As the divisions between mediums increasingly blur, and museums move towards less hierarchical department models, artists’ allegiance to one way of making art is becoming similarly elastic. Three notable shows in Northern California this summer provide examples of how sculpture, and the idea of sculpture, are explored in photo-based work: Erin Shirreff, Sara VanDerBeek, and Catherine Wagner each make photo-based art and objects that are deeply informed by sculptural concerns. All three artists create images and objects that explore art history, art, and its circulation and reception.

Considering printed images of objects, particularly big steel objects, is a key starting point for Shirreff. In 2005 she earned an MFA in sculpture from Yale, a department that allowed her to explore the conceptual and physical dimensions of her subjects, and from her first solo exhibition in 2009, she has considered and included photography in her practice. Her show, which will be on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) from July 20 through October 27 as part of the museum’s New Work series, includes photographic work as well as sculpture.

Shirreff is attuned to the fact that one image cannot possibly capture the full essence and dimensionality of, say, a sculpture by Tony Smith, an artist whose work Shirreff has engaged with over her career. In a segment on the television program Art21, she noted that after discovering images of his sculptures in monographs, she felt a disappointment in seeing the actual sculptures: “There was more romance and mystery in the image.”

In 2011 she began to delve more deeply into the relationship between the image and the three-dimensional artwork with an ongoing series called figs, as in the illustrations of figures in an art book. These are black-and-white photographs of sculptures she has made out of provisional materials like cardboard and foam core. Her figs attest to the intimate experience of viewing sculpture in catalogues, where one feels the texture of the paper, smells the scent of ink. Shirreff’s figs emulate printing signatures, where the configuration on press, before the catalogue is assembled with the correct pagination, might juxtapose two different sculptures of her own making, with the crease between them where the gutter will be in the book. Together they create a new form that functions visually, though it might be structurally unsound if it were an actual three-dimensional sculpture. Five new figs are included in the SFMOMA show.

Shirreff will also present three new dye-sublimation prints of photographs on metal that she has cut and re-assembled within the space of a frame. And two new bronzes in the show find the artist referencing her own work in a complex cycle of mediation: Looking at JPEGs of small, provisional sculptures she made in the past only in order to photograph them, Shirreff remade the works at a larger scale out of foam core and hot glue, then cast them in metal, taking care to maintain the imperfect joinery that resulted from her attempts to re-create these objects from online images. These works – which reference modernist sculpture in a general sense – raise fascinating questions about the distinctions between pictorial and dimensional representation.

These are not altogether new questions, of course. The SFMOMA show was organized by curator Erin O’Toole, who notes a precedent for this kind of hybrid exploration in the 1970 exhibition Photography into Sculpture at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Its press release described the exhibition as “the first comprehensive survey of photographically formed images used in a sculptural or fully dimensional manner.” The curator, Peter C. Bunnell, made the point that the work “embraces concerns beyond those of the traditional print, or what may be termed ‘flat’ work, and in so doing seeks to engender a heightened realization that art in photography has to do with interpretation and craftsmanship rather than mere record making.”

O’Toole is SFMOMA’s associate curator of photography, and while she put together the Shirreff show, she points out that rather than existing under the umbrella of her department, the show is under the broader purview of the museum’s recently formed contemporary art department, which oversees the New Work exhibitions. “I didn’t want to pull out the photo work and disconnect it,” says O’Toole. “The story is more nuanced when you see her photographs and sculptures in dialogue with each other.”

Sara VanDerBeek, whose recent work is on view at Altman Siegel in San Francisco through August 31, also engages in a dialogue with photography and sculpture. She cuts, grafts, tints, and superimposes elements within her photographs to address the complexity of dimensionality. Like Shirreff’s work, VanDerBeek’s photographic work has often included images of sculptures of her own making. Early on, in works shown at Altman Siegel in 2010, she built totemic sculptures that brought to mind tall, vertical works by Brancusi (noted as well for the photographs he took of his 3D pieces), but also architectural decoration. Some were photographed, others displayed in the gallery.

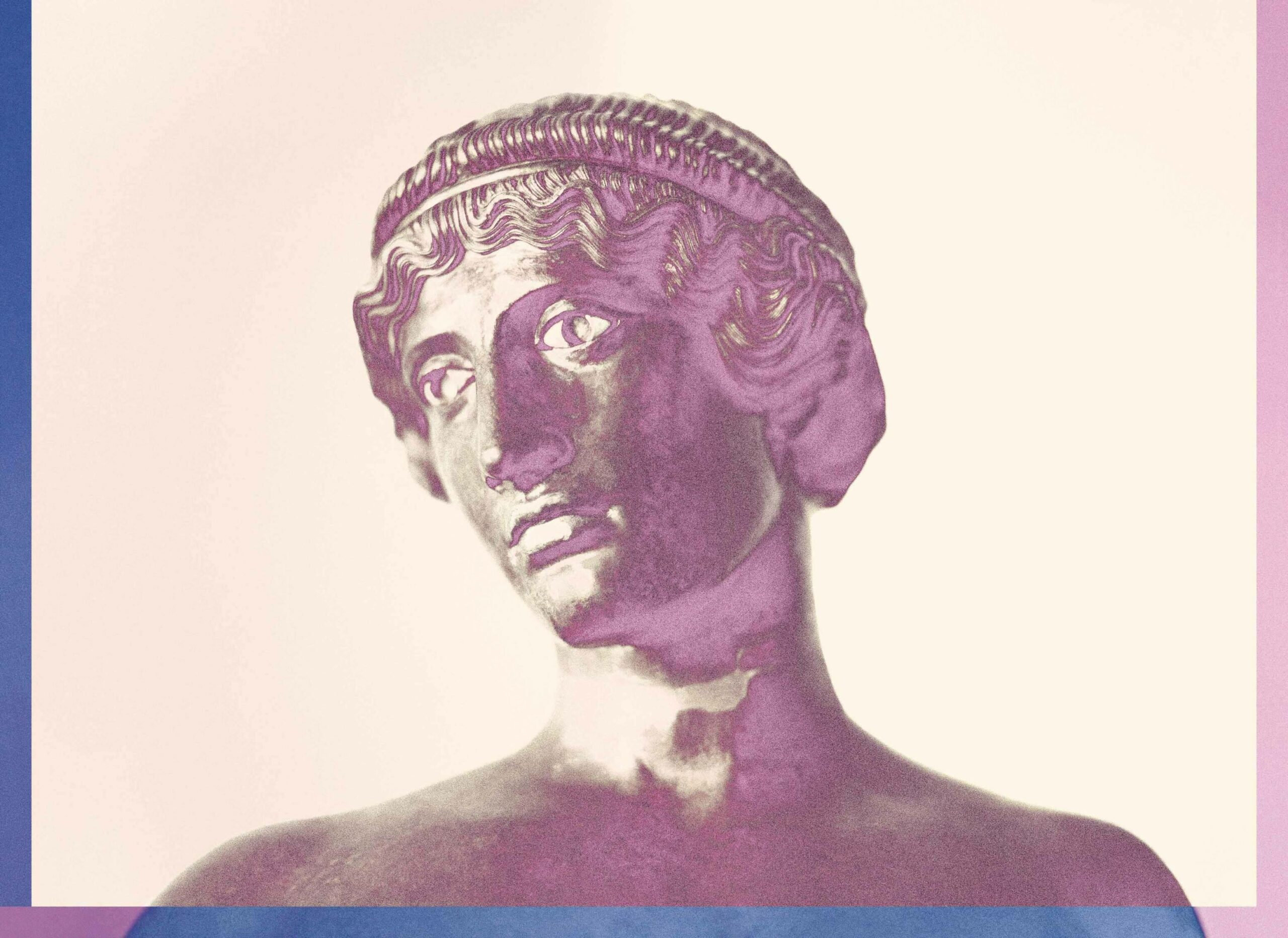

More recently VanDerBeek has turned her eye to museological objects, particularly ones related to women – Greek and Roman statuary, vessels, and textiles that she mines from museum archives. This exploration, fostered by a 2012 residency at Fondazione Memmo in Rome, is evident in her Women & Museums exhibition, on view through July 28 at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, which includes her own work along with resonant objects and photographs she selected from the museum’s archives, with an eye to representations of women and their cultural power.

In an artist statement for the exhibition, VanDerBeek wrote eloquently of her process: “I approach most objects with an earnest reverence and am often entranced by the object as I am photographing it.” After shooting many frames of film to get every possible angle of the object, she adds, she composes the final image, “with an aim to connect divergent forms and views in which to present a multiplicity of cultural and temporal perspectives.”

VanDerBeek then engages in acts of “mediation, cutting and cropping” that result in images in which the subjects’ colors are adjusted to take on preternatural tints and prints that can take geometric shapes beyond the square – works arrived at through Photoshop layering and a lot of color manipulation (she gives credit to her printer, Julie Pochron, with whom she works closely). For example, the dye-sublimation print, Women & Museums, 2019, features multiple images, including, in the lower left, one of a pale marble figurative sculpture that takes on a subtle lavender tone. This cropped image contrasts with two separate repeating images of a circular ceramic vessel tweaked to an otherworldly ultramarine. She describes her approach to color as “complex and somewhat alchemical in nature.” For works like the aforementioned, VanDerBeek was inspired by the original polychromatic state of now-pristine white Greek sculptures. The idea that so many ancient forms were polychromed, but faded over the centuries alludes to the way that photographs promise to preserve the memory of objects past. The unique, fugitive color tones of Polaroids, which many museum archives use to document objects in storage, have also inspired her approach to color, which she says is “about emotional state.”

The title of Catherine Wagner’s recently published monograph, Place, History and the Archive (Damiani, 2018), finds similar inspiration in museum storage – her photographs include artworks in crates and still lifes of display hardware. Like VanDerBeek, Wagner has also been inspired by historical sculpture in Italy – she was a fellow at the American Academy in Rome in 2013-14 – and by sculptural objects related to women. Her Rome Works series from 2014 focuses on gender dynamics in statuary, their museum display, and the armatures used to store and transport them. Her pigment print Artemis/Diana, for example, depicts the goddess of the hunt, known for her connection to the wild. Yet she is seen, in Wagner’s image, mid-conservation, flanked and restrained by vibrant blue scaffolding and straps. Such images of sculpture are described by the artist as supporting “the possibility of reading new narratives created through re-representation.” In other words, the figure of Diana, having been represented by a master sculptor for religious purposes, was then housed for centuries in a museum, and subsequently depicted in Wagner’s picture, suggesting that the foundations of historical narratives may not be as solid as we presumed.

The centerpiece of Paradox Observed, a show of works by Wagner at the San Jose Museum of Art through August 18, is an illuminated photo sculpture titled Pomegranate Wall, 2001. It combines aspects of photography, sculpture, and light, and must be negotiated physically, as both image and object. The monumental panoramic piece features sequenced images of the fruit imaged with an MRI – a form of cameraless digital photography. Displayed in a darkened room, this fusion of photography and sculpture bathes the viewer in a moody light. “The subject shouldn’t just have to function as a two-dimensional photo,” says Wagner.

Peter Bunnell’s observation in Photography into Sculpture is as true of Wagner, VanDerBeek, and Shirreff as it was of the artists in his 1970 show: “[T]hese photographers/sculptors are seeing a new intricacy of meaning analogous to the complexity of our senses … [moving toward] a visual duality in which materials are also incorporated as content and at the same time are used as a way of conceiving actual space.”