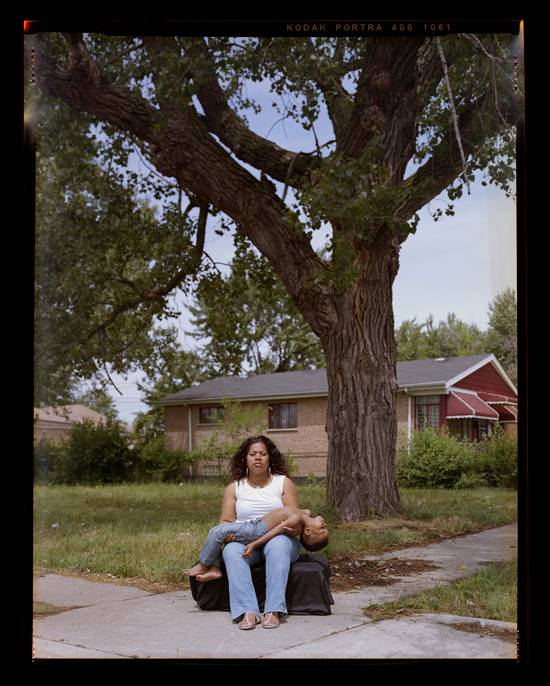

The photographs in Doug Hall’s exhibition Bodies in Space, on view at Bonni Benrubi Gallery through July 25, embody a quintessential contradiction of modern life: While we are part of and shaped by our environments, we are increasingly living within our own worlds of distraction and fantasy.

This seems most evident in Hall’s photos of tourists. Whether they’re at Yosemite’s Glacier Point, Rome’s Piazza della Rotonda, or Mount Rushmore, they’ve assembled, presumably, out of a desire to view the oft-disseminated stuff of advertisements and postcards. Yet in Hall’s photos, they appear oblivious to their surroundings, preoccupied by cameras or cast adrift by a place utterly foreign to them. In the Rushmore photo, the irony is especially pointed, as the monumental, stone faces in the background are the only ones whose attention seems fully focused.

Across the images in Bodies in Space, people look but don’t see, they’re present but they’re not fully there, and they inhabit a reality that seems not quite real. With a flat background and an artificially lit foreground, portraits of a “weekend cowgirl” in Stagecoach, Nevada, and a man in traditional garb at Monument Valley look like the vintage snapshots of a novelty photo studio. Places, through Hall’s lens, have a similarly disorienting artificiality: in Gene Autry Rock, the scene has the appearance of a painted backdrop at a museum or zoo.

Frequently, Hall’s work addresses our relationship to images more literally. His Arrangement #5 of nine photographs from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, though positioned in a crowded, inelegant cluster, speak to the strange, circular ballet of watching, failing to watch, and being watched that occurs in a space where art is presented. In a few photographs, museumgoers (mostly women) look down and away at placards and maps, their eyes anywhere but the art itself. Meanwhile, the works they appear to be ignoring, like Gustave Courbet’s Woman with a Parrot, are themselves studies in spectatorship. That we are viewing all of these scenes through the perspective of Hall’s camera adds yet another dimension to this already intriguing collage.

Another photo shows a man in a gallery in Rome’s Galleria Corsini by himself. It is a double exposure, so we see him twice, each time a ghostly figure gazing passively at the old paintings. For the viewers standing in Bonni Benrubi Gallery looking, likewise, at art, Hall’s perspective resonates: our lives can feel fleeting, but some images are eternal.