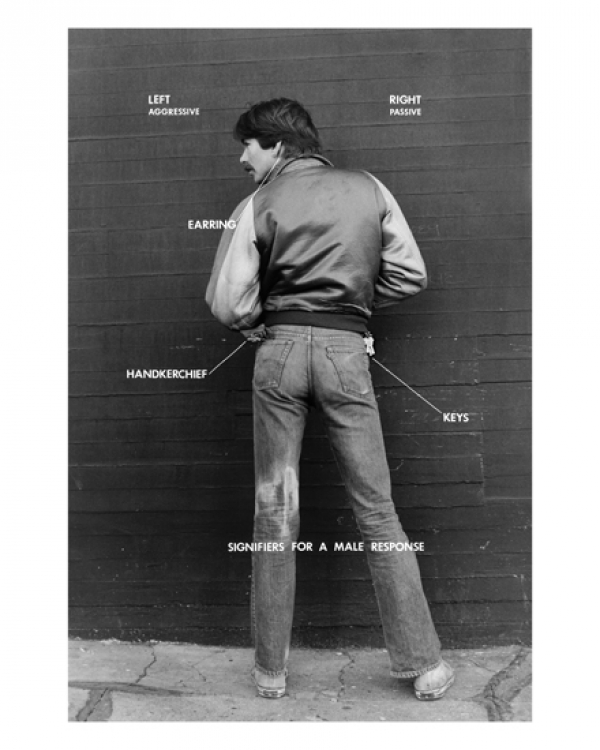

When Hal Fischer published his wry, straightforward Gay Semiotics photographs in 1977, he wrote an essay to accompany them. “Traditionally western societies have utilized signifiers for non-accessibility,” he explained, citing wedding and engagement rings. “Signs for availability simply do not exist.” But in gay culture, the reverse is true, he went on to say; such signs not only exist but are varied and nuanced.

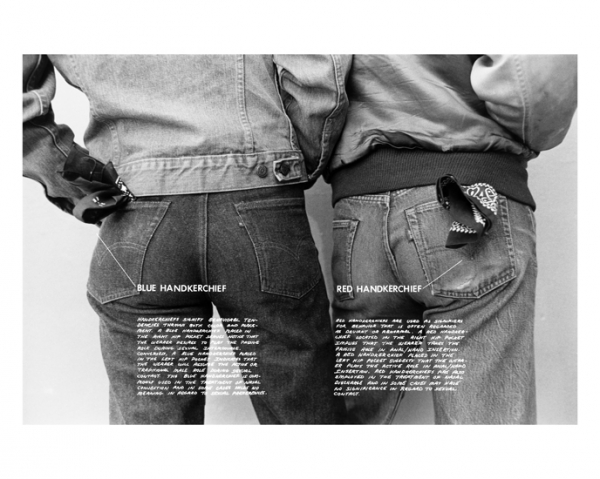

His photographs, which he referred to as “research,” lay out such signs. In one image, two men in jeans, seen from behind, stand next to each other. Each has a handkerchief in his back pocket. Given that the image is black and white, you can’t tell red from blue, except that the text superimposed onto the image tells you which color is which. A blue handkerchief “signifies that the wearer will assume the active or traditional male role during sexual intercourse.” A red one signifies “behavior often regarded as deviant.” Of course, there’s also the possibility that a red handkerchief, or a blue one, could be used for “treatment of nasal discharge” and have no sexual significance at all.

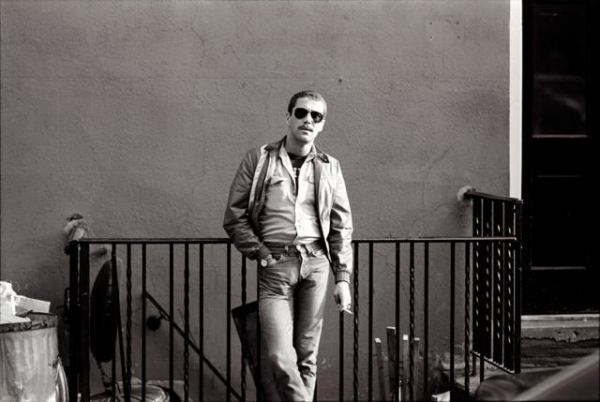

The handkerchief image and the rest of Fischer’s series are on view at Cherry and Martin Gallery through February 21, and it’s the first time the whole series has been seen together since 1977. A vitrine to the right of the door includes Fischer’s Gay Semiotics book and other ephemera related to the photographs he took in San Francisco, particularly the Castro District. On the wall, the photos hang in staggered groups, usually by category (Fischer had divided his images into groups: Signifiers, Archetypal Media Images, Fetishes, Street Fashions). Three Archetypal photos depicting leather and S & M stereotypes, hang in a line beside a cluster of three Fetish photos, including one of a man in a gag mask.

It’s funny how quickly these photographs, exhibited now, read as stylish and attractive. Think of Sarah Conaway’s recent pseudo-vintage black and white images of shoes tied up, or Anne Collier’s 2011 photograph of a 1972 appointment calendar laid out clinically against a white background: the minimal aesthetic of 1970s conceptual photography is itself a fetish, its deadpan directness signifying a certain kind of savvy.

But 40 years ago, Fischer was already poking fun at the apparent savvy of the minimal, descriptive imagery he was employing, and the deceptively deadpan texts are perhaps the best part of his project. Even with a guide to “signifiers” as clear as his, determining what other people want from each other remains impossibly mysterious. In reference to an image of a man with a mustache and stud in his left ear, Fischer wrote, the “stud is often adopted by non-homosexual men, thus making the earring the most subtle of homosexual signifiers. “