carrying out an alternative form of service, one that required of me respect, attention, and an appreciation of what I can only call heaven on earth. Like my father’s desire to become ordained, this was my calling.

LR: There are so many forms of heaven on earth. Art is one.

EG: Art and art history saved my life – or at least transformed it.

LR: Mine, too. My art humanities professor, Gene Santomasso of blessed memory, told us to go to the Met to see if they paid too much for the just-purchased portrait of Juan de Pareja by Velázquez. It was a set-up. He just wanted us to spend some time with the picture. That was all it took.

EG: As an undergraduate I took Introduction to Modern Art, and then other art-history courses. In them I connected to a long arc of tradition, with something in common to all periods. It was the sense that these objects embodied qualities in very specific ways. Parts were related to each other, and in these objects we experience rhythm, color, form, smell, texture, radiance, mystery. All these are in the object, every time we engage it. Art became, for me, a vehicle for re-experiencing reality becoming more manifest. What sort of art might spark this re-experience? You can never predict. Renaissance art? Chinese painting?

LR: Another form of heaven on earth is living things, mariposas nocturnas, moths. These are stunning “portraits,” but it surprised me when I saw you print them in grids.

EG: Decades ago, when the Bechers [Bernd and Hilla] published the book Anonymous Sculptures, I called Fred Sommer and asked him if he had seen the listing for it. He said, “I already ordered it.” The work suggested something that anyone could understand; it was a kind of teaching through form. It showed how things exist, in their adherence to pattern and deeper regularities. Not all subjects can or ought to be treated this way. I started out making these photos when the moths would come to my tent in Panama. At one point I met a young biologist from the Organization for Tropical Studies in Costa Rica, and I questioned him pretty intently about his work. Finally he asked, “Who are you, anyway?” I told him my name and that I was a photographer, and he said, “I’m pretty sure we studied your work in photo class.” So he asked me to come to the research station and said that I could follow him around and ask questions. Only years later did I find out he had actually vacated his room for us, Edith and me. In any case, I got more deeply into this, over time photographing species that had never been photographed alive and in some cases described and named before. At one point a friend at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama asked me to make a poster of the moths, and I decided on the grid. It was then that I understood that this format allows anyone to make a comparative analysis of what real things look like. In a sense, it puts control back in their hands, to study and consider. The urgency and the interest will come from them.

LR: In this time of environmental pillage, do you give the work a political reading?

EG: People think taking a political stance equals producing propaganda, and we forgive slack or sloppy pictures for their messages. But every picture has a political import, in what it leaves out and in the way it treats what it puts in. What we choose as opposed to what we don’t choose. I think of Bob Adams and his pursuit of grace, luminosity, gentleness, and exactitude. Choosing to make family photographs during a terrible war in Asia was another kind of political stance. I believe that if my pictures provoke an aesthetic response, they are doing their job.

LR: I’ll ask you the same dumb question others have asked: What’s your favorite moth?

EG: The whole book.

LR: Finally, apropos families (since you mentioned it), in the Pace/MacGill exhibition, there are also pictures of Edith, your muse. Some of these were done at home, some in Central America. How do you see their relation to the moths?

EG: We must bridge the false separation between human beings and nature. Human families, after all, are a subgroup of all natural families. A moth or a beetle is a being which we are not, but we exist as they do, as form and structure. We are works of nature, no less than they are, pieces of the natural world.