In a special feature, photograph magazine asked eight professionals in the field of photography to each select a single photograph related to the climate crisis that resonated with them in the last year. Their selections – from Dorothea Lange to Stephen Gill to Allan Sekula – suggest a variety of ways to contemplate the threats to our planet.

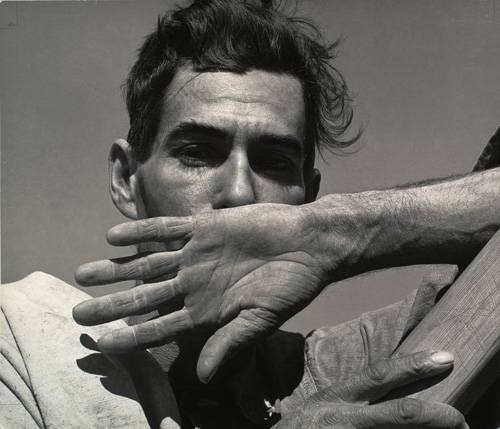

Courtesy The Museum of Modern Art

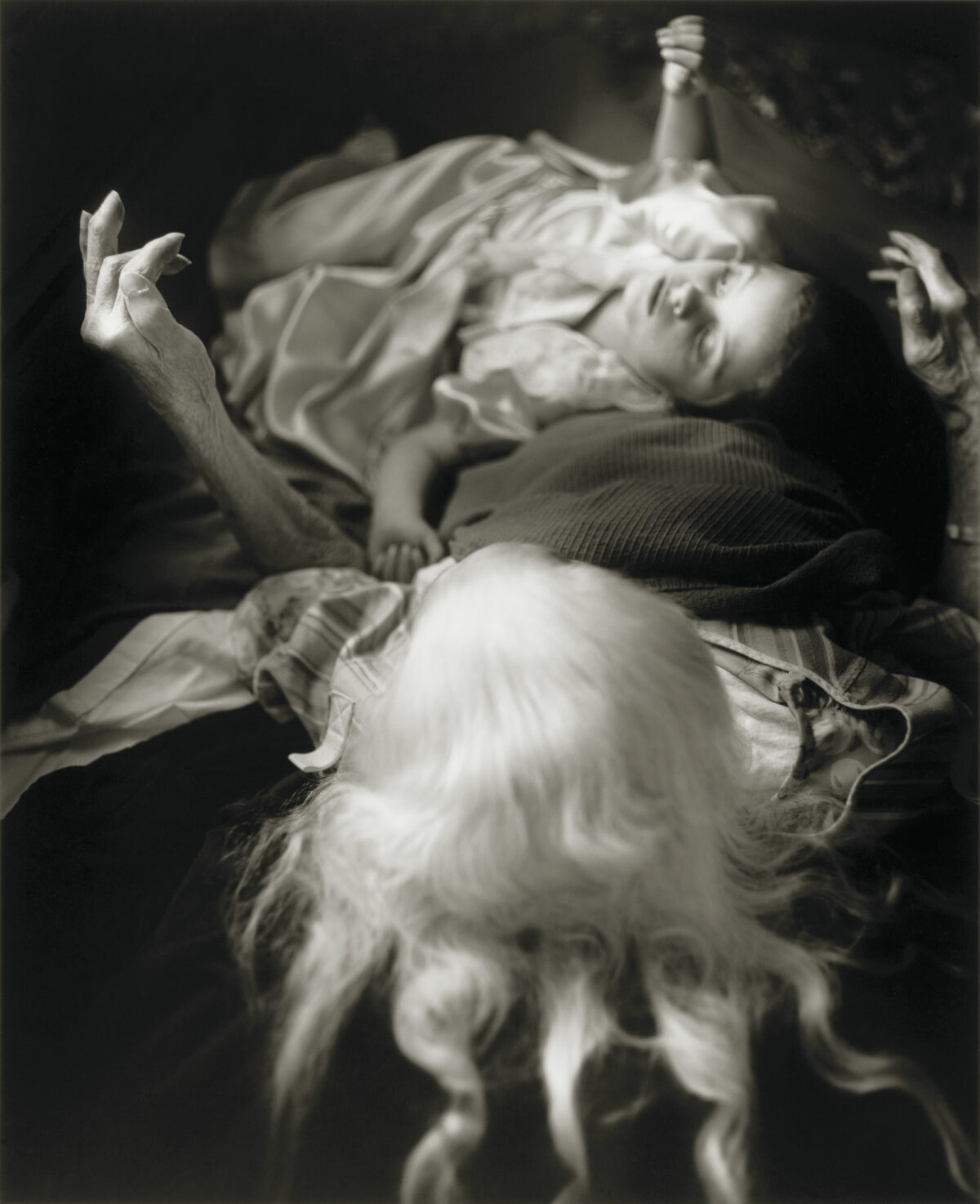

Sarah Meister, curator, Department of Photography, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Dorothea Lange is rightly heralded for her attention to the human condition, which was matched by a lesser-known concern for the environment. Lange captured the devastation wrought by the exploitation of natural resources most memorably in her series Death of a Valley (photographed in 1956 with Pirkle Jones on the eve of the construction of the Monticello Dam to provide irrigation for neighboring valleys in Napa County). In another striking example of work that speaks to the environment, one grasps the impact of the Dust Bowl on the worn lines of this cotton picker’s hand. The photograph will be featured in Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures, on view at MoMA from February 9 through May 9, 2020.

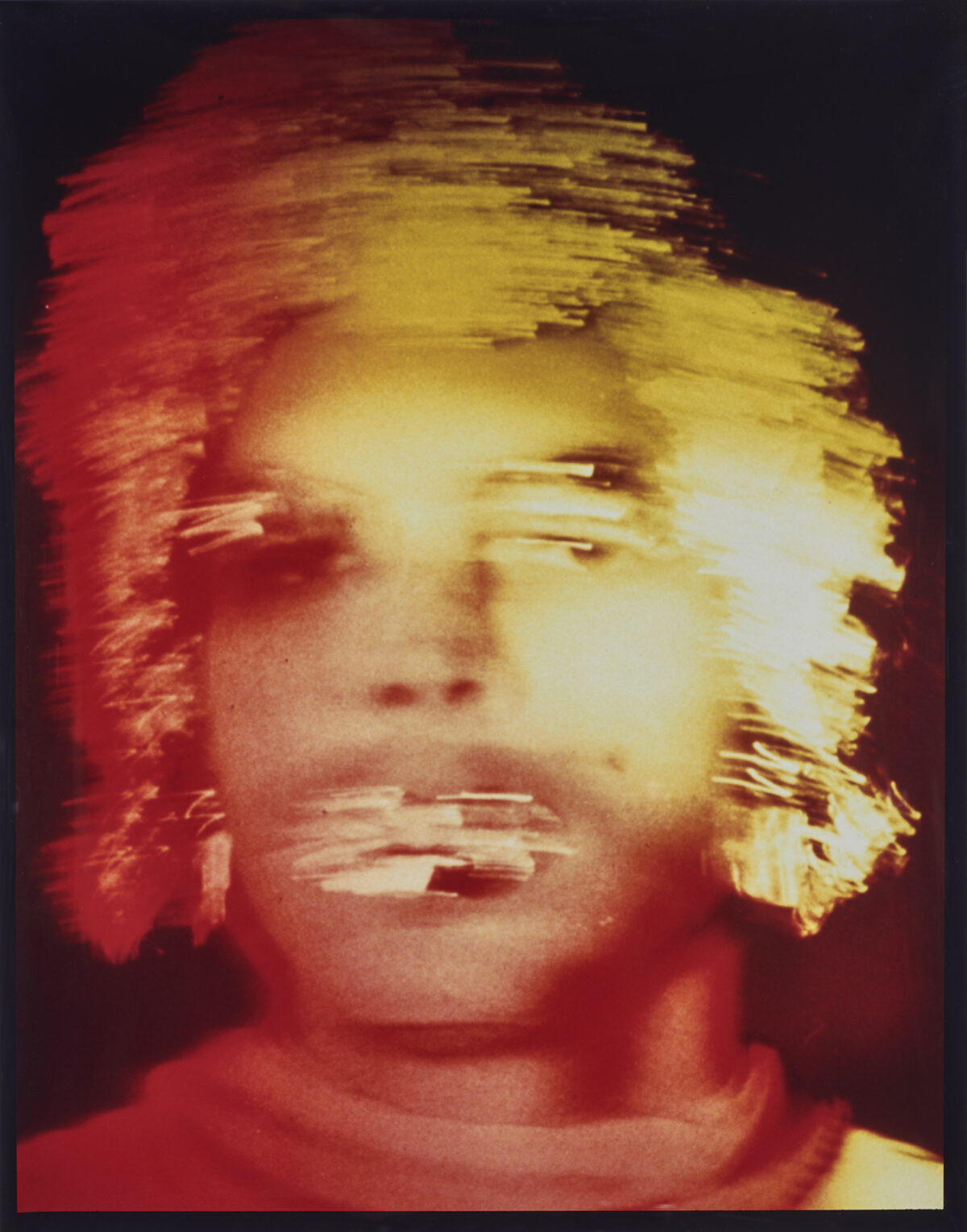

RongRong, photographer and co-founder and art director of Three Shadows Photography Art Centre

To continue his explorations of the landscapes of the natural world, Chinese artist Shao Wenhuan was invited to Switzerland for a three-month residency. By assembling numerous focal points into a single image that seems to conform to perspective, Shao hides hundreds of moments in one image.He always intervenes in his images using multiple artistic methods such as paint strokes, cuts, abrasions, and stains, forming rich layers of natural and man-made details. In this work, Peaks, he drew a handmade white line. The scars of mechanical violence constitute a poetic satire, highlighting the direct and indirect damage to landscapes caused by interventions of human life and the resulting acceleration in natural-resource extraction.

Touria El Glaoui, founding director of 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair

I first saw this print at the 2019 London edition of the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair. Louisa Marajo is an artist from Martinique, and her work responds to the sargassum (algae) blooms that have swamped the island. Its unprecedented growth is attributed to human activity. As sargassum dies and decomposes, it releases hydrogen sulfide and blocks the sunlight, causing other organisms to suffocate, devastating the ecosystem. Marajo takes an image of her seemingly anarchic installations, made by cut wood, construction pallets, and photographs of sargassum that she cuts and sticks onto these materials, adds bits of color from a “warning-tape” palette, and then lays on top of it a single photograph of sargassum.

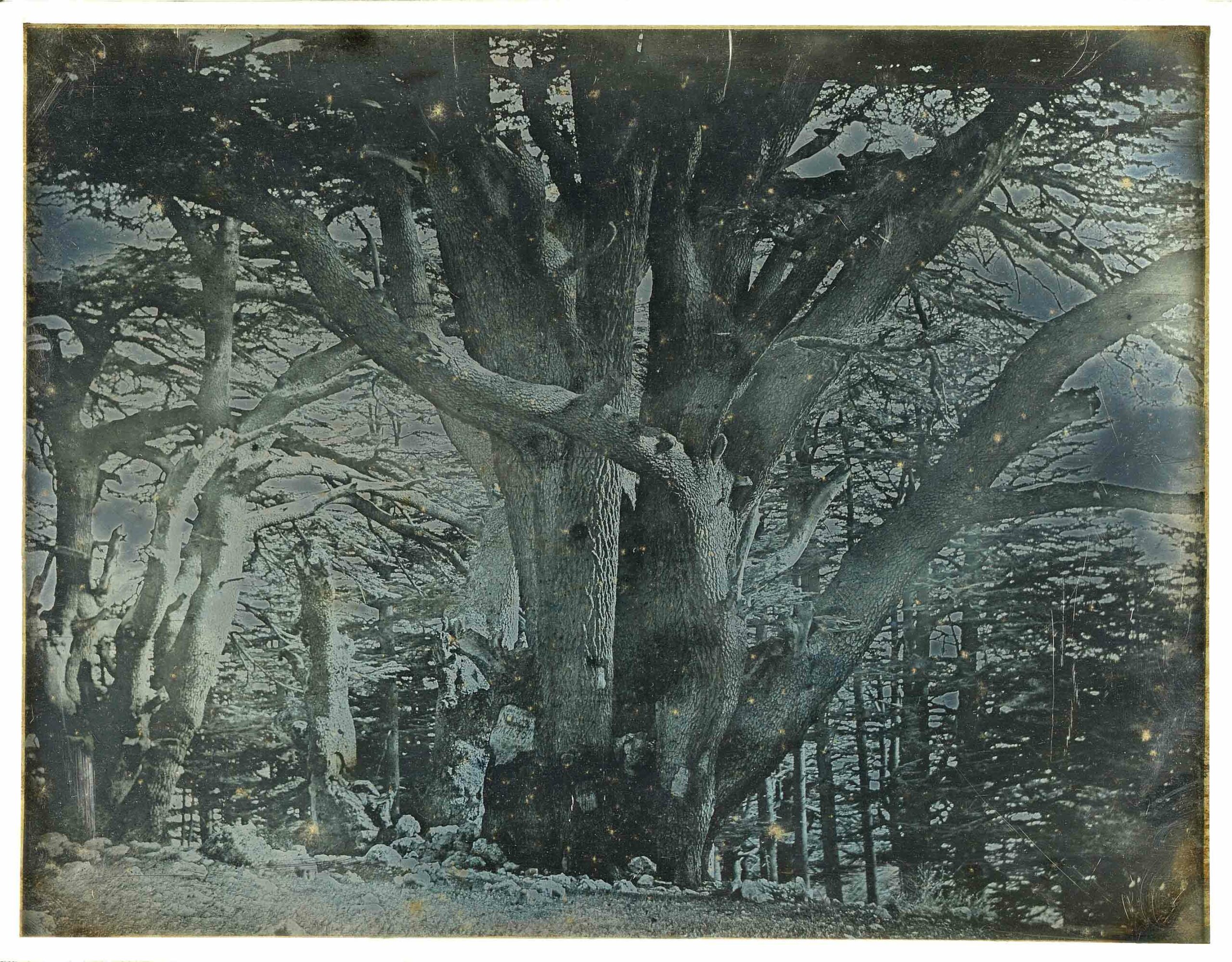

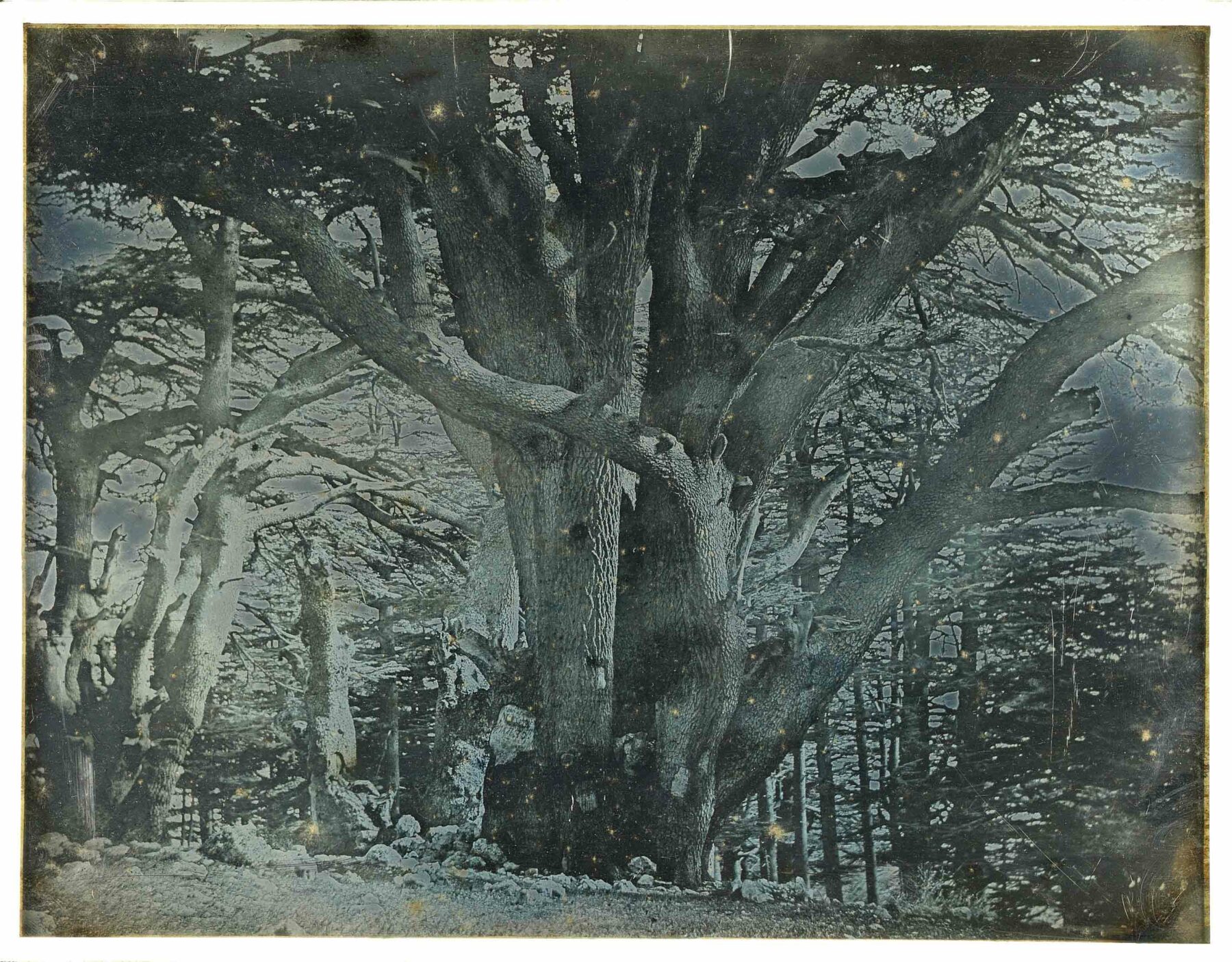

Stephen Pinson, curator in the Department of Photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Some of the most evocative images in Monumental Journey, the exhibition of daguerreotypes by Girault de Prangey that I organized at the Met in 2019, depicted trees. His view of the cedars of Lebanon, in which the trees seem to stretch on forever, is particularly haunting. Although they once covered large expanses of the mountains of the Near East, human depredation had confined the cedars to the western slopes of the Lebanon Mountains by the time Girault made this photograph. Today, the forests face their most perilous human-induced threat: global warming, which experts believe could wipe them out by this century’s end.

Emma Bowkett, Director of Photography, Financial Times Weekend Magazine

In 2017 I presented Katrin Koenning’s The Crossing as part of a group show for Triennale der Photographie in Hamburg. As with her decade-long, site-specific work at Lake Mountain, Koenning’s work captures ecological fragility and charts the destructive impact of climate change on the environment and community. I see this ongoing project as a love letter to Mother Earth, Koenning returning again and again to bear witness, drawing us into the narrative, reminding us of her vulnerability but also her strength. The land is part of us – our souls, our flesh, our hearts. We are obliged to respect it.

Paul Moakley, Deputy Director of Photography and Visual Enterprise, Time

I’ve always admired the simple genius of Charles Darwin working in his garden with just a magnifying

glass. I’ve read that he even put his kids to work recording the details of the natural world outside

their home. All of this intense looking added to making radical discoveries in his groundbreaking

work, Origin of the Species.

Stephen Gill’s monograph The Pillar (Nobody Books) is a series of photographs looking at birds

(and one fox) in a field near the artist’s new home in Sweden. Gill employs an inexpensive digital

camera with a sensor that reacts to the birds landing on a wooden pole he installed. The result is a

wonderous, intimate, and immediate sense of seeing nature, one that often feels distant in our lives

among people.

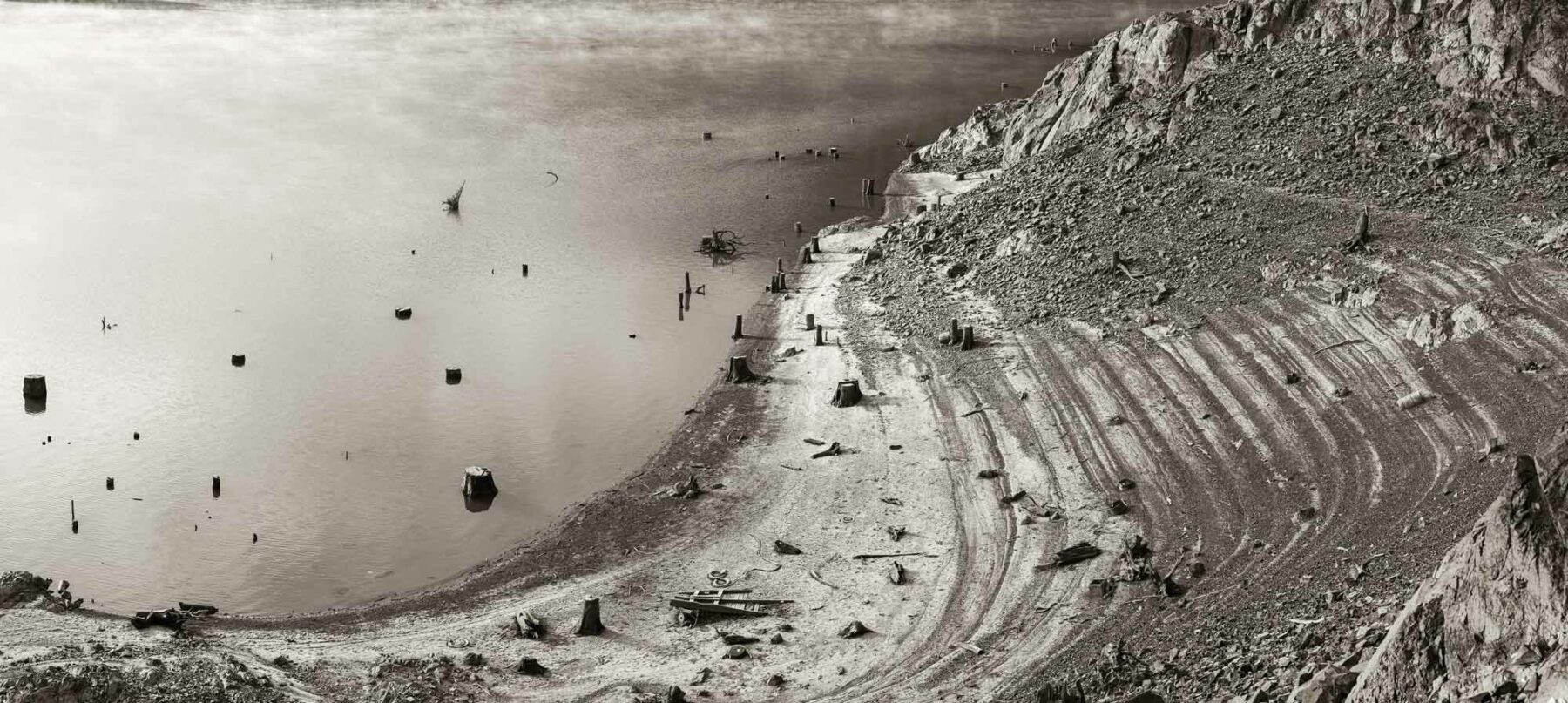

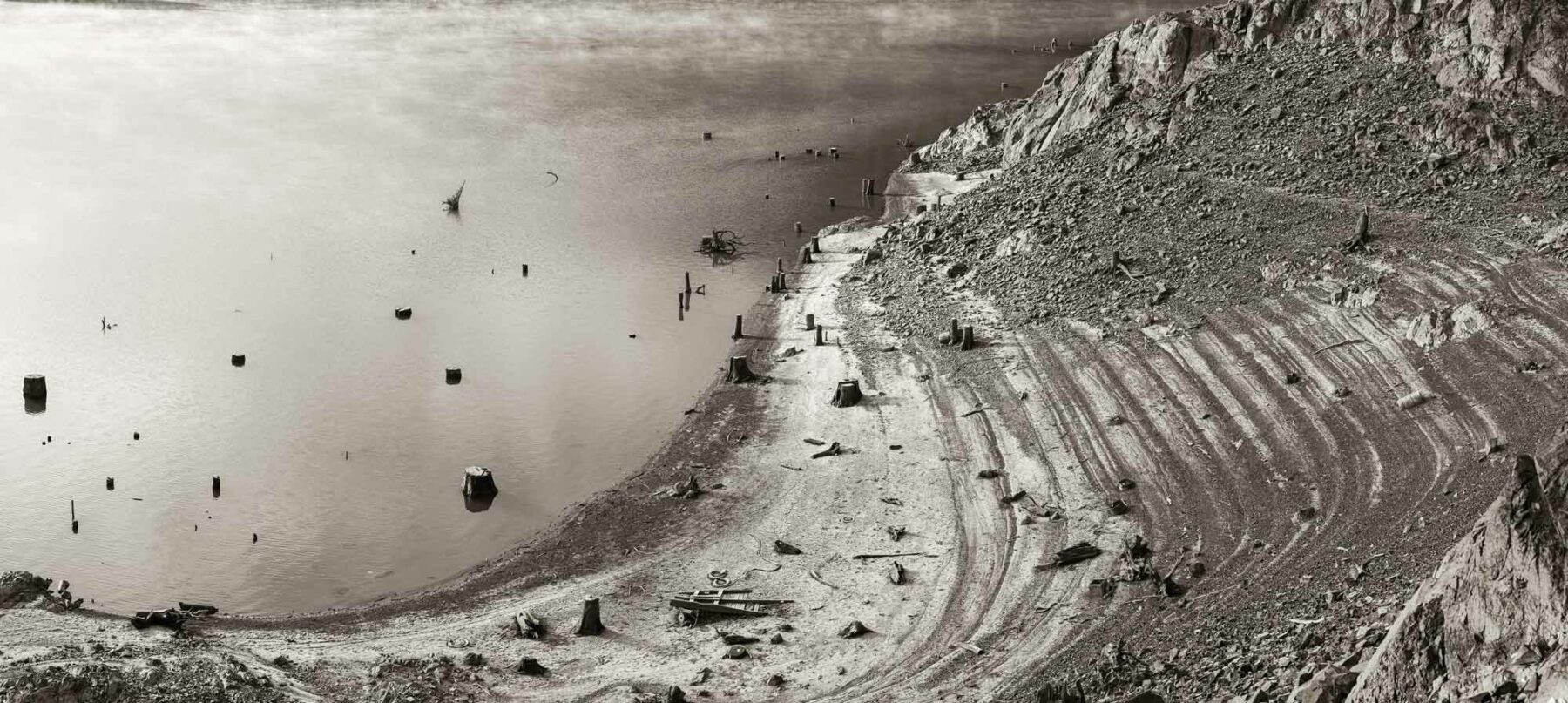

Michelle Dunn Marsh, publisher of Minor Matters Books and chief strategist at Photographic Center Northwest

The tenets of Minor Matters were partially informed by my awareness that trees often die so books can live. Through a lifetime of seeking the elusive visage of Tahoma (Mt. Rainier), and seeing Louwala-Clough (Mt. St. Helens) emitting its ash cloud in 1980, I have experienced nature as fragile and as fierce. How best to live, respecting both qualities? Joe Freeman’s photograph holds those elements, and many others, in an uneasy scale. It reminds me to continue to minimize the detritus of my life, to balance the fact that I have consciously chosen, over a lifetime, to leave behind many books where trees once stood.

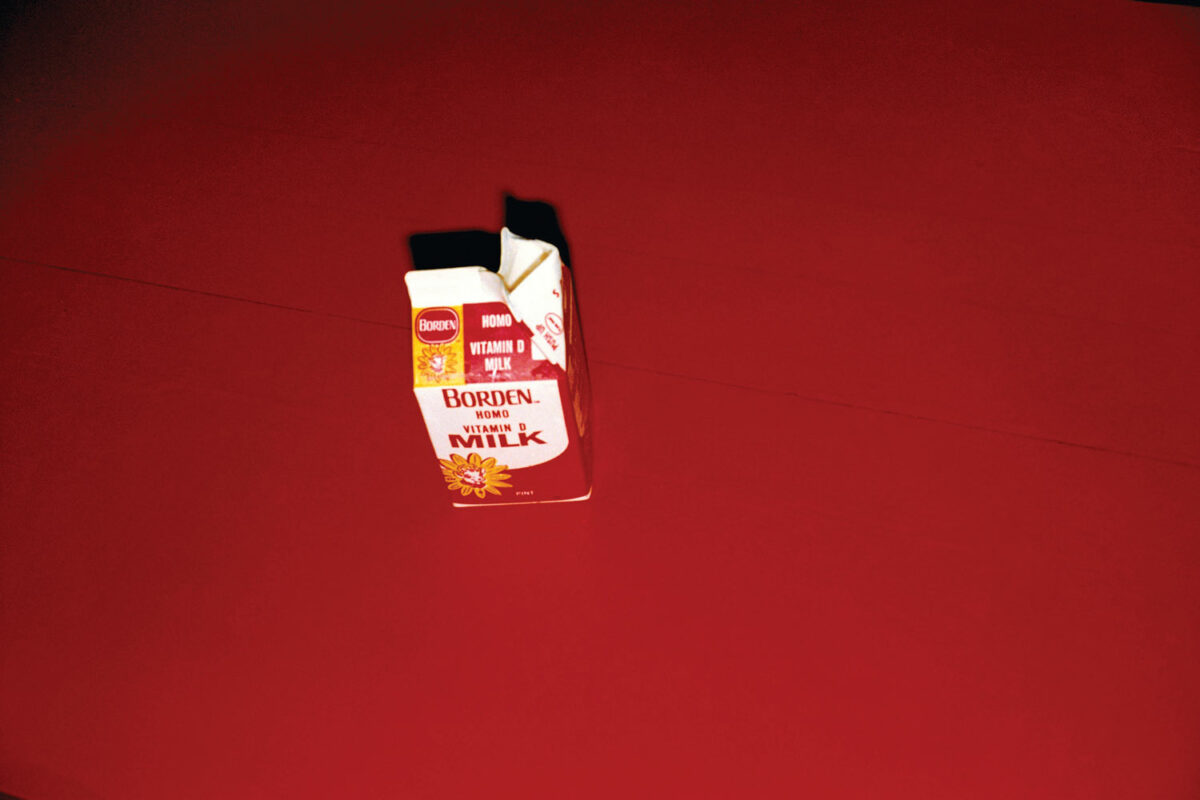

Drew Sawyer, Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian Curator of Photography, Brooklyn Museum

At the center of Allan Sekula’s modest survey at Marian Goodman Gallery last summer, regrettably the artist’s first solo exhibition in New York, was Waiting for Tear Gas [white globe to black] (1999-2000), a slideshow of 81 photographs that he took during the 1999 World Trade Organization protests in Seattle. The tens of thousands of anti-globalization demonstrators, who gathered to peacefully condemn the support of corporate interests over environmental and social concerns, were met with police violence and media ridicule. Sekula’s images, however, reject the style and tools of photojournalism, which tend to sensationalize and universalize events, in favor of the banal and often boring realities of activism and politics. And like political action, his images are slow and demand our time – if only we had more of it now.