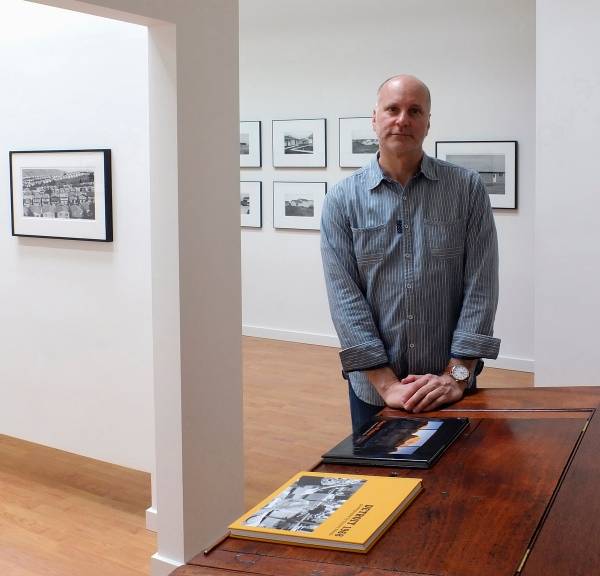

“These pictures,” Minor White wrote of his friend Rose Mandel’s oeuvre, “are an example of a person deliberately using photography as an art medium.” His emphasis was on “medium” as much as on “art:” Mandel, whose work is on view through January 13 at Deborah Bell Photographs, obsessively and elegantly drew focus to the materiality of her photographs, treating the gelatin print like a canvas on which various types of markings could be made.

A Bay Area resident, she shot the lakes and coastline of the region, allowing the movement or stillness of water to settle into abstract patterns through long exposure. Four such prints hang in a row at the gallery, almost like a demonstration of texture. Untitled (1964) depicts a passage of dense ripples, like white chalk marks scraped onto a graphite surface. The sense of motion is palpable, but it has been arrested into unchanging geometrical form, which gives the work its tension. Breaking Surf (1964) a photo of Clear Lake, is brighter, with the froth of a wave emerging as a series of individuated white slashes.

Another series about water, hung on the opposite wall, is modelled on Abstract Expressionist paintings. These more naturalistic images show long rectangles of sky or sea framed, at one edge (either top of bottom) by a sliver of seashore or the horizon. The effect, as in Untitled (1962), which features of band of thin horizon sandwiched between inky bodies of cloud and sea, is of achingly sweet solitude.

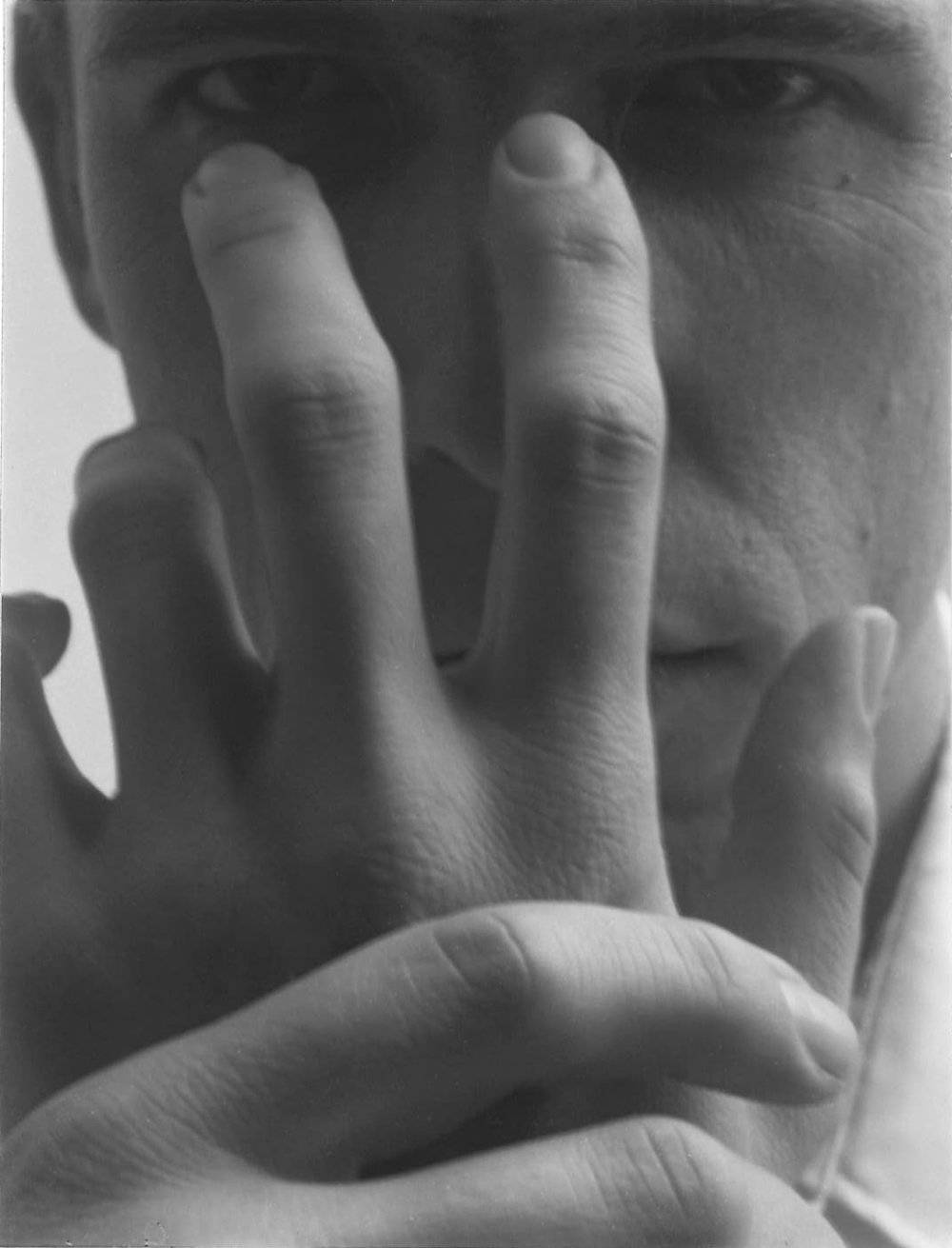

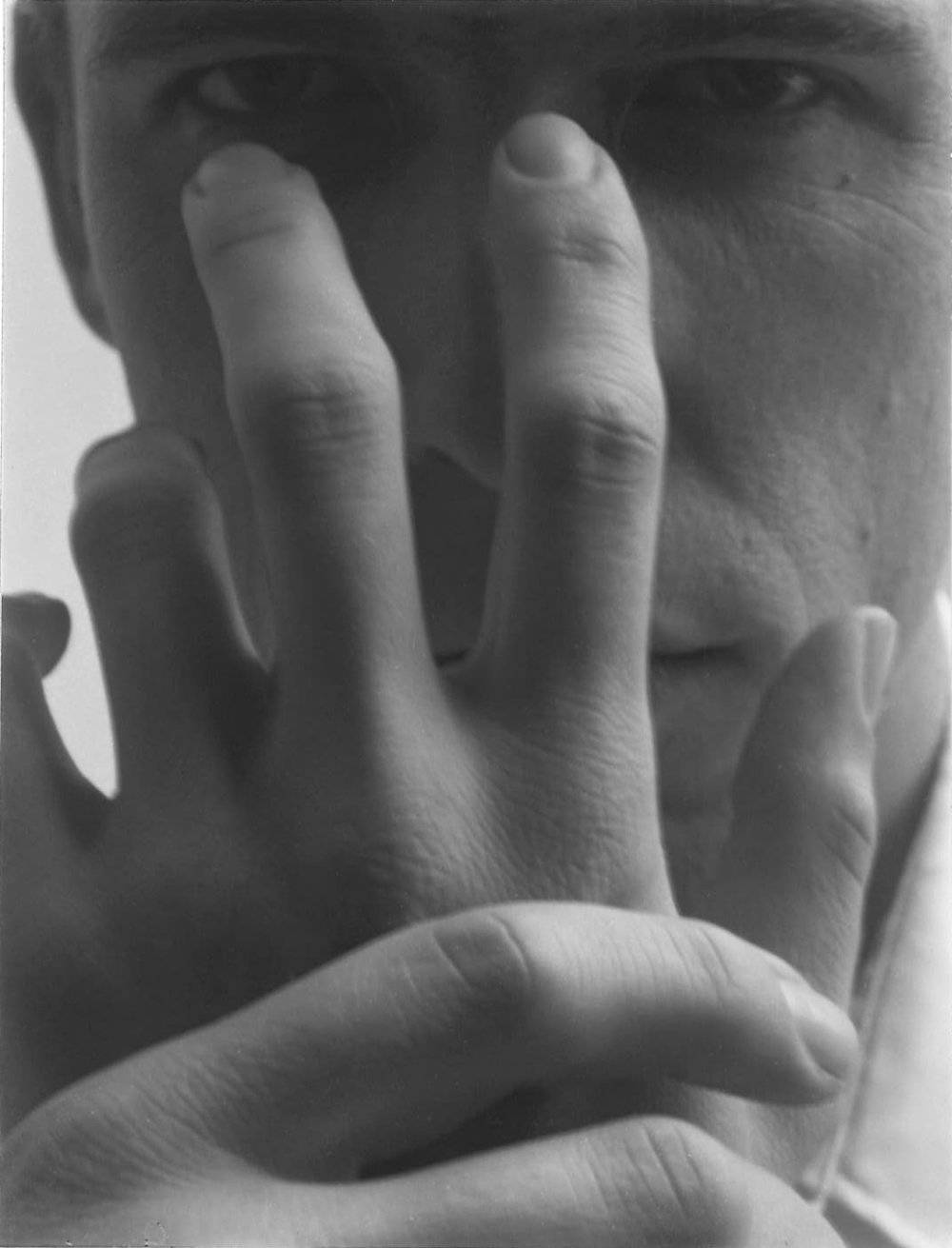

The show also features some of Mandel’s surrealist-inflected portraits that focus closely on a section of a sitter’s face or show them, as in Paul Wonner, through garden foliage. Finally, there are a collection of street shots, though these, too, are far in spirit from “straight” photography. Shooting into shop windows, or, in On Walls and Behind Glass, #1 (1948), from inside a shop, Mandel shows how the surface of a photograph can collapse various visual spheres – the shop items, the reflection on the glass, the cars and street outside – into a single two-dimensional surface. Life and its reflection, reality and daydream, here have the same texture.