About 15 years ago, I came across Fazal Sheikh’s slim book A Camel for the Son (2002), and I couldn’t put it down. The black-and-white portraits of Somali refugees in Kenya – mostly women and their children – were as stunning as they were rich in humanitarian content. Having made a harrowing journey to the refugee camps, the women in his photographs faced further hardships once they arrived – illness, hunger, rape, threats of violence – simply by virtue of the fact that they were women. The title of the book was taken from a story Sheikh was told by Abshiro Aden Mohammed, the Women’s Leader in the Somali Refugee Camp in Dagahaley, Kenya: when a son is born, the family is presented with the gift of a camel, so that when he is grown the camel will have sired many litters, and he will be prepared for adulthood. But when a daughter is born, the family receives nothing, and she stays home while her brothers go to school.

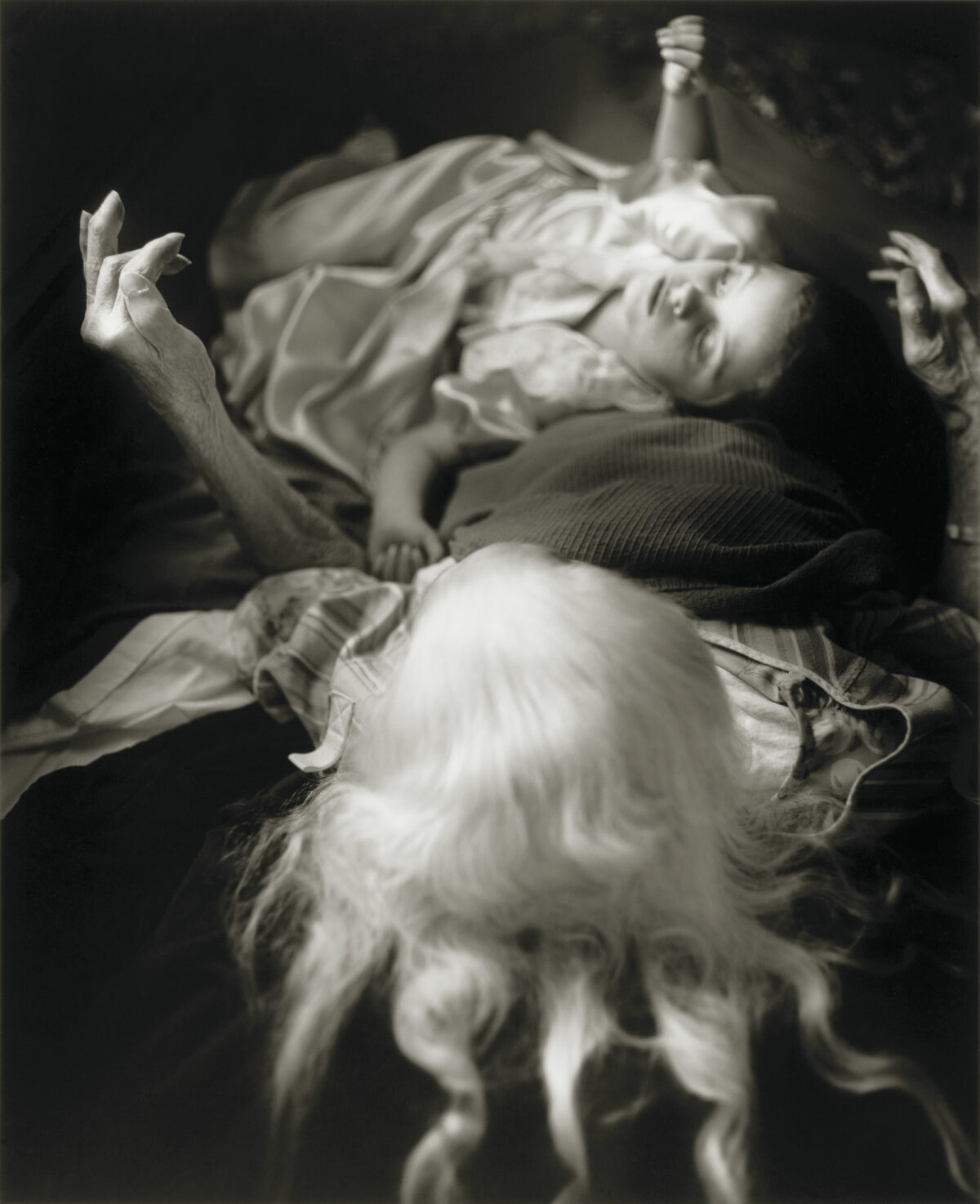

Sheikh often photographs women – frequently the most disadvantaged segment of an already disadvantaged population – but he avoids many of the conventions of what is known as concerned photography. In A Camel for the Son, rather than documenting evidence of desperate hunger or inadequate shelter, he made beautiful portraits of mothers with their children swaddled in their laps, or nursing. The women gaze directly at the camera, or down at their children. My eye was drawn, again and again, to the hands in the pictures, resting in gestures of protection and affection. In one image, a grandmother holds her grandson in her lap, her wrinkled hands clasping him tight. His small hands are open and relaxed, as if he feels safe in that moment.

According to the United Nations Refugee Agency, at the end of 2015 the number of displaced people had reached 65.3 million globally, with 21.3 million refugees, half of whom are under the age of 18. How to locate the individuals at the heart of these wrenching global disruptions? Sheikh’s portraits render his subjects as something other than victims, or symbols. They are people with names, with specific histories and stories, and with their own particular pain.

Kenya, Somalia, Afghanistan, India, Brazil, Mexico, Israel, and Palestine are just some of the places where Sheikh has photographed displaced or disadvantaged populations. Portraiture is the thread that connects his projects, though his landscapes and photographs of ruins give evidence of displacement as well. Clearly collaborative in nature, his portraits are meditations on the ethical possibilities of portraiture in the context of political turmoil. How can a photographer operate within a conflict zone or a refugee camp and make work that doesn’t create more distance or a greater degree of otherness? Without getting into the weeds of the ethical debates about much of the photographic coverage of refugees, suffice it to say that such images can be necessary while also being problematic. We – viewers fortunate enough to be in a conflict-free part of the world, for now – tend to respond to these pictures with a vague sense of pity. This is not the reaction elicited by the subjects of Sheikh’s photographs, who resolutely hold our gaze.

The recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship in 2005 and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2012, Sheikh often includes personal narratives, found photographs, maps, and historical material to provde context, opening up a space between fine art photography and photojournalism. His formal portraits give his subjects the power to confront the camera, the photographer, and by extension the viewer, with a sense of agency and individuality. “In most of his photographs,” says Eric Paddock, curator of photography at the Denver Art Museum, “you’re looking right into the subjects’ eyes, and they’re looking right back at you. The idea of cultural, racial, ethnic, or economic difference kind of dissolves. You recognize that regardless of circumstance, everyone has the same hopes and desires, and that’s something his pictures really connect us with.”

More than 100 of Sheikh’s photographs are on view from August 13 through November 12 at the Denver Art Museum, where Paddock has organized the first comprehensive museum exhibition of his work in the U.S., Common Ground: Photographs by Fazal Sheikh, 1989-2013. Meanwhile, Homelands and Histories: Photographs by Fazal Sheikh is on view through October 1 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. The 75 photographs were acquired with a grant from Jane P. Watkins and selected by the MFAH’s curator of photographs, Malcolm Daniel, in collaboration with the artist.

In addition to exhibiting in museums and galleries (he’s represented by Pace/MacGill Gallery in New York), Sheikh works with nonprofits and human-rights organizations to make his work as accessible as possible. He has made a number of his books available free of charge and in multiple languages (A Camel for the Son has been translated into Somali, for instance); he produced Beloved Daughters (2008), a set of 30 posters, with the Open Society Foundation. The posters were drawn from two series: Moksha (2005), about a community of widows in the holy city of Vrindavan, India, and Ladli (2005), which focuses on the plight of young women in India under traditional Hindu law. One thousand sets of the posters were distributed to various institutions in India, including women’s rights organizations and universities. The images in Ladli range from a portrait of a tiny newborn, eyes closed, at an orphanage, to small girls who are rose sellers or rag pickers, to young women living in a shelter. All of them (with the exception of the sleeping baby) look straight into the camera. Sheikh often heightens the intensity of their gaze by focusing on their eyes and allowing the rest to fade out of focus.

Sheikh was born in New York City to an American mother and a Kenyan father. He attended Princeton, where he studied with Emmet Gowin, whose influence can be felt, if not in his choice of subject matter, then in his restrained, collaborative approach to portraiture. One could point to other affiliations – Malick Sidibé comes to mind, as does the Heber Springs, Arkansas, studio photographer Mike Disfarmer. But Eric Paddock also sees a connection with a little-known 19th-century Swiss photographer, Carl Durheim, who was commissioned by the government to photograph hundreds of stateless people. The connection, says Paddock, is not to the regulatory aspects of Durheim’s project, but to the idea of the photographer as a documentarian of people who would never have normally had their photographs taken. Sheikh’s photographs are a form of recognition, acknowledgment, and attention, when it often seems that the rest of the world, out of fatigue and helplessness, is turning away.

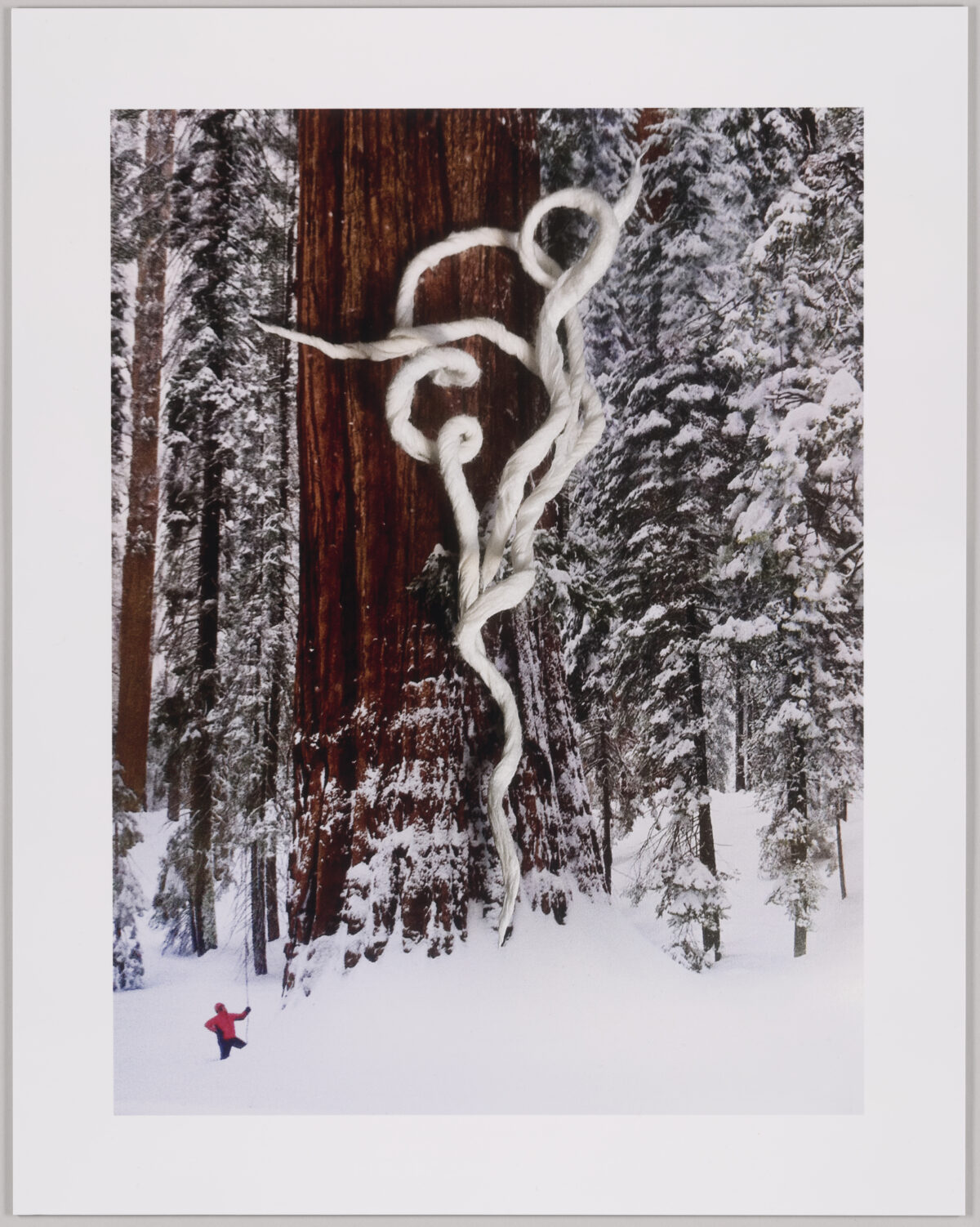

In 2010, Sheikh was invited by photographer Frédéric Brenner to participate in This Place, an expansive project involving a dozen photographers making work in Israel and the West Bank. His resulting book, The Erasure Trilogy (Steidl, 2015), won the 2016 Kraszna-Krausz Best Photography Book of the Year award. In this three-part series, Sheikh began with the ramifications of the Arab-Israeli War of 1948, observing that the war “left a wound that has never healed.” The project includes images of ruins, including scarred landscapes and fragments of buildings, as well as portraits and family photographs, and aerial images showing that the alteration of the Negev desert has often coincided with violence against the Bedouins who were living there. As the project’s title suggests, the images draw attention to what is being erased – villages, relationships, histories, a sense of belonging to a place.

In the third part of the trilogy, Sheikh returned to his use of portraiture to personalize large and often complicated social issues. Independence | Nakba, consists of 65 black-and-white diptychs – one for each year from 1948 to 2013 – pairing people from both sides of the conflict. The entire series was on view last year at Pace/MacGill Gallery, exhibited in pairs that stretched in a long line along the gallery walls, reflecting the ongoing nature of the conflict over generations. Viewers did not necessarily know who was Israeli and who was Palestinian, which may be the point. We are asked to contemplate the differences in their experiences, while also being acutely aware of their shared humanity – the ultimate message, boiled down to its essence, of Sheikh’s ongoing photographic endeavors.