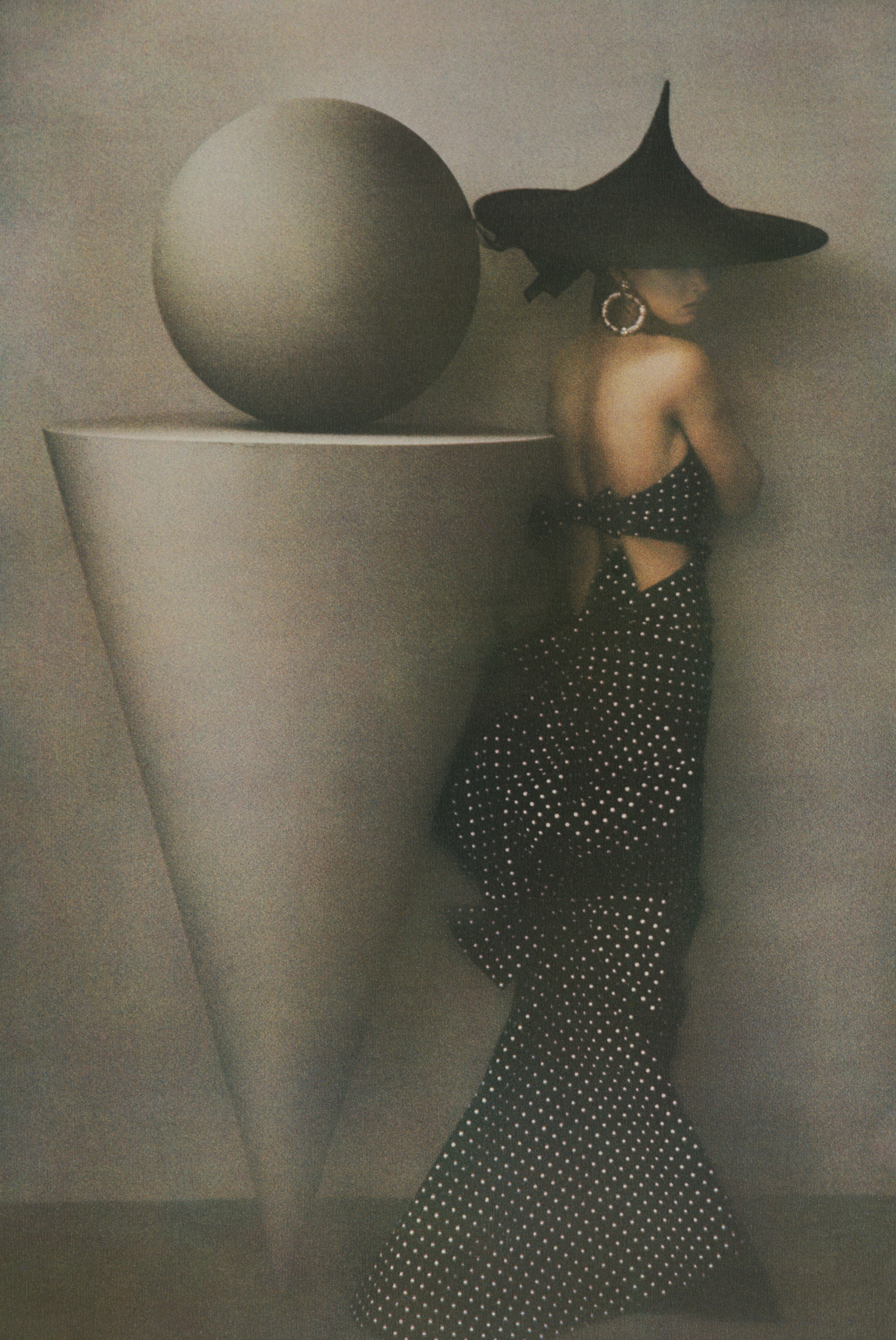

Uta Barth spent a full year photographing one relatively nondescript corner of architect Richard Meier’s Getty Center. The Getty had commissioned her to make work celebrating the 25th anniversary of its hilltop Southern California complex, and she had opted for rigor and repetition: twice a month between 2019 and 2020, she set up cameras outside the entrance to the Harold M. Williams auditorium. Every five minutes, all day long – the series is titled from dawn to dusk – she recorded the same view: a glass side door, situated to the left of a corridor. The view is vaguely familiar to anyone who has visited the museum complex, but instead of capturing its ambitious vistas, the photographs bore into the glaring whiteness of Meier’s travertine surfaces. Some images zoom even further in, past the door, so that just four squares of travertine fill the entire frame (as critic William Poundstone suggested, the square shapes and sizes of Barth’s finished images appear to mimic the tiles that comprise the Getty’s exterior). As the light changes over the course of the day, shadows and glows define these shifts. A few bright red images conjure an afterimage, or what you would see upon closing your eyes after gazing too long at the sun-bathed tiles. But the scene itself rarely changes. The door stays closed, and the corridor uninhabited, though in a couple of photographs, a long orange extension cord hints at human activity.

The Getty Center, replete with its lux Italian travertine, was both lauded and contested when it was first built in 1997 (neighbors worried about blocked views, increased traffic, and the possibility that Meier’s penchant for reflective surfaces would blind them). Yet it is hard now, after traversing freeways and taking a meandering tram ride up the hill to get there, to pay attention to the exact particulars of the museum’s strange architecture, which privileges the exterior over the interior (the galleries can feel modest, and sometimes even a bit claustrophobic). With from dawn to dusk, Barth does what she has long done. She looks closely for us, pulling us back into the nuances of an experience that we’ve likely just bypassed.

On view through February 19, Uta Barth: Peripheral Vision, a career-spanning survey curated by Arpad Kovacs, assistant curator of photographs, begins with these photographs made at, and for, the museum. It then sprawls backward, through photographs Barth has made since the mid-1990s, when her approach first crystallized into what it is now: an exacting exploration of perception, closely attuned to the way light affects how and what we see, mostly absent of human figures but never abstract. Her aesthetic is unmistakable, quiet and controlled, and surprisingly seductive. But her images do not necessarily offer immediate gratification, especially given their lack of a discernible subject. They seem instead to be chipping away slowly, across decades, at the same set of questions. These questions, which are as wide as Barth’s work is precise, all circle around what it feels like to see and perceive our surroundings.

Barth was born in Berlin in 1958. Her family moved to the United States when she was 12, after her father, a German scientist, took a research position at Stanford University. She studied art as an undergraduate student at the University of California, Davis, and in her senior year, she met photographer Lewis Baltz, a visiting professor there. Baltz had been included in the era-defining 1975 exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape at the George Eastman House, and his dry, inquisitive approach to the built environment resonates with the approach later adopted by Barth. But something else stuck with her, too: the elder photographer’s voracious interest in all contemporary art, well beyond photography. At a time when photography’s place in the fine arts remained new and precarious, he did not treat it like a siloed medium. And indeed, the work Barth began making before graduating from UC Davis in 1982 and then continued making after enrolling in the MFA program at UCLA (she graduated in 1985) experiments with the medium’s boundaries.

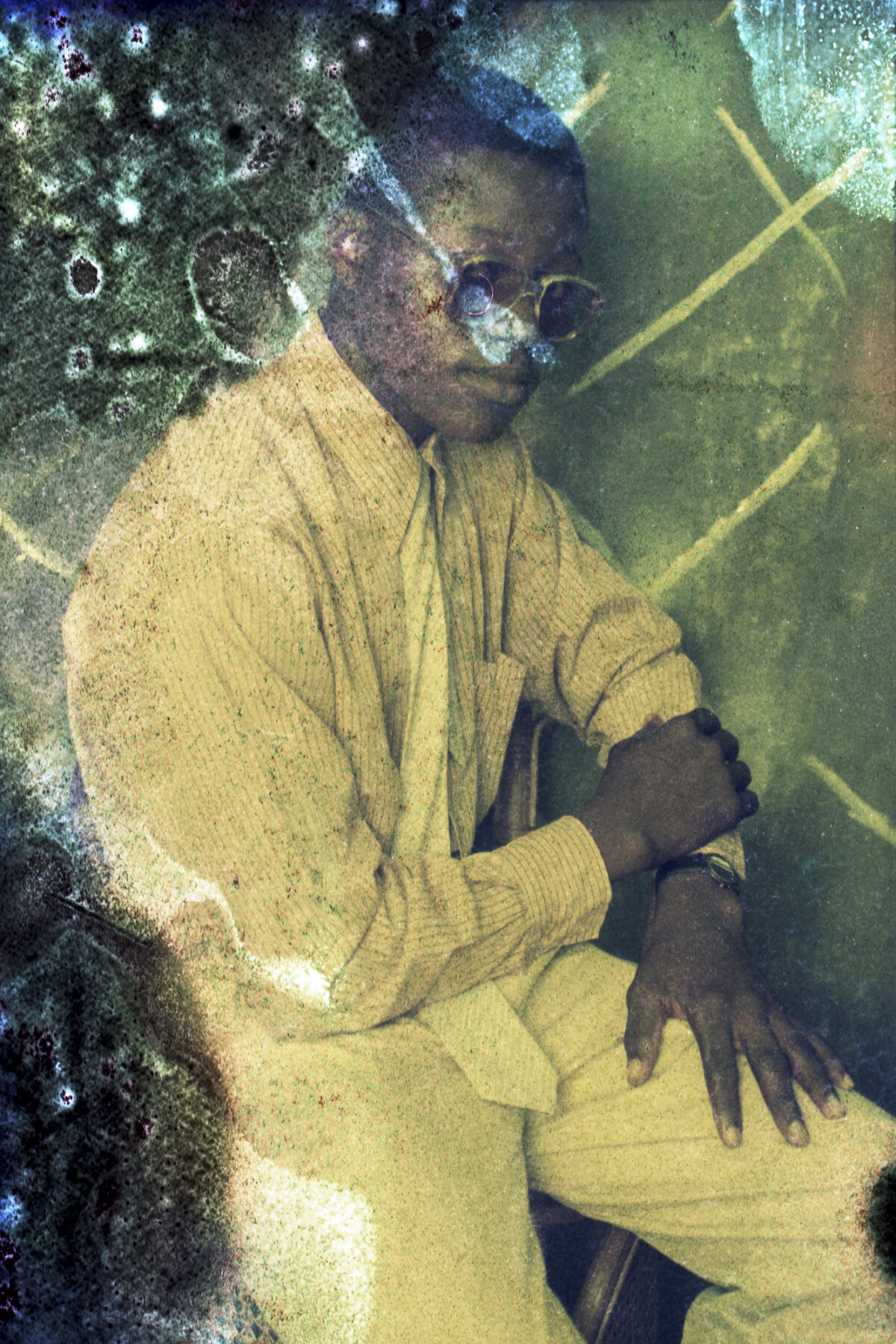

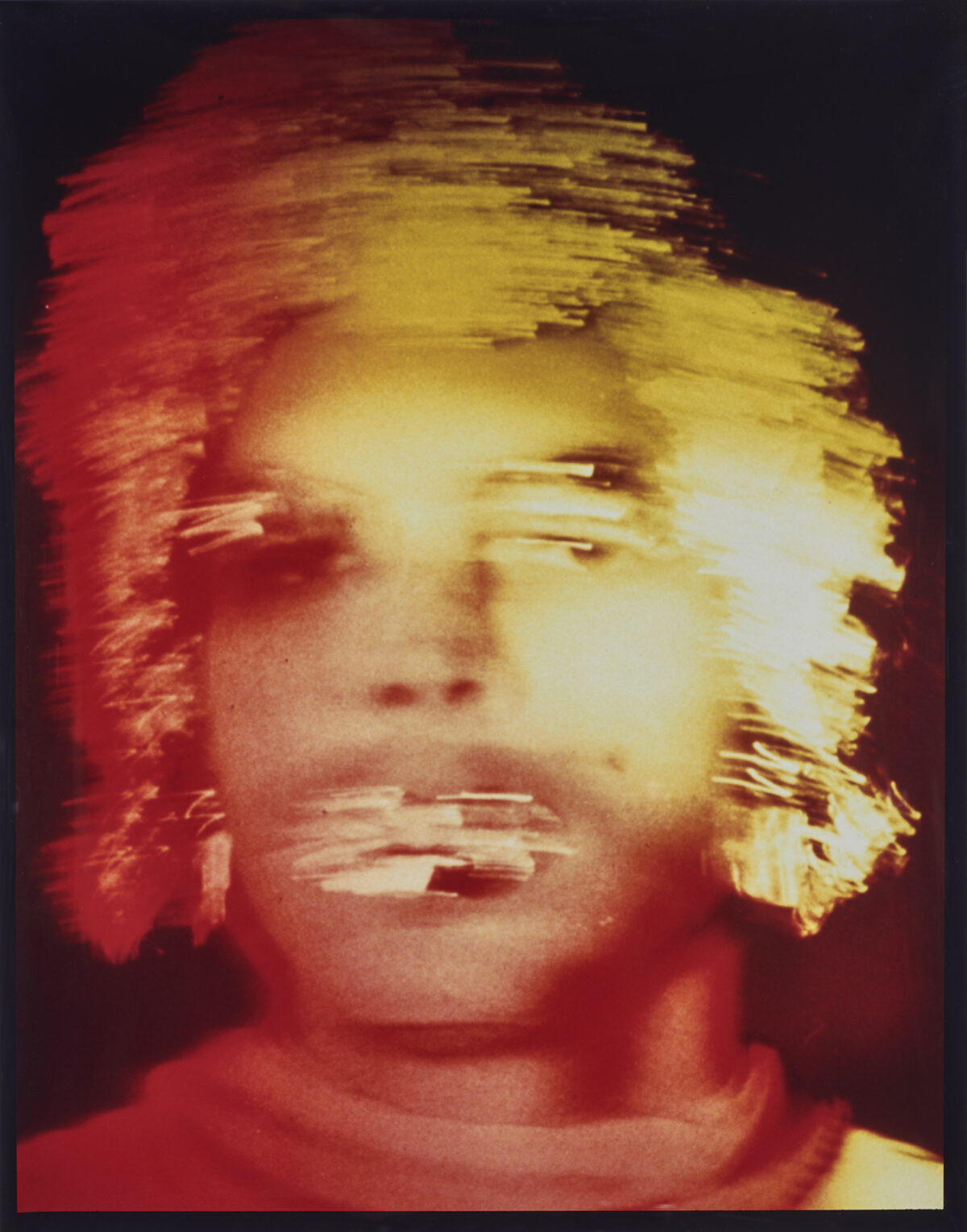

A selection of Barth’s early work hangs in a side gallery tucked behind the bookshop, far enough from the main galleries to feel like a prelude rather than a first act. So often, an artist’s early work does not reflect her later output – consider the harrowing, expressive portraits Eva Hesse made in her early 20s, leaps away from the sculptural experiments that would define her. But Barth’s early photographs, made between 1979 and 1990, are remarkably aligned with her later interests and with shifts in conceptual photography generally. In one series made while she was still an undergraduate, One Day (1979-82), two bare feet appear near the top of the frame, right in front of a window, with floor-length curtains pulled to the side. Across the eleven images, the light from the window changes, brightening and spreading further and wider across the floor. The series recalls the way artists like Richard Long or Bas Jan Ader used photography: to document minute moments across durational performances. But in Barth’s images, it is the light and not the figure that moves. In another series, Every Day (also 1979-82), Barth repeatedly photographs a segment of a sparse room with a painted wood floor and a white wall. Sometimes, the image includes a metal folding chair with a coat draped over it (the chair also appears without the coat); a black utility cord coiled on the floor; or a cardboard box filled with garments. Barth has bordered the scene with black tape which, in the photograph, appears so perfectly square that you assume it must have been superimposed, added after the image was printed. But in fact, it is in the photograph; in taping off the floor and wall, Barth calculated and compensated for the perspective shift the camera would document, resulting in an apparent flatness that plays with the mind’s expectations.

Barth’s interest in perception has evolved since then, away from such tricks toward subtler, prolonged perceptual experiments. In interviews, she often speaks about reading Lawrence Weschler’s book about Robert Irwin, Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, the summer before she started graduate school. The book traces Irwin’s lifelong pursuit of presence, and how he shifted from trying to capture light and translucence in sculptural works to using light itself as his medium. “That’s conceptually a huge step, to take a room and bathe it in yellow light and decide that’s an artwork,” Barth recently told the Los Angeles Times. Irwin is associated with the California minimalist movement Light and Space, which Barth has cited as an influence – and though she has frequently voiced her frustration with Los Angeles itself (she called it “the most alienating city I have ever been to,” in Bomb magazine, before conceding, “I cannot picture myself making work somewhere else”), her work relies on what she calls the city’s “visceral and blinding” light.

In …and of time (2011), one of multiple series made in and around her own home, Barth photographed the light from her living room window as it hit the wall above her burnt-orange sofa. At certain times of day, the light casts such sharp shadows that you can see the windowpanes and hints of the foliage outside; at others, an indistinct soft light bathes the wall. The couch itself is usually barely visible, just a thin line of orange at the bottom of the frame, enough to ground us in a real room but not enough to fool us into reading this as an image of a domestic interior. The images from …and of time hang at staggered intervals (two close together, one on its own, two more close together), a strategy the artist has long used to suggest to viewers that the photographs together constitute an installation, and thus an experience – that they are not just pictures on a wall to be viewed sequentially.

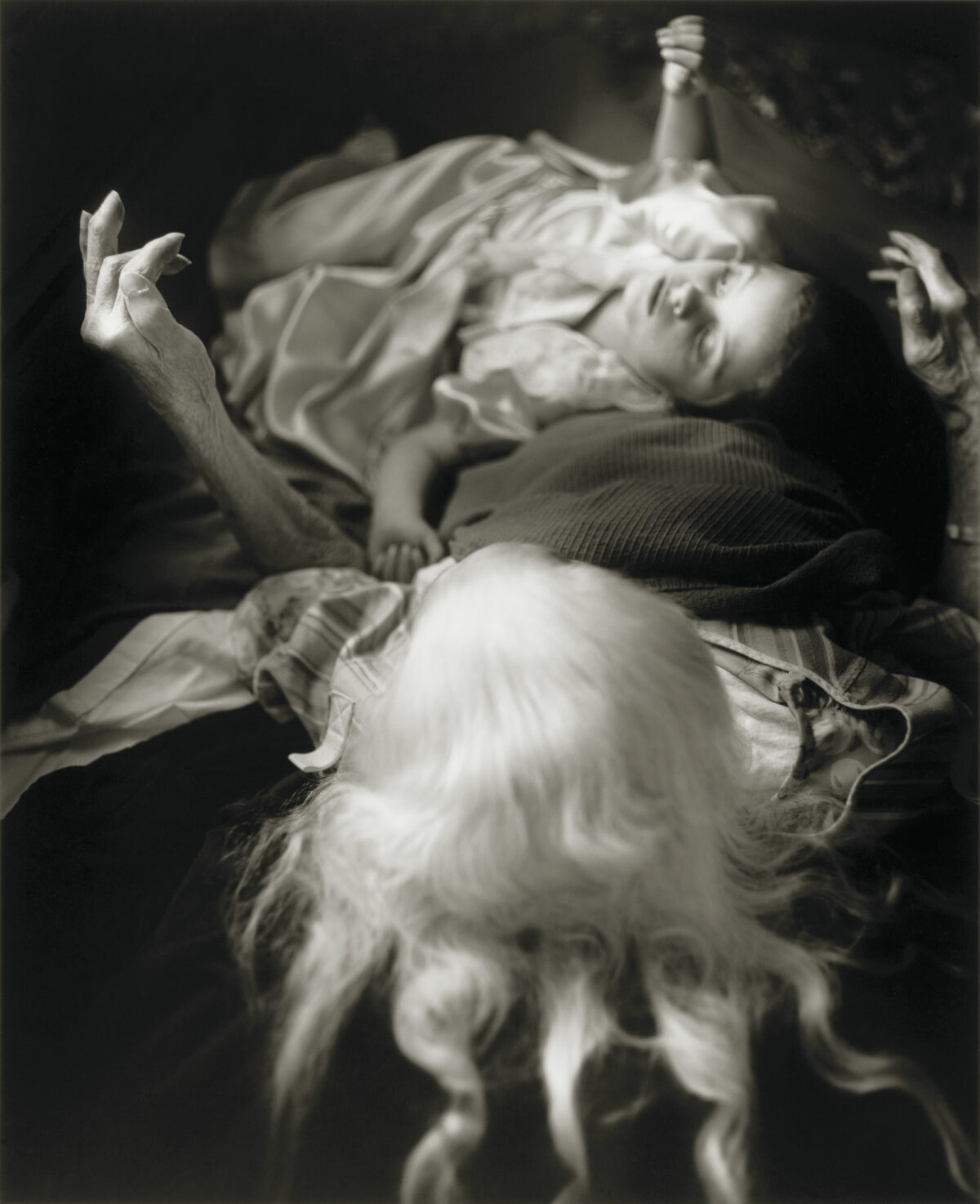

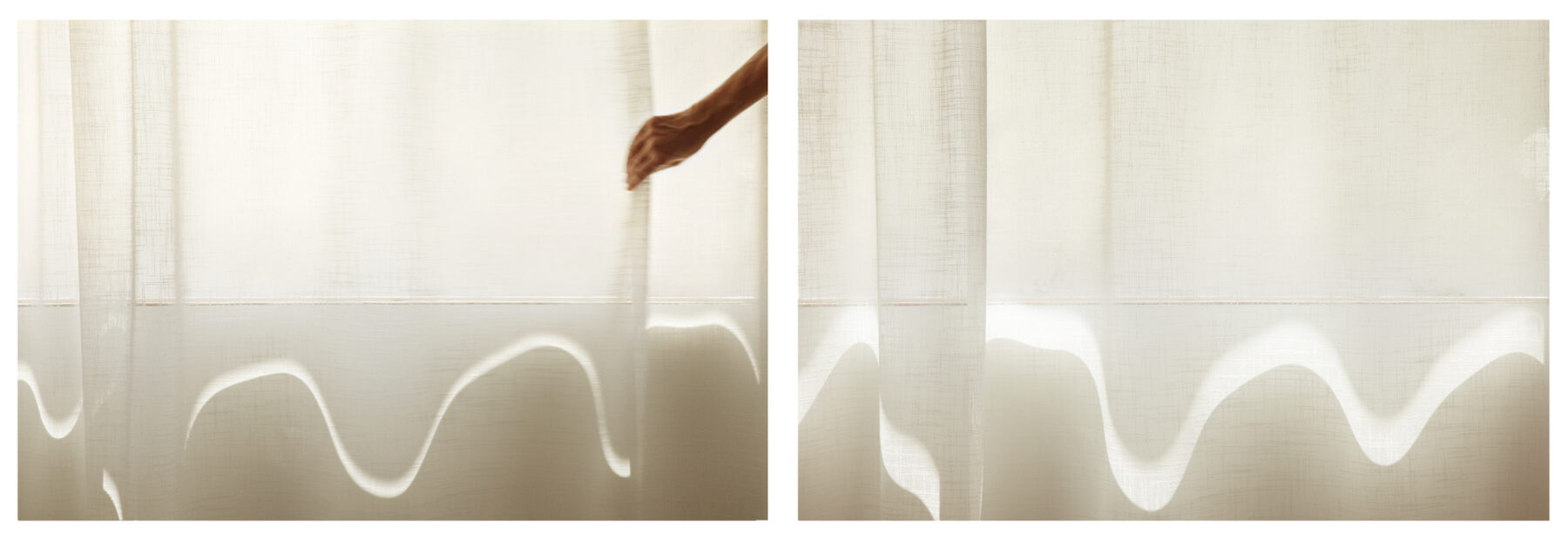

While the majority of her images made between 1990 and 2010 maintained a naturalistic relationship to light, photographing what the eye could perceive, Barth experimented with manipulation for …and to draw a bright line with light (2011). She pulled at her sheer white bedroom curtains to create sharp bands of white light that, without her intervention, would not have quite so distinctly resembled lines. In an effort to be transparent about her own involvement, she included her own hand and forearm – a rare glimpse of the artist’s body. Again, these images trace the passage of time, as the band changes in width and length as the day progresses.

Time shows itself differently in Untitled (2017-2018), a series of images of the exterior of Barth’s studio. Each photograph includes a view of the thin line of windows at the top of the frame, and a hint of gravel on the ground or the surrounding foliage, but the white plaster wall takes up the bulk of the space. Its surface’s whiteness is uneven, stained by moisture retention in the dry Southern California climate. The wall label compares this expanse of whiteness to Robert Ryman’s abstract monochromes, though I think of Mary Corse, who also works in Southern California, and the white gridded paintings she has been making since the late 1960s by incorporating microscopic spheres of glass into acrylic so that the surface intermittently refracts and glows. Corse, like Barth, found in this way of working an interest that has held her attention for decades, because every variation in light, the way it changes as the viewer moves, gives different insights into the experience of being in the world. What Barth’s work – chronicled in Peripheral Visions – proffers, with its consistency, its sensuality, and its methodical close looking, is a focused way of grappling with vastness.