Stephen Shore is misunderstood. That’s a strange claim to make about someone with an enormous career retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art (opening November 19), enough books and exhibitions to fill a warehouse of CVs, and a clear vantage point atop an entire medium’s pantheon. But I think it’s true, and worth discussing. We live in the Age of Like. There was a Summer of Love, a Me Generation and now we have the Age of Like. You express your opinion by assenting that you like something, bestowing your brief blessings like a priest sprinkling holy water. If I were in charge of Instagram, say, I’d replace the Like option with Why I Like, so every pale naked assent would get dressed in explanation. And if you look at Shore’s Instagram, I’m certain most of those explanations would miss the point.

Stephen Shore is, above all, homo visualis. He is a seer, interested in the quantum calculations that accompany the seemingly automatic act of using a camera to translate the three-dimensional world into a flat photograph. I think of this process as the exact opposite of abstraction. A Stephen Shore photograph feels like looking at the world, the translation as precise as possible, a concerted effort NOT to abstract but to simulate or represent the experience of seeing. And unlike almost every other photographer on earth, I would contend that he is only marginally interested in what he sees. His pictures are largely not of anything. They are experiences, not subjects. When I first met him in the mid ‘80s, he was making spare, distanced landscapes of Montana, Texas, and Scotland. They almost completely lack content. We look now at his most well-known images, from Uncommon Places and American Surfaces, and we see “the ‘70s.” But it wasn’t “the ‘70s” when he made those pictures, it was NOW. Aperture’s new, enormous book of this work is being published as far forward from its making as Shore was then from Walker Evans’s American Photographs, and Shore was savvy enough to see Evans’s work stripped bare of nostalgia, not as “the Depression,” but as Evans’s NOW. We need to see Shore’s work with the same sober clarity.

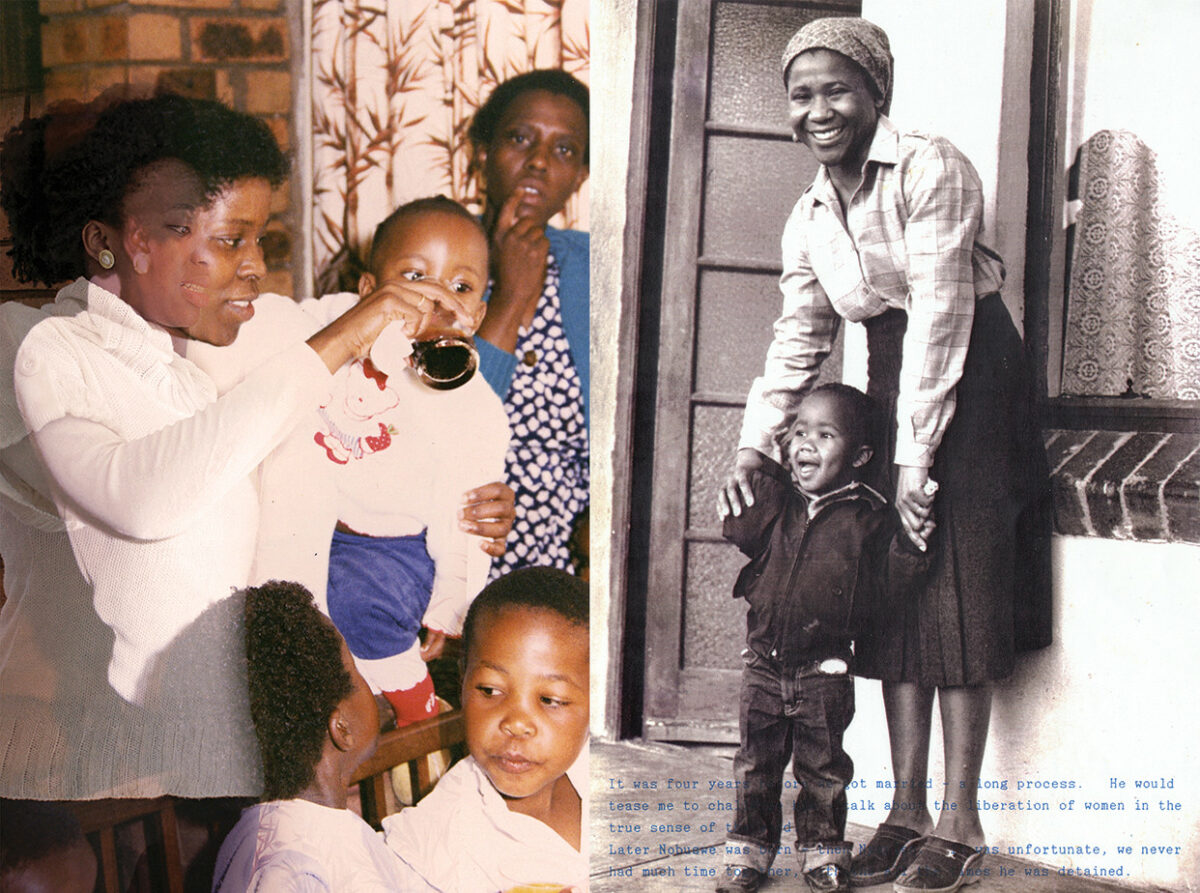

This is evident from Instagram. Here’s his post (below) from the day before this writing, September 16, 2017, with 1,098 people having liked it. Do you like this picture? Why do you like it? The comments betray nothing. The picture betrays little more. It is as not-about-anything as a picture can be, as far from, say, Richard Avedon’s slump-shouldered Marilyn Monroe looking vulnerable and introspective as Seabiscuit is from a paramecium. But Avedon and Shore’s pictures share essential photographic DNA. They are square and grey and visually compelling, crackling with light. They are hard to look away from. In conversation about photographs he likes, Shore will commonly say that an image “pops.” This popping is the visual equivalent of a sonic boom, the quality a picture has when it breaks the barrier between the ground and the ground glass, between something you overlook and something seen. Shore is interested in this Pop, and he is willing to ask you to look hard at it, especially when a square of dirt in Upstate New York – instead of Marilyn Monroe – is doing the popping. There is a challenge in any Stephen Shore photograph, a steely-eyed dare, to look at this, this, this, despite there not being anything obvious or conventional to look at. His work is difficult, and his career, despite his success and wide-ranging influence, is composed of pivots away from familiar expectations.

When Stephen Shore transferred from Columbia Grammar Prep School to Andy Warhol’s Factory at age 14, he found more than just Pop Art 101; he enrolled in an artistic stance. Arthur Danto wrote generously about that stance: “Warhol’s thought that anything could be art was a model, in a way, for the hope that human beings could be anything they chose, once the divisions that defined the culture were overthrown.” Declaring commercial illustration fine art and naming street hustlers Superstars were acts of radical democratization, but, in a tradition that goes back at least to Caravaggio painting Christ with dirty feet, were also acts of cultural rebellion. Leveling a playing field is done with a bulldozer. At the Factory, Shore was content to document his extraordinary surroundings in the style of any talented high school photojournalist, but beyond its confines, as this retrospective shows, Shore became the essential photographic Pop Artist, always placing the everyday on a set of pedestals while elusively, coyly pirouetting from project to project, refusing to be pinned down, out-hustling our easy understanding. From his early exhibition of serial, conceptual images at the Metropolitan Museum of Art at age 24, to his current work on Instagram, Shore is easiest to understand as an artist who doesn’t want to make it easy for you to understand.

I’m always disappointed when publishers and institutions use his U.S. 97, South of Klamath Falls, Oregon, 1973 or Sunset Drive In, West 9th Avenue, Amarillo, Texas, 1974 as cover or promotional images. These visual puns stand out like rodeo clowns at a robotics conference and are too easy, too illustrative, to take meaningful measure of his work. Stephen Shore isn’t joking around. Like sex, art only feels like anything if it creates friction, and the particularly pointed way Shore removes seemingly unremarkable sections of visual flux feels most pleasurable when it burns a little. Imagine receiving these instructions from the career gods: “OK. I see here you are going to be a photographer. That’s great! Now, you won’t care at all about the content of the pictures…and even traditional ideas of form – composition, balance, et al. – won’t apply to you. Instead you’ll skim emphatic remarks from the slow muddy stream of the unremarkable.” Hundreds of thousands of Instagrammers are doing exactly the opposite: assuming that we are interested in their sandwich. In 1972, Shore knew we weren’t interested, and that we would resist being dragged by the scruff of our necks over to the diner Formica to stare at a goddamn sandwich on that heartless oval plate – in color no less – the camera an odd distance from its subject, too far for a product shot, the frame casual and unplumb (but somehow on kilter), the flash a symphony of overkill, but that through all that friction, the picture would burn like a meteorite hurtling through the atmosphere of our inattention.

Shore is asking an endless chain of questions about how a photograph can be so blank, so obvious, so divorced from traditional artistic conventions, and still be compelling. And he doesn’t wait around for us to find out. When Apple introduced its print-on-demand photobook technology in 2003, Shore leapt into this new medium the way Bruce Nauman and William Wegman did with the Sony Portapak, producing notational but essential works in the medium, each shot and edited within one day. All his finished books were collected by the Met and published in an enormous Book of Books, a massive testament to an artist dedicated to the immediate and the quotidian. In recent years, Shore has even turned his honed, non-partisan attention to more traditional documentary subjects. When I heard he was traveling to Ukraine to photograph Holocaust survivors, I felt the way I did when Bob Dylan was making Gospel records: this is another way to elude our expectations. Shore’s Survivors in Ukraine, as well as his work in Israel, show us how endlessly elusive this artist can be. Neither the legacy of the Holocaust, nor any cubit of earth in the state of Israel can be seen apolitically. But Stephen Shore approached these traditionally “concerned” photographic subjects astride and alongside (if not above) political dogma. Discussing a set of his on-demand iPhoto books, where he went out photographing when there were enormous world-shaking events, Shore has said, “On the days in which the Times ran a six-column banner headline, I would do a book on that day, that was not necessarily about the event, but it was what life was like on that day.” Homo visualis sees politics as another arena to be utterly, keenly seen, almost without judgment, a tactic which leads to implicit empathy. In Pompeii, you don’t see policy, you see the sides of buildings and cobblestone streets frozen in volcanic ash. You see what it was like to live there, and so you care.