Cuban-born María Magdalena Campos-Pons is the visual arts’ most recent recipient of the so-called genius award of the MacArthur Foundation. It acknowledges the creative activity in a wide range of media by this remarkable artist. That diversity, nourished by symbolic and performative roots in the African diaspora religion of the Yoruba people, is on display in an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum in the Sackler Center for Feminist Art (through January 14, 2024). Campos-Pons calls herself “a photographer impersonator,” but as the exhibition makes clear, photography lies at the very heart of her work.

Lyle Rexer: The exhibition is physically situated in the Center for Feminist Art in the Brooklyn Museum around the central permanent installation of Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party. This constrains its capacity for presenting more of your installation work. I wonder if you felt frustrated by that.

María Magdalena Campos-Pons: No, not really. At first I was wondering how this would work because I usually am concerned about how pieces can be installed, but I am very pleased at how Carmen Hermo [associate curator in the Sackler Center] has installed the work. More than that, because it is organized thematically, she has created for me and for all the visitors ways of discovering new aspects of my work.

LR: One of the consequences of this limited space, I suspect, is that there is very little early work from the period before you left Cuba in 1991. There is also a lot of photography in Brooklyn. Was your early work mostly painting and drawing?

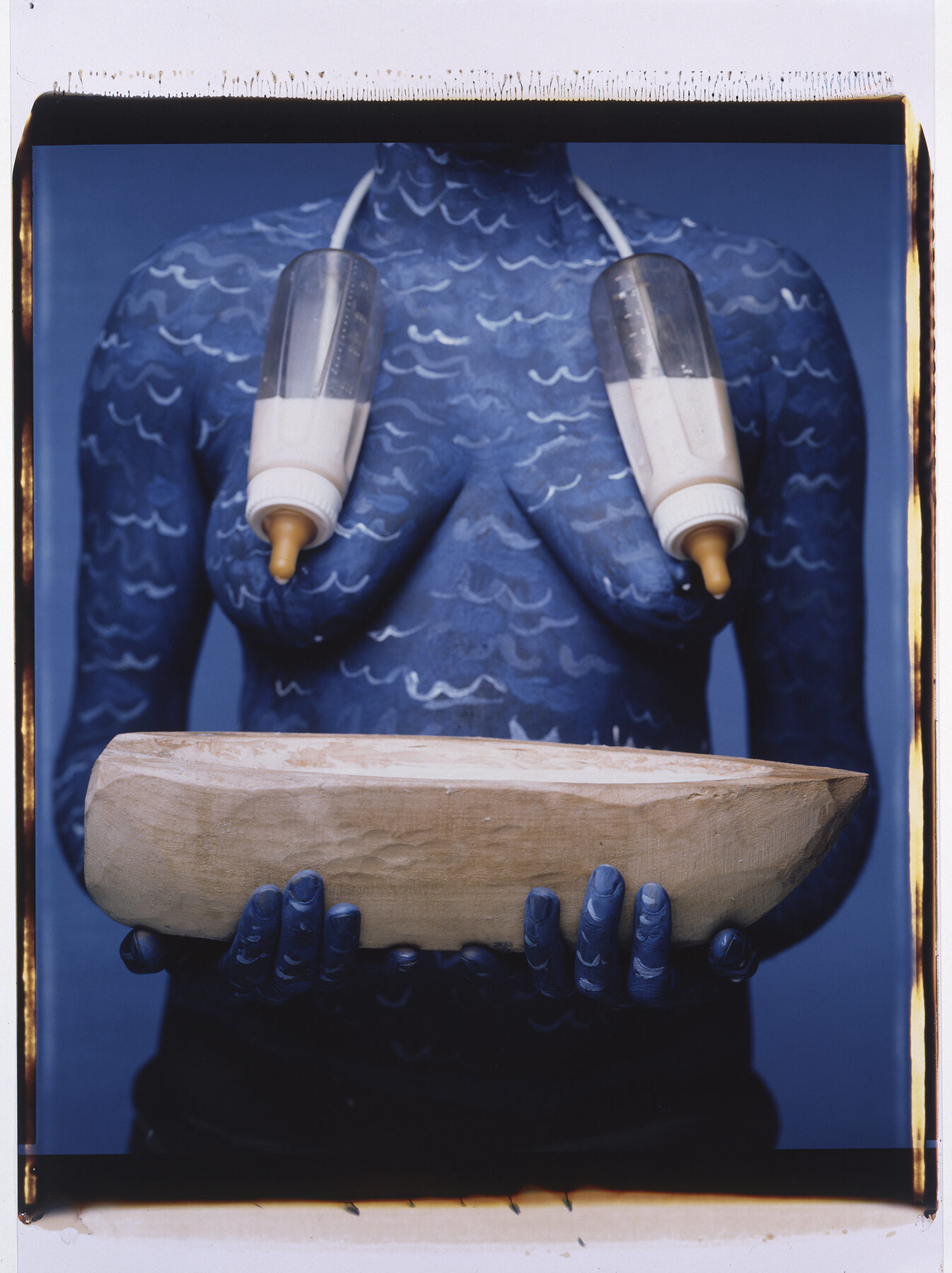

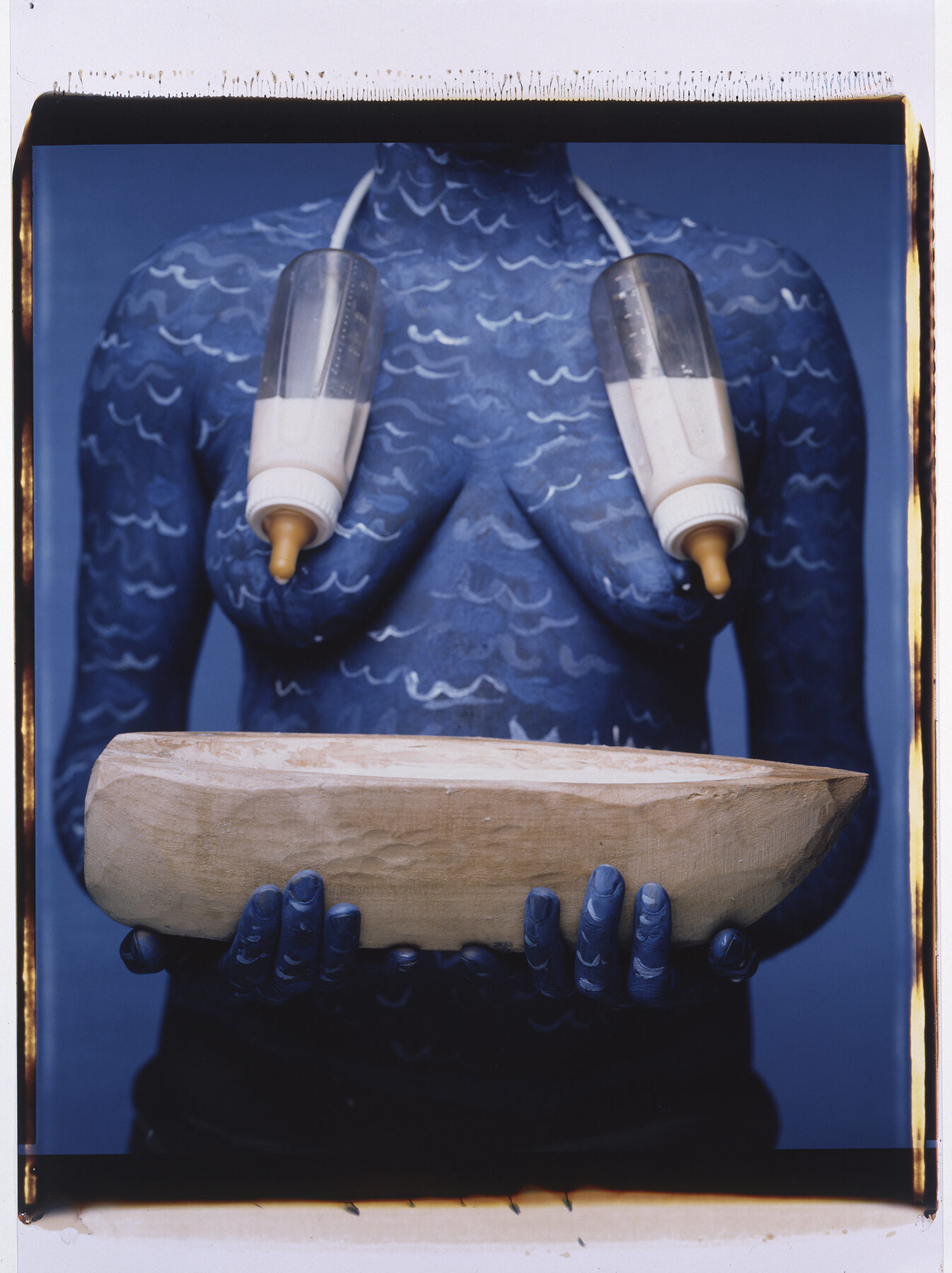

MMCP: I graduated from the Instituto Superior de Arte in 1985, and my work was – and still is – very inquisitive about the nature and relationship of materials, forms, and ideas. Perhaps the piece in the show that comes closest to the work I was doing at that time is called I Am a Fountain. I was interested in moving away from the picture plane of the rectangle and creating a conversation that could be in the form of silhouettes or discombobulated forms of assemblage. After I came to the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in 1988 as an MFA student, I created a large installation piece called Erotic Garden, now in a collection in Cuba. This explores aspects of the female body and love. It was an entire set of pieces about contraception and IUDs – things that are inserted into women’s bodies, with a T- form that copies the device and mimics the fallopian tubes. I had been fascinated since I was a child with wood carving, and this installation involved many carved pieces.

LR: So it makes sense to call your work feminist, as the curator does.

MMCP: People said that, but I didn’t know what a feminist was. I was curious and I wanted to explore these themes of the female body and also how it was represented in different cultures.

LR: A detail of a photograph opens the catalogue. It’s from a piece titled Nesting II and portrays you using your hands and eyes to imitate an owl’s eyes. Several things strike me about this: first, the importance of your hands in the exhibition – there is so much handwork, and body work, from painting and sculpture to performance. Second, and this relates to photography, the importance of the eyes and seeing. How did photography work its way into your art and what is its significance?

MMCP: My work is all connected. I was a cinephile in Cuba. I could watch the same movie many times. I still do that. I was a member of the cinematheque in Havana, and the conversation around those films was very rich. That was my real inspiration. I consider myself a photographer impersonator. I am not someone who spends all her time in the darkroom with the alchemy of paper and materials. The tools and the form of photography I have been using are very performative. They have allowed me to have an immediate connection with composing a structure for the body in performance. When I was a student at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, I studied in the integrated media program, which includes photography, video, and performance. This was very important to me. I was also introduced to a particular camera, as well, the 20 x 24 Polaroid camera. The school had one at the time.

LR: That was important as a staging device, I can see. It is also a very physical tool, producing substantial objects.

MMCP: Yes, and I was interested in the materiality of photography and how that connected with other media. I made an unorthodox form of a photograph by transferring a sepia-toned image to a canvas primed with monochromatic acrylic. I used a hot iron to make the transfer, and what I got was this beautiful result. I was so proud of myself for being so clever! To make a photograph like a painting was always considered a crime by photographers. But that line between mediums has always been the place for me. For the piece Umbilical Cord, I needed to open holes in the prints so I could run a wire linking the images to make a statement about the connections in families across time. A photographer would never have done that.

LR: By that time, the late 1990s, many artists were experimenting with the forms and materials of photography, moving an image from one medium to another, breaking it down, opening it up.

MMCP: Everyone who came to my studio was very open and enthusiastic about the work, all my assistants, people who worked with me at the Polaroid studio in Manhattan. I had not been looking for people who were breaking things open, but of course I knew of artists who were using photographs brilliantly – Rauschenberg, Warhol, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, but I was thinking in a different way from all of them.

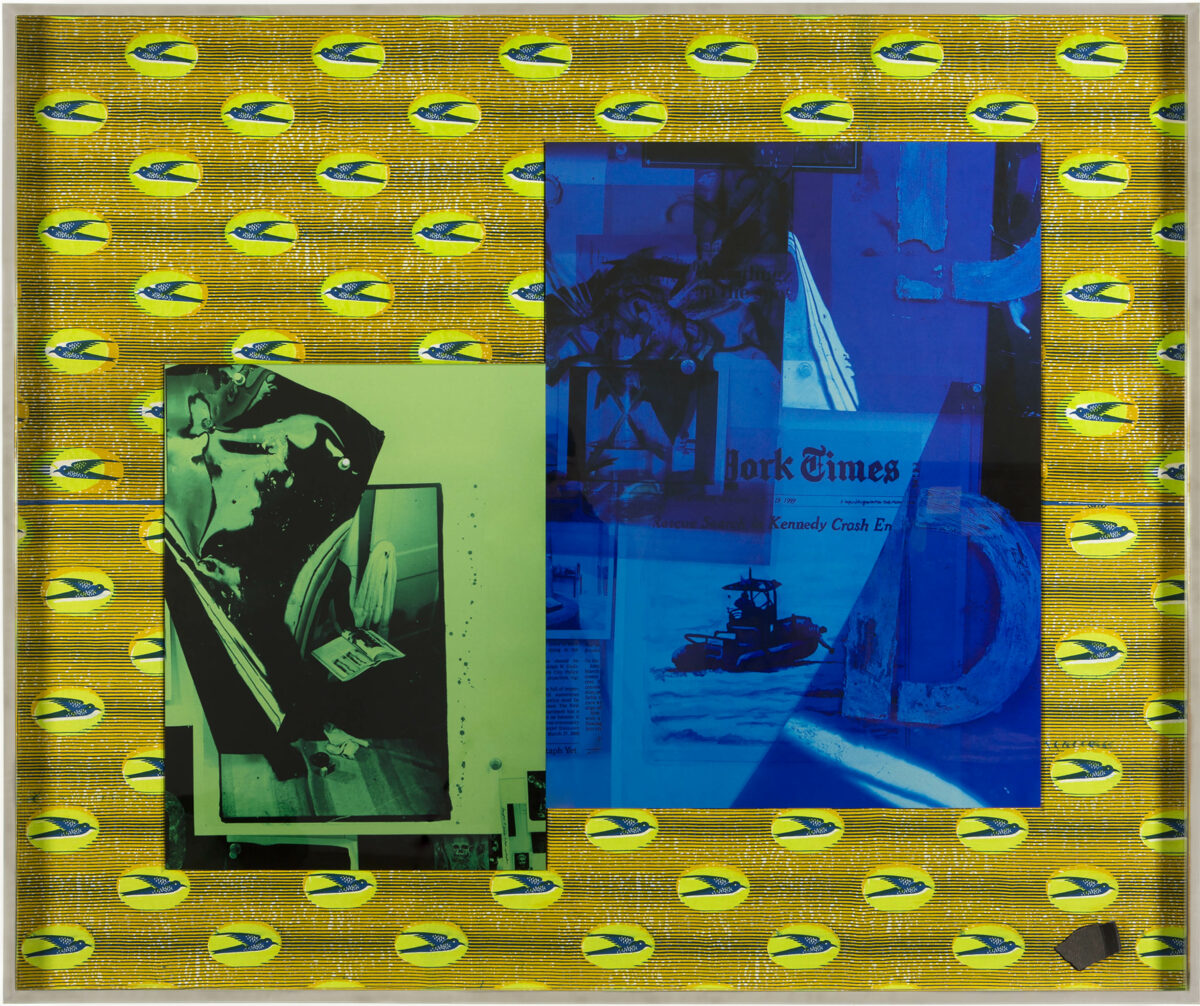

LR: You mention Rauschenberg, and I was very much taken with the work you did during a residency at the Rauschenberg studio on Captiva Island in Florida in 2016, the Extreme Weather series. It is a lovely location when the hurricanes aren’t blowing.

MMCP: I was so inspired there! He was in my mind all the time, and I was stealing anything I could from what he did. I was walking his ground, breathing his air. And I worked like crazy. He had left a lot of fragments lying around, I suppose from work he never got to do, and I borrowed a piece of a car door to make a transfer for something I was working on. Again, I would never claim the territory of a photographer, but I use photography all the time. I have taken thousands of photographs – not Polaroids – all over the world, and I never know how I might use them. When I was in Africa, I was working in an abandoned factory where I had set up a studio, and I became fascinated by the spiderwebs there, and how they would seem to change as the light changed during the day. There were piles of dusty boxes that I considered beautiful, and I made hundreds of photographs. I don’t have the eye to be a documentary photographer. I am whimsical, and I use photographs to build things that are spiritual to some extent, that convey specific ideas. Maybe it’s my own lack of respect for the rules that has allowed the work to be successful or revelatory.

LR: You hunt and gather. You never know what will be useful. It’s like keeping a visual diary of possible inspirations.

MMCP: When I arrived in Nashville to teach at Vanderbilt, I was overwhelmed by the magnolias.

LR: They’re the obvious inspiration for the stunning triptych of painting and photography, Secrets of the Magnolia Tree (2021).

MMCP: It’s possible I have more than 10,000 photographs of magnolias! I have taken them from every angle. I take them every time I walk in the garden. It has also transformed what I do with photographs. During the pandemic I was locked down here and I started intensively wandering around, and that led to this project.

LR: Finally, there are two important words that occur in titles of works that I would ask you to respond to. The words are calling and path. I think of calling as your recognition of your role as an artist and path as a demonstration of a way to achieve it.

MMCP: [Laughs] The works I made around these words respond to the very particular way I structure my approach to taking a photograph. The Calling (2008) refers to a dream I had about being called to serve in the Yoruba priesthood, which is my family tradition coming from Africa. My grandmother was a Yoruba priestess. I woke up from this dream and I said, wait a minute. I am not that. I am something else, but I could do a service, like a priesthood, for the arts. So in Brookline [Massachusetts] in 2003, I set up a space for artists called GASP (Gallery Artist Studio Project), with studio space, a gallery, a space for discussion, and a garden. It was a beautiful experiment with artists as curators, and many types of people were invited in for conversation – scientists, artists, politicians, anyone. For the piece itself, I dressed myself as if I were doing a ritual of initiation, using sacred powder to allow for conversation with spirits. I painted myself white and covered my hair, which is mandatory in the Yoruba priesthood.

LR: Like the performance you did at the Guggenheim at the opening of the Carrie Mae Weems exhibition.

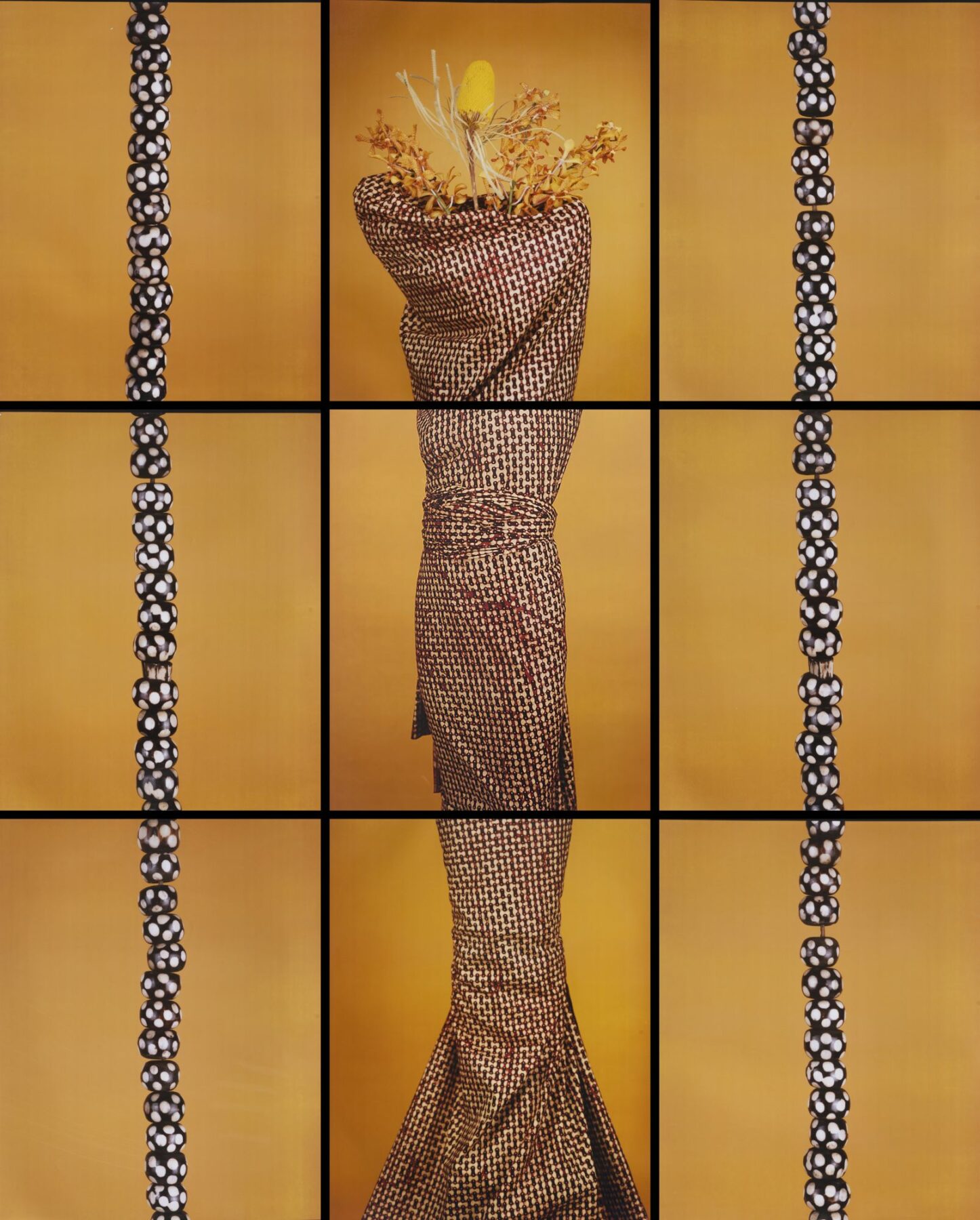

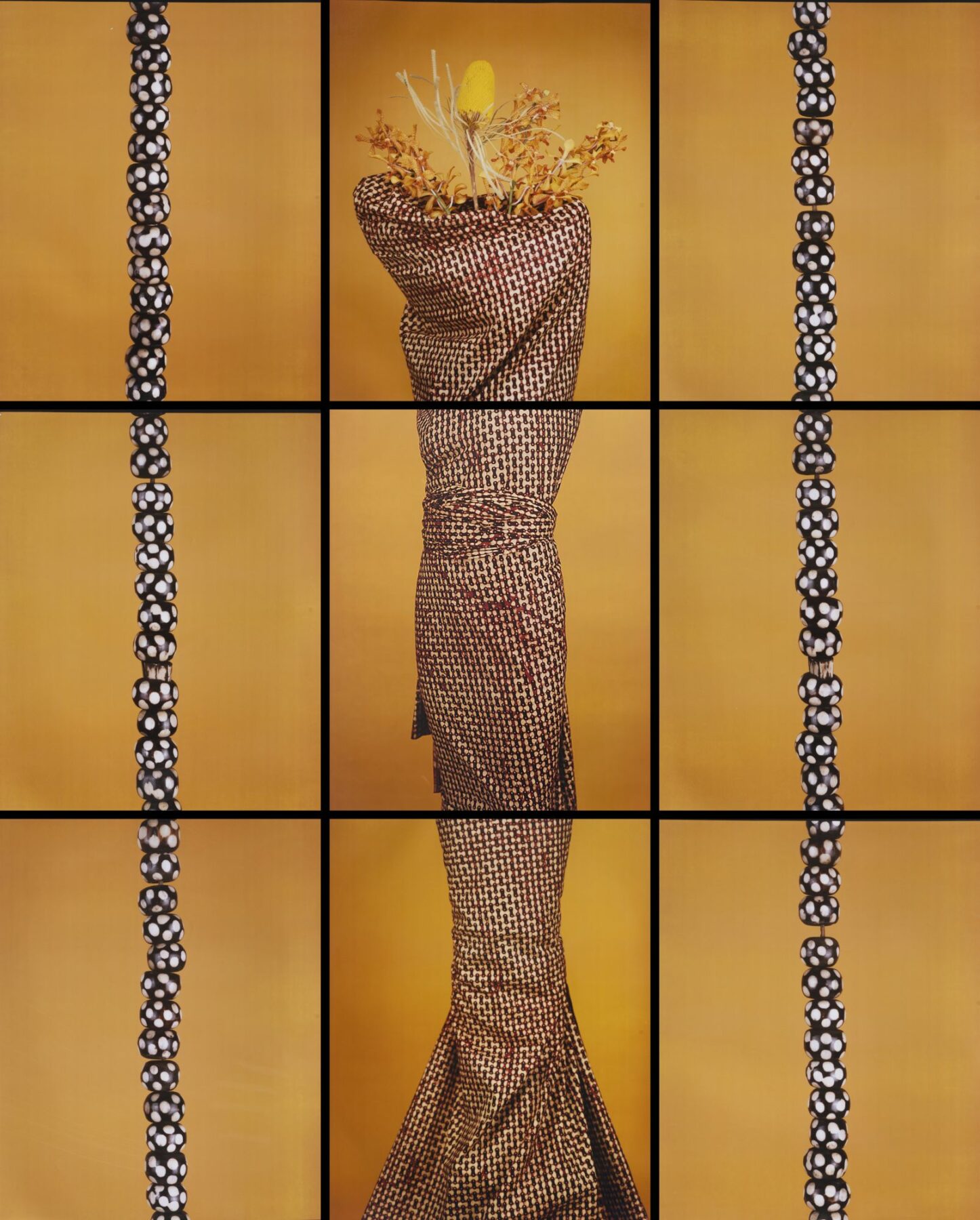

MMCP: So that is the calling. The Path (1997) is a spiritual series in which I use color codes from Yoruba traditions. Both The Path and The Calling belong to my inquiry into the extent that I could make the language of contemporary values pertinent to exploring and respecting the traditions of the Yoruba people in the diaspora. Red and white, for example, are color symbols for destiny, the colors of the deity, which opens and closes the door to the journey of life. For believers, there are things that you do and don’t do, but I attend to both in my work. The religion says avoid entanglements, but I create entanglements all the time. The point is to find your path through them.