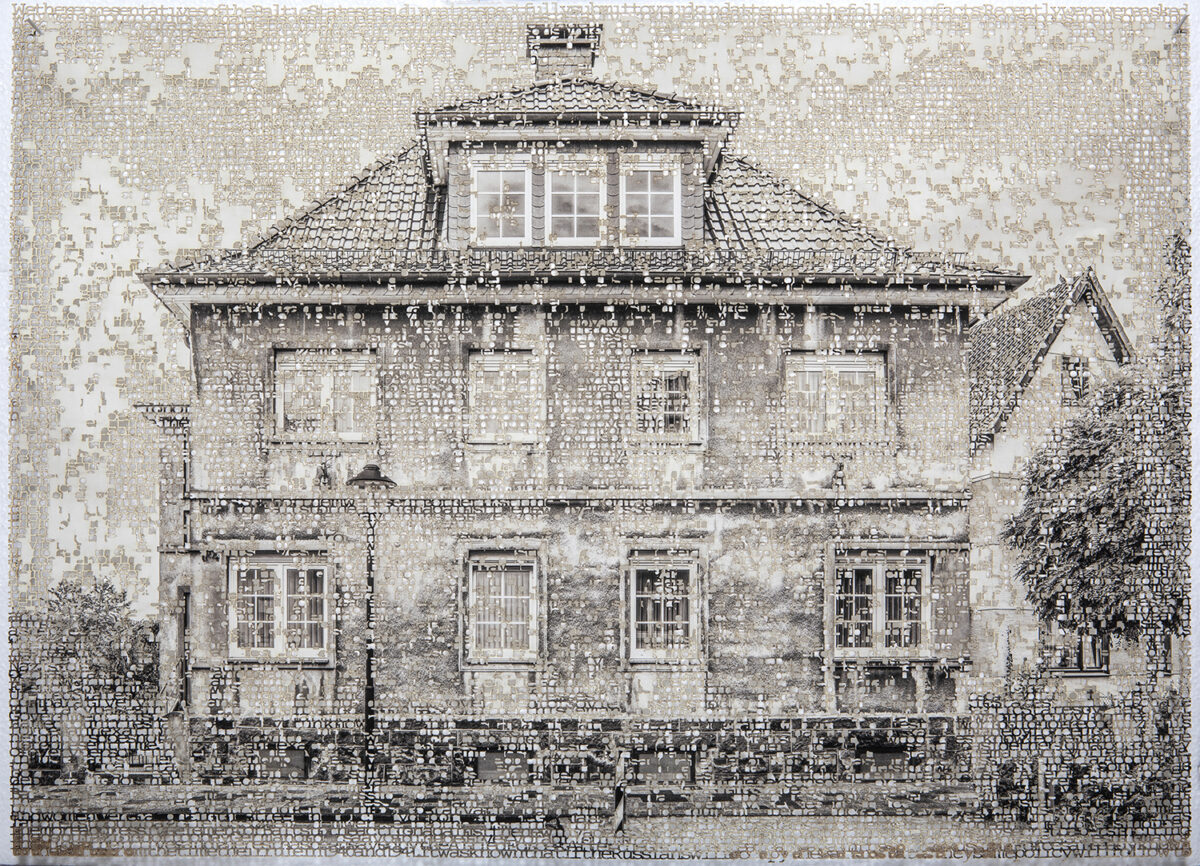

Michelle Dunn Marsh, the founder of Minor Matters, the Seattle-based photography book publisher, has championed many photographers over the years, curating, editing, and shepherding their work into exceptional photobooks and exhibitions. Now, Dunn Marsh (who was the subject of a profile in photograph’s May/June 2018 issue) is publishing her own book through Minor Matters: Seeing Being Seen: A Personal History of Photography, which can be pre-ordered here. The book is a memoir of sorts, in which photographs that she lives with (by Will Wilson – who made the book’s cover image – Endia Beal, Stephen Shore, Paul Strand, Carrie Mae Weems, Eugene Richards, Mary Ellen Mark, Sylvia Plachy, and others) anchor and illuminate key moments in her life. I spoke with Dunn Marsh and photographer Sylvia Plachy, about photography, friendship, seeing, and being seen.

All images from Seeing Being Seen, Minor Matters (anticipated release, fall 2021).

Jean Dykstra: Michelle, can you talk about the origins of the book? It began with an exhibition at Seattle’s Highline Heritage Museum in the summer of 2019, right?

Michelle Dunn Marsh: Correct. I’ll be honest, I was very resistant to doing anything about me. I’m always happy to do things for photography and about photography, but the museum’s desire that this reflect a personal viewpoint and not a curatorial viewpoint was really uncomfortable. But with the prodding of the museum’s executive director [Nancy Salguero McKay], I did it. The idea of sharing what I had learned from my life, from the incredible people that I’ve had the opportunity to get to know and work with, felt important. And I make books, so the natural inclination after the exhibition closed was: I wonder if this can be a book?

Sylvia Plachy: It can! And it is!

Dykstra: You write in the book that you did it in part for the benefit of other shy girls, who might see some aspect of themselves in your story. I think it is important to show younger people, and particularly young women, a little bit of how you got to where you are, because when you’re at a certain point in your career, it can seem that you were just born to it, that you always had this knowledge and this clout. It’s helpful for people to see the twists and turns along the way.

Dunn Marsh: Exactly. There are moments – and certainly the recent re-establishing of the military government in Myanmar [formerly Burma] was one of them – when the reality of the familial molecules that form who I am strike me. Like standing in the pub in Thomastown, Ireland, the structure where my paternal grandmother was born, or thinking of my mother coming alone to Seattle after Burma’s military coup in 1962. And then my reality is this quite idyllic rural childhood, with access to some of the first Apple computers, and this life in photography. The shifts that can happen in a generation are sometimes monumental beyond belief.

But the book is also relevant because of the rise of photography. It’s become, in the last few decades, more important in the art world and subject to art-historical analysis. But that happened so quickly that the humanity of the experience I had – kind of growing up with a working connection with photographers – has shifted a little bit. So speaking about the photographs and the photographers from a place of humanity and accessibility feels important to me.

Dykstra: One of my favorite stories in the book is of you showing Stephen Shore a photograph of his in one of your art history books, when you were an undergrad at Bard, and thinking he’d be surprised to know that it was there.

Dunn Marsh: [laughing] Stephen was very quiet, and particularly kind in that moment. I never took a photo course at Bard, but I took the history of photography, at the recommendation of his wife [Ginger Shore, who I worked for in Bard’s publications office]. Stephen was the first person to participate in what became this five-year lecture tour through Aperture West, and if he hadn’t said yes, I don’t think it would have gotten off the ground.

Dykstra: How did you and Sylvia you meet?

Dunn Marsh: I was stalking Sylvia at an opening. Sylvia was very high on the wish list of photographers to lecture for Aperture West, so it was my job to try to convince her to say yes.

Plachy: It wasn’t easy. I don’t like talking in public. But she has been a big encouragement to me to keep talking. Like right now. She keeps dragging me into these situations and I have to sink or swim, so okay, here I am.

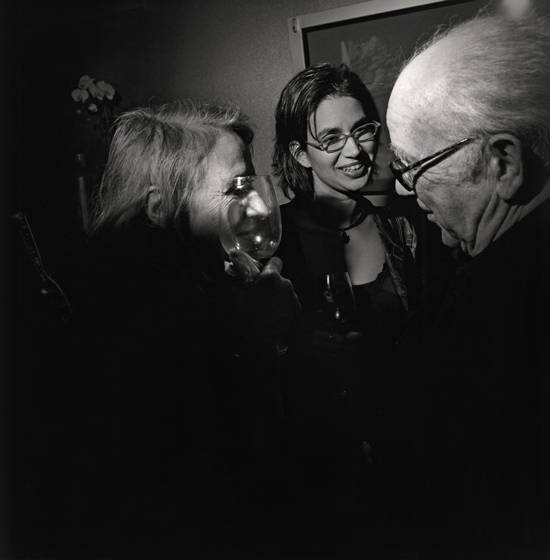

Dykstra: There’s a picture in the book of the two of you with Charlie Harbutt, taken by Larry Fink…

Dunn Marsh: That was at a book opening. Sylvia is holding a wine glass to her face.

Plachy: I’m hiding.

Dunn Marsh: And I kept saying, do you want some more wine?! What is happening?! And she said, I’m giving Larry a picture. Moments like that are a reminder of what a wonderful community exists because of photography. I keep a journal, so when I came home from parties like that, there would sometimes be these little snippets of lines that I’d write down.

Dykstra: I imagine those journals were quite helpful when you were doing this book.

Dunn Marsh: Yes, I still keep a physical paper datebook. I recently went back to 2003 to confirm something, and I became completely engrossed in how much I was doing then. It was making me feel a little bit ill.

Plachy: We were burning up! We were burning up like a comet, going too fast and speedily into life.

Dykstra: Can you tell me about the beautiful portrait of you, Michelle, wearing a coat, that Sylvia took?

Dunn Marsh: I was going through a divorce. It was not a good year, and I was trying to do things that I would not normally do, to confront some of my fears. One of the things I did was make a photograph with Adrain Chesser. I was lying on this wet sand, scared, nude, yet I felt so strong. When I saw the photograph, however, I realized how he had seen, and the camera had seen, a brokenness that was me at that moment. But I wasn’t feeling that. The interesting thing is the relationship between what happens with the camera, and the notions of truth.

So a few months later I was giving a lecture at Parsons, and I was toying with whether or not I would include this photograph in the lecture for grad students who I was trying to encourage to be brave, and take risks, and put everything on the line. Sylvia came to the lecture to support me. In the end I projected it for exactly three seconds, and after the lecture, Sylvia said: I’m glad you did that, but that’s not how I see you.

Dykstra: Sylvia, what did you mean by that?

Plachy: Well, I wanted to take some other kinds of pictures of her. So she came to my house. It was autumn, we were playing in the leaves, and she looked more the way I know her.

Dykstra: Portraiture is like that – what comes through depends on who’s looking. Hearing both of you talk about the nude, I see what you’re saying about the vulnerability there, but the first time I saw it, I read it as brave.

Plachy: But also, the setting is reminiscent of dying to me: the rocks, the leaves, it’s bluish, and so, it reminds me of death. Isn’t it interesting how many different ways we can see the same thing?

Dykstra: It sounds like the two of you have a very rich friendship but also a rich working relationship in terms of the feedback that you give each other.

Plachy: Yes, and it’s wonderful. We’ve been friends ever since that fateful trip across three cities for Aperture West.

Dykstra: Swan’s Way is another of Sylvia’s fantastic photographs in the book – can I ask about the picture, but also about you how you have it in your possession, Michelle?

Plachy: I was in Prague. I saw two men walking by a swan preening on the riverbank. It suddenly rushed toward them, as if saying, “hey guys, it’s me,” but they were deep in conversation, and passed it by. It turned and waddled after them for a while. It was sad to see this beautiful and awkward swan trying to catch up, though it never will [Pauses]. It takes a lot of words to say what’s right there in a picture.

Dunn Marsh: In 2007, Sylvia was working on a contract and said she could use some help. I was happy, as always, to do that as a trade. So after we finished, she said, which print do you want? And I said the one with the goose. She looked confused, so I said: It’s running, it looks lonely, it’s chasing after these guys, and that’s how I feel, I’m chasing after life right now. When she finally realized the image I was talking about, she had this big smile and she said, Michelle, that’s not a goose – that’s a swan out of water, and that’s where you are. But you are both going to find your way back to the river. So that’s become a metaphor for me, and our friendship.

Dykstra: Another story I liked from the book, which comes around to your origins as a book editor and publisher, Michelle, is the story you tell about having nightmares and trouble sleeping. One of the things your dad would do is sit with you and have you plan out your dreams. That’s such a beautiful metaphor for life, but also for what you ended up doing

Dunn Marsh: There was a time in my early childhood when I had recurring nightmares. It was always the same – they were always black and white. They weren’t photographic, they were like drawings, and they were so upsetting that I was afraid to go to sleep. Eventually, my dad sat with me each night and said, OK, let’s plan what you’re going to dream about tonight. The act of forming a narrative, I think, eventually released those nightmares. But honestly, the fact that that I can live with so much black-and-white photography now, and that has never been a trigger for the imagery that was once quite terrifying – well, it’s a good thing those nightmares didn’t get in the way. It could’ve altered my entire trajectory!