In the history of 20th-century photography in the West, one of the major paradigm shifts occurred just after the middle of the century, give or take a few years. From the early 20th century onward, what might be called the “photograph as document” aspired to universal, transcendent messages (think of the humanist documentary of Lewis Hine, Dorothea Lange, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Roy DeCarava, and scores of others). Beginning in the postwar period, with the careers of Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, and Garry Winogrand, among others, the photograph becomes an expression of the unique vision of the photographer, or “photography as sensibility.” By extension, this shift also entails the photograph as an exploration of photography itself. This shift is, in many ways, the primary object of exploration in the work of Lee Friedlander.

In Lee Friedlander Framed by Joel Coen at Luhring Augustine through July 28 (with an overlapping exhibition at Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco that closed at the end of June), the director of Fargo, The Big Lebowski, and No Country for Old Men, among other critically acclaimed films, presents an incredibly cogent version of Friedlander’s singular approach to picture making. His choices do not follow any chronological order, or adhere to any specific theme or subject matter, though of course, one can’t help attempting to discern the sensibility of the filmmaker in this compact survey of 51 works.

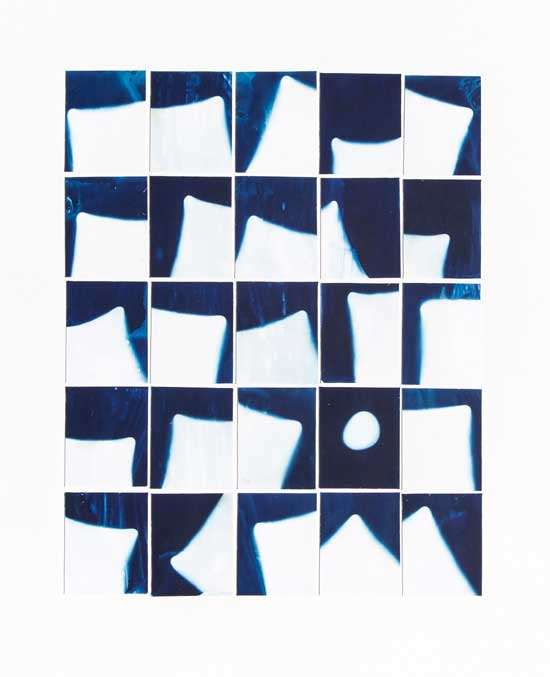

While the photographs on view span 60-plus prolific years, Coen’s selection has a clear logic. The works, which Coen chose along with his wife, the actress Frances McDormand, are united by what he describes in the afterword to the show’s catalogue as, “Lee’s unusual approach to framing – his splitting, splintering, repeating, fracturing, and reassembling elements into new and impossible compositions.” As a filmmaker, Coen wrestles with how to create atmosphere, narrative, and cinematic logic out of a sequence of images. In a much more oblique and allusive way, Friedlander has set himself a similar set of problems within the constraints of a single frame.

In an Artforum review of Friedlander’s 1975 show at the Museum of Modern Art, artist and critic Martha Rosler wrote that his work is characterized by “the voraciousness of a view that yields, in good focus and wide tonal range, every detail in what passes for a perfectly ordinary scene, the often kitschy subject handled in a low-key way, the complete absence of glamor, and the little jokes, these put intelligence and humor where sentiment or anger might have been.” Coen’s selection reveals an intuitive understanding of Friedlander’s approach. The slideshow accompanying the exhibition highlights the ways in which Coen has discerned pattern, repetition, and visual rhymes in Friedlander’s photographs. By enlarging them on a screen and allowing only a few seconds for our eyes to take in each one, Coen has demonstrated the way Friedlander’s careful control of form and compositional elements heightens the viewer’s awareness of just how space and depth and our perception of them are manipulated in a two-dimensional field.

In the first sequence in the show, vertical elements intentionally disrupt the path of our vision. In so many Friedlander photographs, something is always getting in the way of what we might imagine to be the main subject of the picture: a bridge cable, a raised foot, a flagpole, a statue, a street sign, an alarm box. It’s a signature Friedlander move that Coen has zeroed in on: creating a tension between the formal structure of the elements within the composition and the way our minds organize that optical information into an ordered scene. Another series of “frame-within-a-frame” pictures uses windows, doorways, or other objects to divide the space of the photograph in a way that again foregrounds the push and pull of its two-dimensional surface and the illusory depth of photographic space.

Friedlander pushes back, not with force, but with great subtlety, against the literal in photography. And like many scenes in the films made by Joel Coen and his brother Ethan, it is up to the viewer to decide whether they transcend the commonplace perception of reality, or if, somehow, they have entered into the realm of the surreal.