Though artist Hank Willis Thomas is often referred to as a “photo conceptualist,” the medium he’s working in for his biggest collaborative projects this year is American democracy itself. In the run-up to the 2016 presidential election, Thomas and photographer Eric Gottesman co-founded the first artist-run political action committee. It’s called For Freedoms, and technically, it’s a “super” PAC, which means the group doesn’t contribute directly to any campaign. Instead, the goal is to raise awareness of the impact of money on our political system, while creating a space for discourse around the diverse and nuanced issues in politically engaged art.

The PAC takes its name from a series of iconic political artworks that did not present a particularly diverse, nor nuanced view of American values: the famous “Four Freedoms” paintings by Norman Rockwell, based on Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s influential 1941 State of the Union address. The celebratory view of America depicted in Rockwell’s paintings Freedom of Speech, Freedom from Want, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Fear, was used by the U.S. Treasury to sell war bonds. The work of the For Freedoms artists, most of it very recent, updates this notion of a celebration of, and a yearning for, freedom, and concerns itself with a broad array of issues, from gun violence to racial and gender inequality, environmental crises, and prison reform. Reflecting the founders’ backgrounds, nearly half of the work is photographic, including works by, among many others, Wendy Ewald, Jim Goldberg, Mikhael Subotzky, Alec Soth, Andres Serrano, Xaviera Simmons, and Thomas’ mother, the curator, artist, and scholar Deborah Willis.

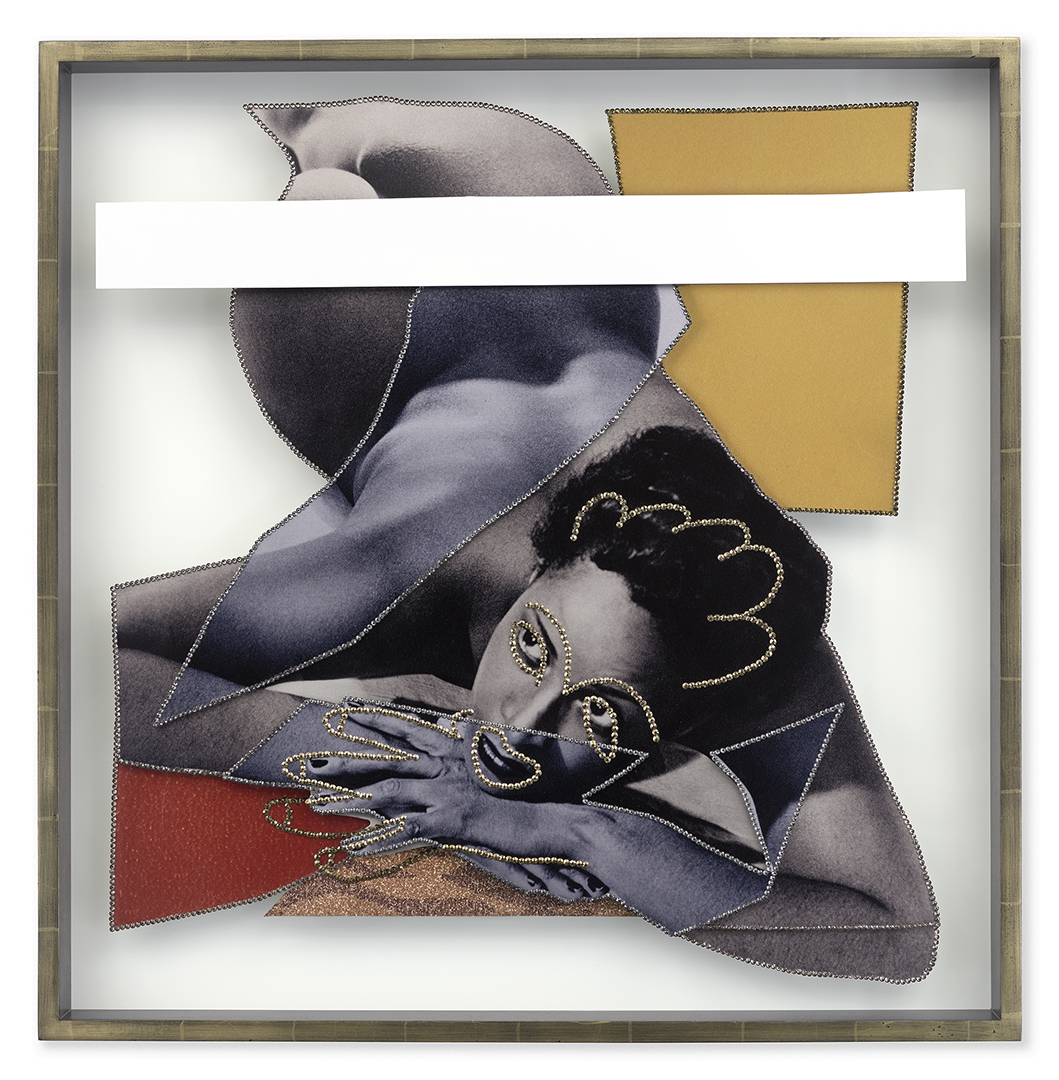

Selected works will be transformed into advertisements – just like the Rockwells were – and placed on billboards, in subways, and in digital space. But unlike the Rockwells, many of the works by the more than 50 artist-collaborators who are taking part in the PAC get at their respective concerns in elliptical ways. In Carrie Mae Weems’s work American Monuments II,

the artist stands in a somber black dress before the Lincoln Memorial, confronting the relationship she holds to power and history as an African-American woman. Also included is an oversized portrait of a glowering Donald Trump, by Andres Serrano. The image is from Serrano’s “America” series of 2003, portraits of both celebrities and other Americans dramatically lit against a studio backdrop, which reads like a more sinister version of a department store family portrait session. Trump, in the context of these other Americans – a boy scout, an escort – is part of a garish, bizarre parade, but the portrait taken alone is more enigmatic. In Jackie Nickerson’s photograph Flag, a shirtless, tattooed African-American man holds a burning Confederate flag aloft.

“Freedom of speech is obviously central,” says the photographer Wyatt Gallery, who serves as the PAC’s executive director. “We’re giving artists free reign to talk about whatever issues they want to discuss with their work.”

An exhibition of all of the works was held at both Chelsea locations of the Jack Shainman Gallery this summer, and the gallery also served as the super PAC’s headquarters as well as the site of various talks and other kinds of public programs. “It’s a curatorial project, and a PR project; there are several events, and actions, and now we’re focused on designing the ads,” said Thomas, as a whirl of volunteers, visitors, and artists buzzed about the gallery. “In the group we’re constantly debating, ‘What is political speech?’” That discourse itself is part of the point of the super PAC, and it’s central to both the collaborative creation of the project, and the audience’s engagement with it.

Free speech, and dialogue that is both personal and political underscores the other collaborative projects in which Thomas participates, as well. In Search of the Truth is a project of Ryan Alexiev, Jim Ricks, and Thomas, who are all in ©ause Collective, a group of artists, producers, and scholars who’ve collaborated on politically engaged public art installations over the last ten years. In Search of the Truth is a project that comprises a large inflatable bubble-shaped, room-sized video recording studio (“The Truth Booth”). Inside, members of the public record a two-minute video in which they finish the sentence: “The truth is…” This simple conceit has elicited powerful recordings from around the world, including Ireland, Afghanistan, and South Africa.

This June, the Truth Booth set out on an epic domestic tour to gather as many diverse recordings as possible ahead of the fall election. “Art is often dismissed on the grounds that it speaks to a certain level or class, you have to have a special education or talent to participate in it,” says Thomas. “The creative process is much more intuitive and closer to our everyday lives. We’re trying to democratize what we call art. It’s about being inclusive. Everyone owns the Truth. No one can claim it.” These testimonies range from the very personal, to the political, to the existential. A boy of about 12 with autism declared, “The truth is, I don’t think we need your cure for autism.” An African-American teen confesses: “The truth is, I’m scared. Everyday. Walking down the street.”

Working with partner organizations nationwide, ©ause Collective member Will Sylvester travelled with the Truth Booth to dozens of cities before hitting Cleveland during the Republican National Convention, then Philadelphia during the Democratic National Convention. The tour continues through the fall, and compilations will be made into art videos, re-edited for various themes and venues.

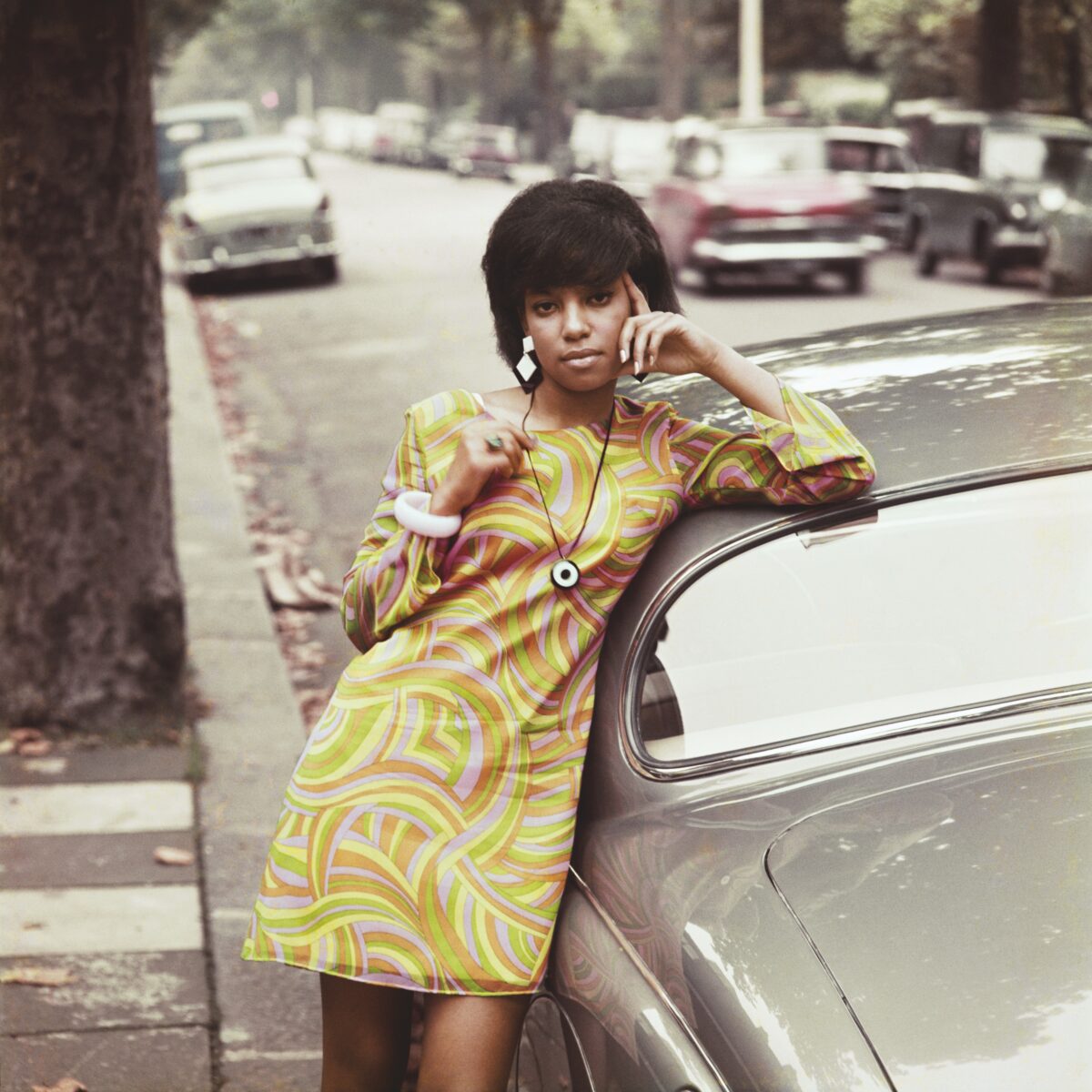

Meanwhile, Question Bridge, 2012, an important touring transmedia project on which Thomas collaborated with artists Chris Johnson, Bayeté Ross Smith, and Kamal Sinclair has had a long life. Following several national venues in 2016, the work will be on view at the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Florida, from October 18 to December 18. In Question

Bridge, black men address a video camera from various sites across the U.S.; disparate in age, class, values, and interests, the men ask a question about their lived experience in regard to race: “How do you know when you become a man?” “How does the representation of black folks in media affect who you are?” The faces of several men are sometimes arrayed on the screen, listening to others. The powerful effect of the piece is to allow for a conversation among a group of black men who are as diverse as humanity is, upending the prevalent monolithic concept of African American Man, while providing a form of community in which the multifarious burdens of American racism can be unearthed and examined.

The piece can be experienced on the web, as an app, and was also published in book form (Aperture, 2015). But like the other projects in which Thomas is involved, Question Bridge reaches its fullest potential in a live setting, where the dialogue begun in the work can engage with public space.

In yet another year in which police violence against black people arises all too often in our news cycle, we have frequently heard the entreaty “We need to have a conversation about race.” Question Bridge is one version of what that conversation can be, and a much needed one.

In fact, each of these projects: For Freedoms, In Search of the Truth, and Question Bridge are instructive, in terms of how real dialogue about divisive topics can transpire through art.

Real conversations and real collaboration: the truth is, this is what democracy looks like.