If there is one medium over which the photographer Sally Mann has total command, it is the written word. She is a superb writer, having learned well from her favorite authors and poets, Nabokov, Faulkner, Welty, Rushdie, Eliot, and Pound. Her particular gift is metaphor. Here, for instance, is Mann describing the drying blood on the frozen ground after a convicted sex offender who had escaped onto her farm was shot, killed, and hauled away: the blood puddle “shrank perceptibly, forming a brief meniscus before leveling off again, as if the earth had taken a delicate sip.”

How can any photograph compete with a metaphor like that? But this very task – using photography as an instrument for metaphor-making, for connecting one thing to another, across lines of time and race and through the space separating the living from the dead – seems to be a large part of what Mann has aimed to do in the 40-plus years of her photographic career, a career that’s now being celebrated with a retrospective curated by Sarah Greenough of the National Gallery of Art and Sarah Kennel of the Peabody Essex Museum. Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings is at the National Gallery through May 28 and the Peabody Essex from June 30 through September 3, after which it travels through January 2020.

In her earliest family photographs, Mann’s suggestive titles made the metaphors for her; they added extra meanings to her already suggestive pictures. Indeed, this may be one reason that her photographs of her three children, Emmett (who died two years ago), Jessie, and Virginia, sometimes nude, sometimes clothed, raised such a ruckus. The Perfect Tomato (which is not in the show) might have passed as just a sun-bleached portrait of Mann’s daughter Jessie pirouetting nude on a table with a few tomatoes gleaming darkly in the foreground, if “tomato” weren’t slang for a ripe and luscious girl (an expression Mann says she didn’t know). Likewise, if the photograph of Virginia resting near the river’s edge, The Alligator’s Approach, had been named to make it clear that said alligator was actually plastic, the picture might not have seemed so ominous.

But Mann likes pushing the envelope, especially when there’s a nice juicy metaphor to be had. And what’s more, she likes to make it seem as if the envelope were pushing her, as if forces beyond her control were calling the shots. In the 1990s, once her children started growing up and moving out of the house, she turned her lens on the land around her, creating soft, almost romantic photographs of the southern pastures, bridges, rivers, trees, and hills in Virginia. Minimizing her own agency, she described this period of her work in the catalogue: “The kids seem to be disappearing from the image, receding into the landscape … I have been ambushed by my backgrounds.”

She was smitten by the southern landscape, and you can see why. In one photograph of the Blue Hills, which she carefully printed in order (as Mann once quipped about her family photos) to “out Ansel the most meticulous Adams,” you see layers upon layers of soft hills, lighter and lighter and lighter tones of gray, moving up toward the horizon line until, at some indecipherable point, they merge with the pale sky. It is a lush and lovely image. Another gorgeous photograph shows the river, smooth as velvet, flanked by spiky dark grasses and voluptuous dark trees. Here, as in her family photographs, Mann, far from being controlled, is in full control of her medium.

But Mann hasn’t always wanted full control. As she got older, she began to court accidents, hoping that some of the deeper, darker truths of the Southern landscape – hidden meanings, connections to slavery, race relations, and the Civil War – might seep through. Somehow she wanted to connect her own privileged white existence in Lexington, Virginia, where her children played on their rugged, beautiful farm and in their lazy river, to the darker history of Virginia and the South. But it’s not as if the bodies of Civil War soldiers are still around. It’s not as if the sweat and blood of slaves are still evident. The earth, to alter the words of Mann herself, has taken a giant gulp, swallowing all visible evidence of its terrible history.

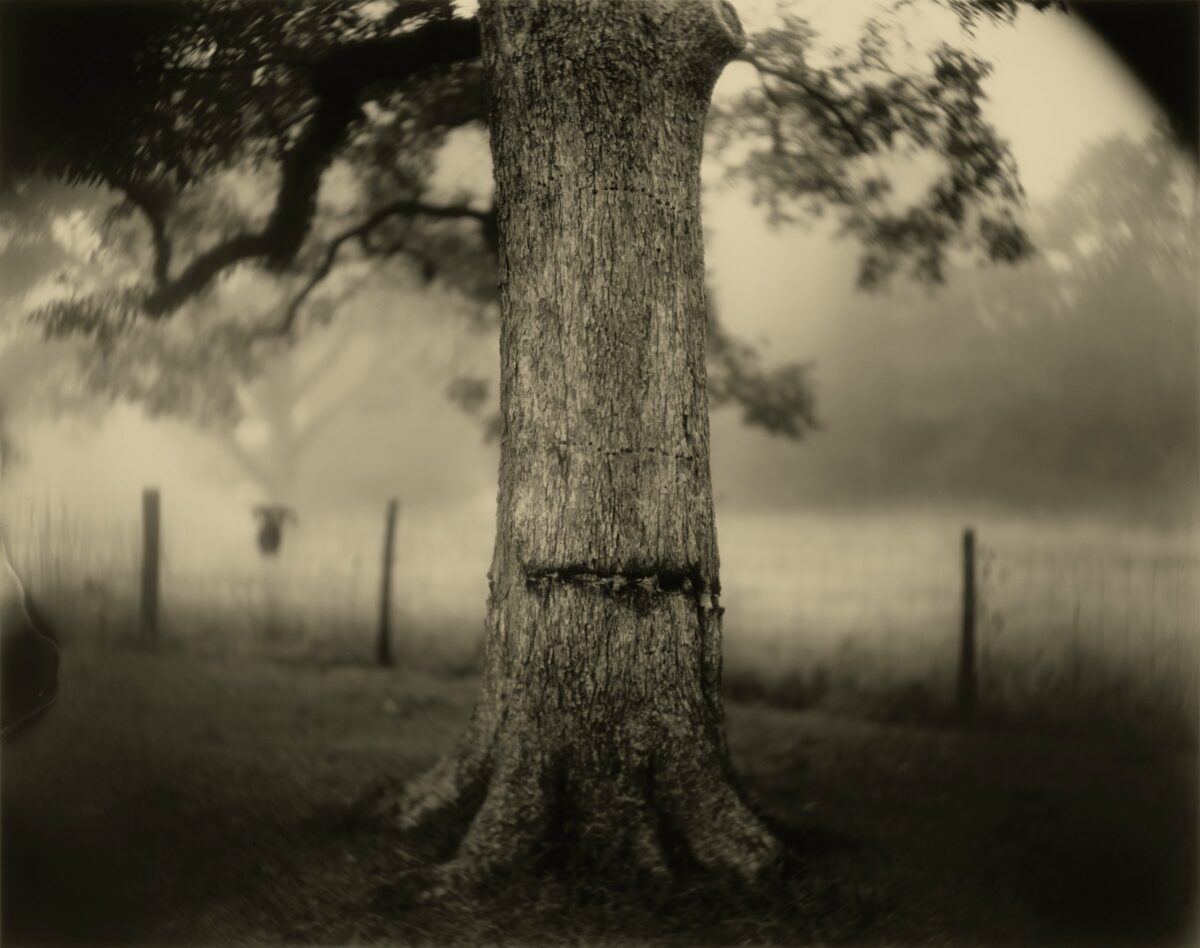

For the photographs collectively titled Deep South, which focus particularly on Mississippi, Mann used an 8-by-10-inch view camera and a beat-up antique lens. She used high-contrast Ortho film and processed her photographs with deliberate carelessness. When the prints came out somewhat weird and irregular, with chemical drips, slashes, tracks, and flares of light, she was pleased. Somehow, these imperfections could be read as metaphor, as the ragged and violent history of the South impressing itself on her photographs.

Consider Mann’s handling of the murder scene of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African-American boy from Chicago who was killed in Mississippi in 1955 and dumped into the Tallahatchie River with the fan from a cotton gin tied to his waist. (Mann was moved enough by this event, which happened when she was a child, to name her son Emmett.) In 1998, some 43 years after Till’s murder, Mann approached the riverbank where Till’s body had been hauled out of the river. To bring out the latent brutality there, she went against the rules of photography and shot a dark gash in the riverbank straight into the sun. In a photograph of the bridge from which Till’s body was dropped, she photographed a faint, delicate structure of light crossbars and a line in the water indicating, perhaps, a splash, but it tells nothing concrete about this crime. Only if you know what happened here would you think, as Sarah Greenough did, that a “seemingly careless chemical streak evokes a teardrop.” The wished-for chemical accident leaks a tiny drop of truth, but only if you already know the truth you’re looking for.

Around 2000, when Mann started photographing Civil War battlefields, she communed with the 19th century by using a 19th-century photographic process. In these works, collectively titled Last Measure, she showed her full devotion to the dead by once again courting mistakes, praying, “Please don’t let me totally screw it up, but still …. screw it up enough to make it interesting.” She used an old camera, a faulty lens, and large taped-up glass plates onto which she had slopped some collodion.

The resulting photographs are the largest and most mysterious of Mann’s landscapes. One, taken at a cornfield in Antietam, is shot low to the ground, giving us the angle of a dying soldier. In the darkness you can see some grass in the foreground and some vaporous forms rising from it. While much of the moodiness has to do with Mann’s willful mistakes – fogging, flares, light leaks – than with Antietam itself, her near-abstraction does evoke, as she wished, something of the hushed and mournful air that the dying soldiers might have breathed at night in 1863. It helps to be reminded of Abraham Lincoln’s comment that the number of deaths was so devastating that “the Heavens may almost be said to be hung in black.”

Maybe it was inevitable that at some point Mann would come back around to herself and her place in the South’s history of racial injustice. After all, Lexington, Virginia, was not only her family’s home but that of the black nanny who raised her, as well as the final resting place of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, and also home to countless black people she never knew: “I had always seen, but not seen, black men on the fringes of white life, mowing, tending bar, or waiting for work in the shade of the big trees at the courthouse,” Mann is quoted as saying in the catalogue. Who were they?

In 2006, Mann began asking black men – kitchen workers, law students, laborers – if she could photograph them. Her photographs, which are moody, large, out-of-focus, and quite beautiful, made me a little uneasy. After all, she took these pictures to make things right for herself; she didn’t actually right any social wrong. These men were never invisible to themselves, only to her.

In the end, Mann’s most affecting racial reckoning was done retroactively, with old photographs. Once she began to see her own role in the South’s racial history, she found the nexus of it in her family’s long relationship with their beloved nanny, Virginia Carter, known as Gee-Gee, the granddaughter of a former slave, who not only raised Sally and her brothers but six of her own children, whom she supported with 12-hour work days followed by nights of ironing. After Gee-Gee died in 1994, Mann began to ask some tough questions (printed on the exhibition wall labels): “What were any of us thinking? Why did we never ask the questions? That’s the mystery of it – our blindness and our silence.” Her family simply accepted this arrangement: “Nothing about it seemed strange, nothing seemed wrong.”

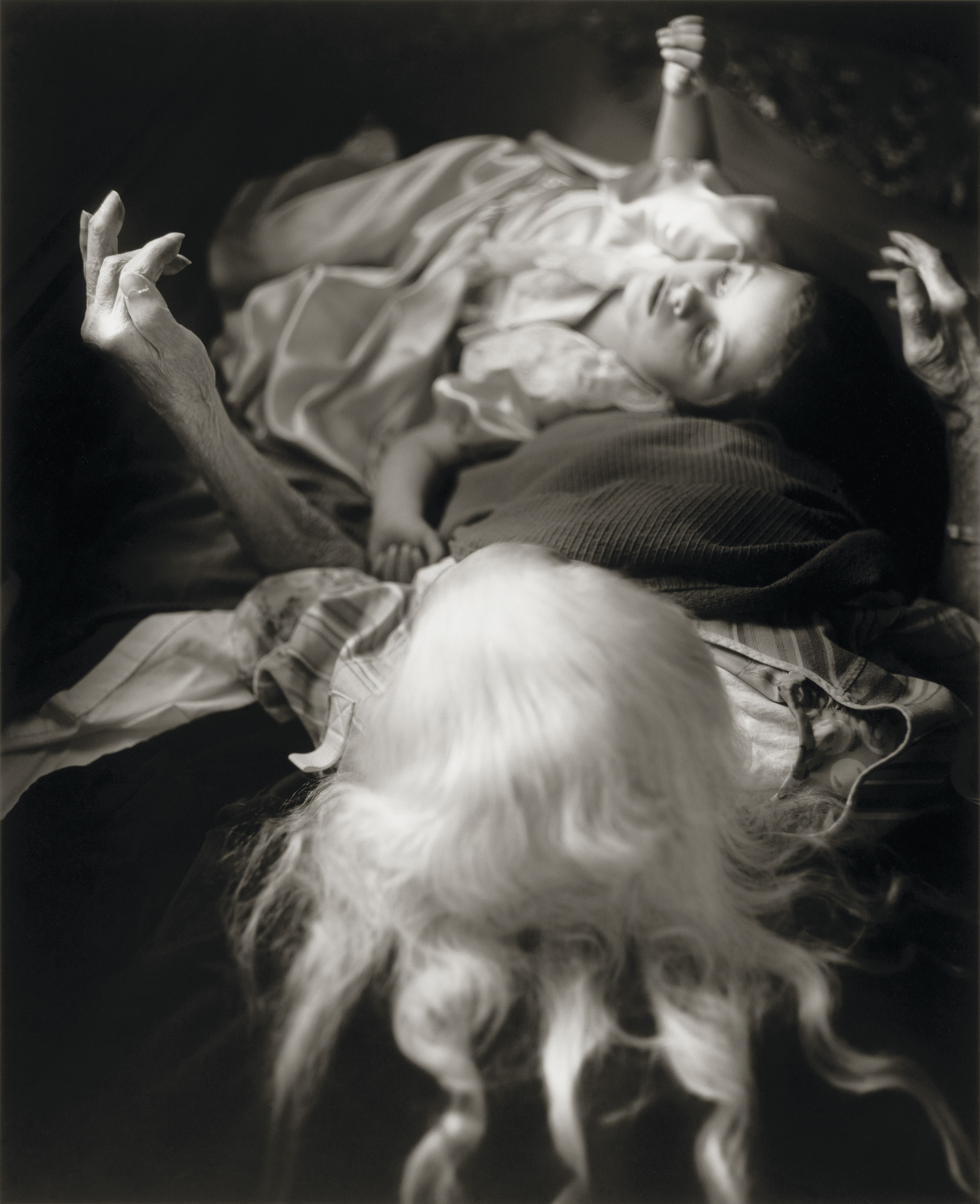

It takes a brave soul, which Mann is, to look for the darkness underlying her most beautiful pictures. Mann’s photographs of the two Virginias – Sally’s nanny, Virginia (Gee-Gee), and her daughter Virginia (named after Gee-Gee) – touchingly contrast the bodies of two persons who are unequal in just about every way possible. One picture, for instance, focuses on the feet. Little Virginia’s two tiny, young white feet, pliable, soft and relaxed, frame and enclose Gee-Gee’s large spotted legs and crooked, cracked, working feet. Another shows the two Virginias at rest: Gee-Gee’s white hair is swirling out in the bottom of the frame; on top is little Virginia, who rests on the unseen body of Gee-Gee. Both hold their arms out and up, as if “jointly conducting an unseen orchestra,” Greenough writes.

Who would question the love in such a photograph? Well, Sally Mann would: “Down here you can’t throw a dead cat without hitting an older, well-off white person raised by a black woman, and every damn one of them will earnestly insist that a reciprocal and equal form of love was exchanged between them.” But how could it be? How, Mann asks in the catalogue, could “the feelings exchanged between two individuals as hypocritically divided ever have been honest…?” Once again, Mann lets her words do the heavy lifting, while her pictures remain free to be beautiful.