In 2002, the Museum of Modern Art closed its doors for two years to make way for its Yoshio Taniguchi renovation. In the interim, it opened MoMA Queens, a warehouse in Long Island City that housed temporary exhibitions as well as its entire permanent collection. At the time, I was enthusiastic about this facility and optimistically envisioned myself going there one day to peruse the stacks, rifling through Picassos and Pollocks and maybe uncovering a long-lost Joseph Cornell or Louise Bourgeois. I am a flea-market hunter at heart, and nothing would make me happier than to see the history of art de-installed and presented without the hoopla of the white cube, so that I can choose for myself the treasures from the tchotchkes.

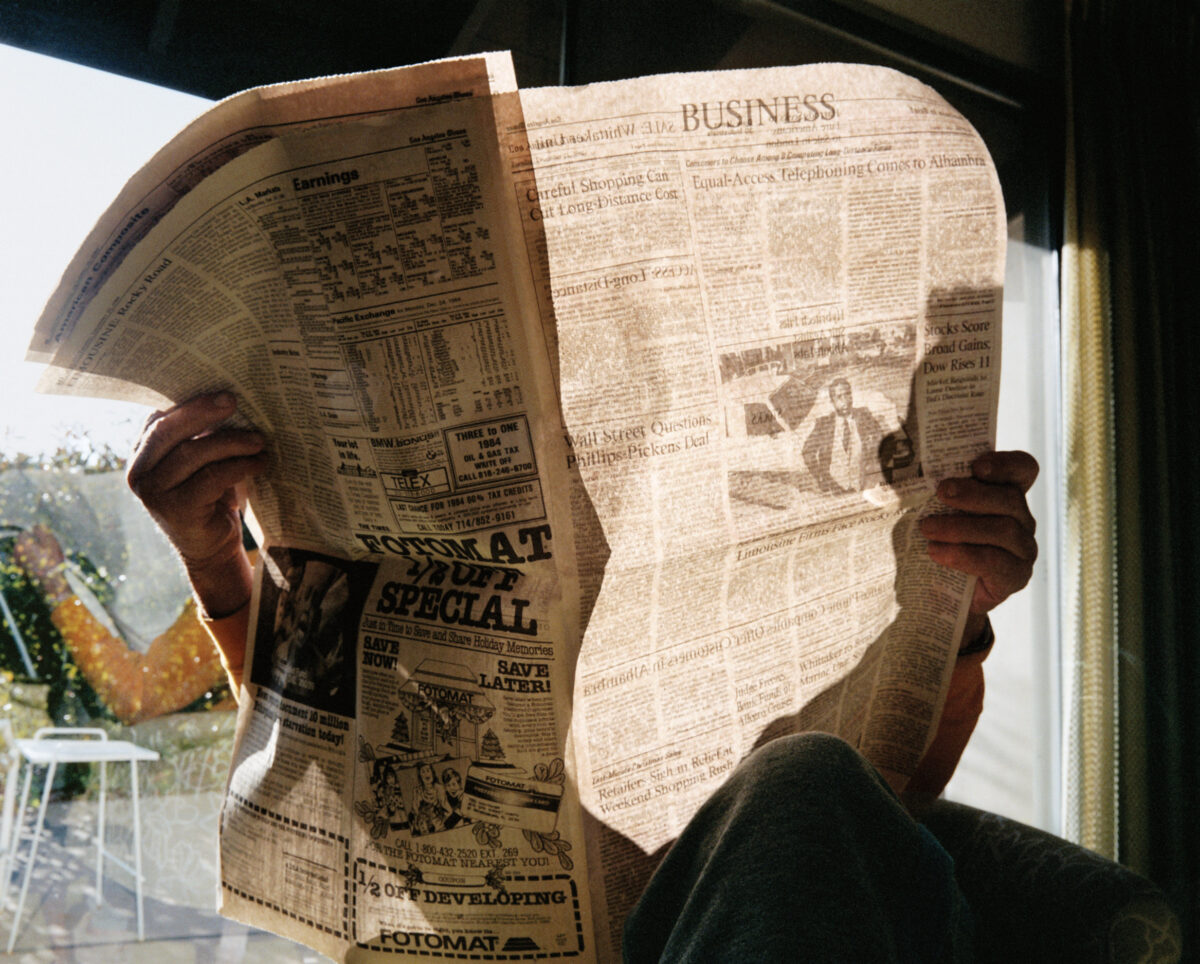

Although I never did rifle through the stacks at MoMA Queens, no artist brings me closer to that fantasy than Louise Lawler, who for four decades has taken her camera behind the scenes of the art world. Foraging in collectors’ homes, auction-house racks, museum storerooms, and art-fair booths, Lawler has created a body of work that could easily be mistaken for mere documentation of the economic structures of the art world. In Lawler’s oeuvre, art is obscured by crates, overshadowed by wall labels, displayed beside refrigerators and television sets, and crammed into corporate offices. Art is sometimes even found on white walls in galleries but, Lawler’s photographs suggest, that is only a temporary resting place in its journey through the global marketplace.

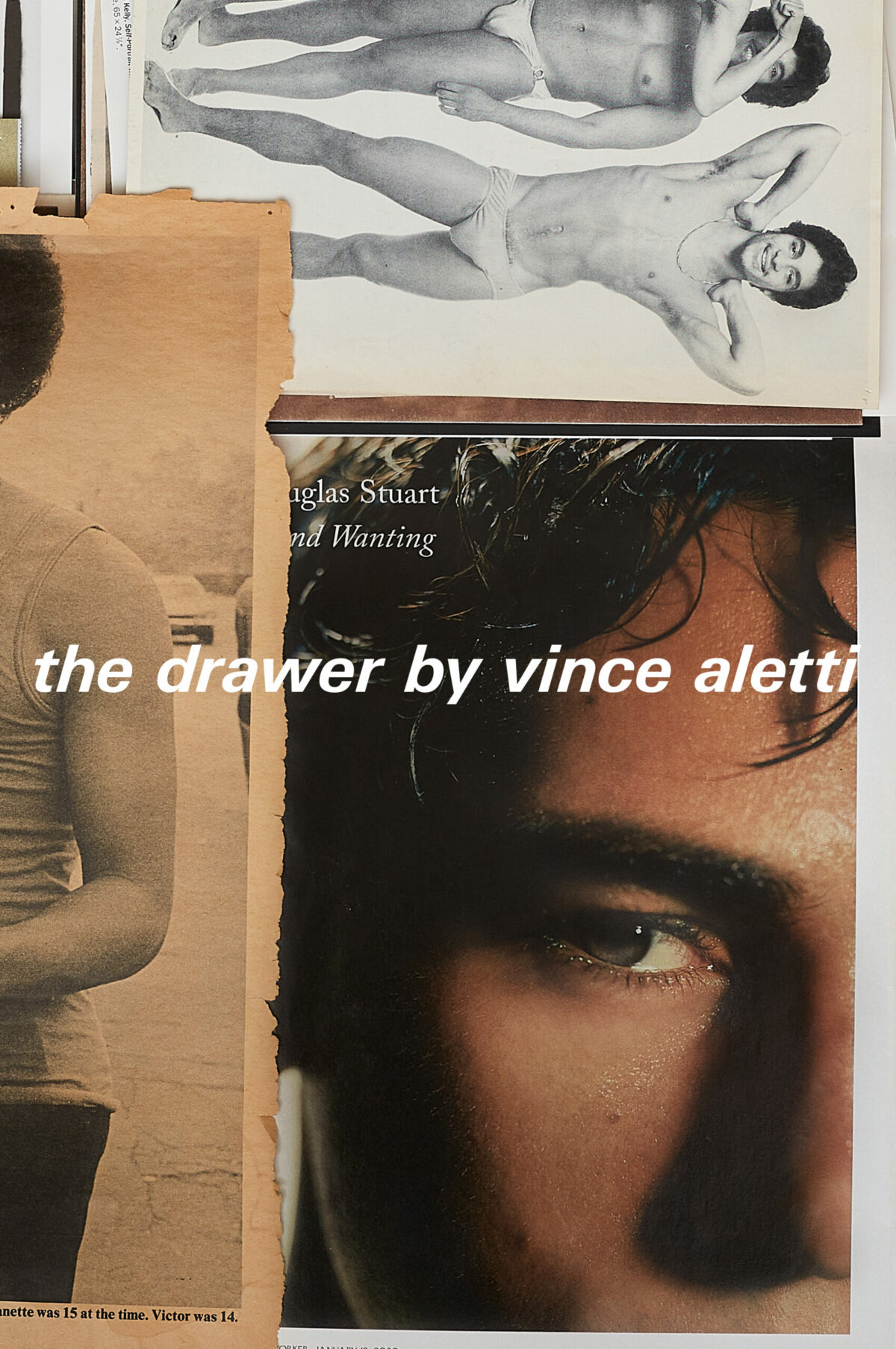

While documentation may be one valid interpretation of Lawler’s ongoing project, it fails to take into account the many conceptual strategies that she has employed over the years. In Lawler’s retrospective Why Pictures Now?, on view at MoMA through July 30, curator Roxana Marcoci and curatorial assistant Kelly Sidley underscore this conceptual bent, reclaiming the artist’s legacy as a member of the Pictures Generation, as a feminist, and as a pioneer in the field of institutional critique. In Marcoci’s view, Lawler is not carelessly capturing the underside of the art world; she is “sabotaging the idea of artistic expertise.” In other words, she is strategically appropriating key works by primarily male artists within her framed interiors and then re-appropriating her own works in a variety of formats, from paperweights to wallpaper.

Born in 1947, Lawler has been situated in the art world since the late 1970s, when she worked for a time at the Leo Castelli Gallery. A witness to the rise of celebrity culture and the influence of the art market on contemporary art, she created works that commented on these phenomena from the beginning. In 1972, in reaction to an all-male show set on the piers along the Hudson and organized by curator and conceptual artist Willoughby Sharp, for whom she was an assistant, Lawler recorded Bird Calls, a humorous sound piece in which she trilled out the names of the male artists in the show – Vito Acconci, John Baldessari, Gerhard Richter, and others – as if they were the songs of birds. Ten years later, in her gallery debut at Metro Pictures, she displayed Arrangements of Pictures (1982), hanging the work of other gallery artists as her own installation, presented for sale as a single work by Lawler. (It found no takers.) Already, early on in her career, she was employing feminist strategies to deflate the myth of mastery conferred on her male counterparts and using appropriation not as an end in itself, but as a means to deconstruct the mechanics of displaying and selling art.

By then, she had created the photograph Why Pictures Now (1981), for which the show is titled. In this image, a matchbook stands in an ashtray with the titled words on its cover, posing a question to viewers that they must answer for themselves. It is a double-edged query, not only asking why viewers look at photographs, but why the artist is making them. This was considered a cutting-edge line of inquiry in the early 1980s, when a media-driven generation picked up the camera in order to interrogate the public’s reliance on photographic information. It is all the more relevant today, when photographs are routinely re-circulated on social media to perpetrate fictions as much as facts. In 1990, Lawler used an image of the actress Meryl Streep in lieu of a self-portrait, with the words, “Recognition Maybe, May Not Be Useful,” running across the picture. This work slyly deflates the importance of celebrity and name recognition, two qualities valued as much in the art world as they are in Hollywood. This is even more keenly true in the Trump era, and this image has been used on a poster for MoMA’s exhibition.

Lawler is also well aware of the market distribution of photographs themselves, the way editions are created to limit the multiplication of single images so that they may retain market value. While maintaining editions for her prints (editions of five, though it can vary), she has also replicated and reformatted her images in a variety of media, extending their applications in a wide range of venues. For example, there are her “tracings,” large-scale black-and-white drawings based on her photographs, created in collaboration with illustrator Jon Buller. These works, which look like sophisticated pictures from a coloring book, drain the originals of their sensitive coloration, yet invite viewers to fill in the blanks from memory – they are not necessarily shown with the photographs on which they are based. Lawler has also created works that she labels “adjusted-to-fit,” meaning that the photographic image is stretched or compressed to match each particular exhibition space, then generally printed on vinyl and affixed to the walls as wallpaper. The skewed perspective of these resulting works requires viewers to adjust their vision to correct what they see for what they presume to be reality. This only heightens the voyeuristic undercurrent in the original photographs, making viewers work twice as hard and feel doubly conscious of the act of looking.

Rarely are these strategies performed merely as aesthetic experiments; they are more often attached to subtle political critiques. This is most keenly seen in her two “adjusted-to-fit” renditions of Civilian (2010), and No Drones (2010/2011), based on photographs of Gerhard Richter’s paintings, Schadel (Skull) (1983), and Mustang-Staffel (Mustang Squadron), (1964), as they were being installed in the Albertinum museum in Dresden. Her photographs are shot at an angle that reveals the hanging devices behind the paintings, and the skewed view is exaggerated when stretched into wallpaper, creating an almost anamorphic dimensionality. By labeling an image of a skull with the title Civilian (2010), and by underscoring that Richter’s WWII squadron operated with “no drones,” Lawler brings these pictures into the realm of contemporary warfare, critiquing the fact that drones, often used as aerial cameras, are inventions of the military.

Still, I keep returning to some of my favorite pictures by Lawler and relishing how they allow me to peer into a world that often treats me as an outsider. With Big (2002/2003/2016), I am taken inside Marian Goodman’s booth at the 2002 Art Basel Miami Beach fair to see a mammoth photograph by Thomas Struth hanging over the disembodied head of Picasso by Maurizio Cattelan. The Struth photo shows visitors at a museum gazing in awe at artworks out of view while the Cattelan cuts a modern master down to size. In Big, Lawler juxtaposes two opposing views of art appreciation in a single frame: one that treats fine art as a near religious experience, the other seeing imitation (even with irony) as the highest form of flattery. Together, they encompass a fair range of contemporary art, captured by Lawler in a single frame.

Big exemplifies Lawler’s talents, which are intriguing and complex, while packing the sarcasm of a New Yorker cartoon. That sense of play should never detract from an appreciation for the seriousness of her intentions. But sober consideration of her accomplishments should never diminish the wit and humor in evident display. The answer to the question: Why pictures now? is clearly evident in Lawler’s works, which invite us to see photographs – not only what’s in the pictures but the pictures themselves – from a more critical point of view.