On the surface, the two bodies of work in Sunil Gupta’s exhibition, Out and About: New York and New Delhi, on view at sepiaEYE through December 20, have a lot in common. In both Christopher Street and Mr. Malhotra’s Party, Gupta explores queer presence in public spaces. But context is crucial, and ultimately the series, separated by place and more than 30 years, reveal key differences, opening up an intriguing conversation about freedom and identity.

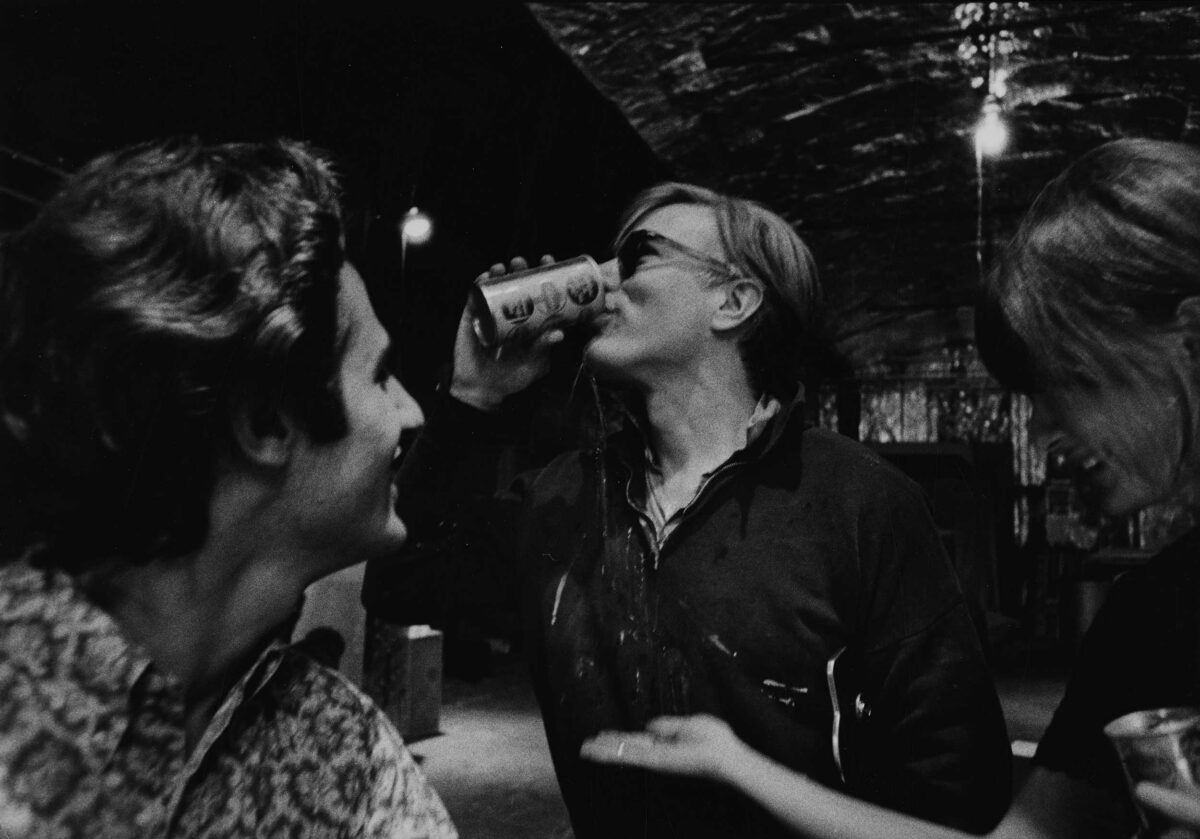

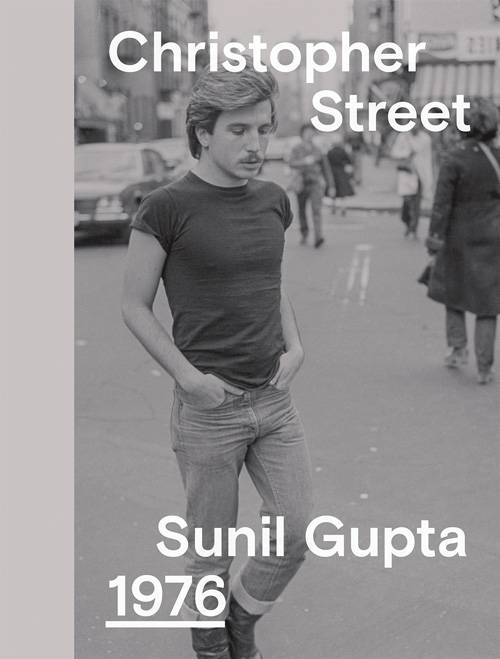

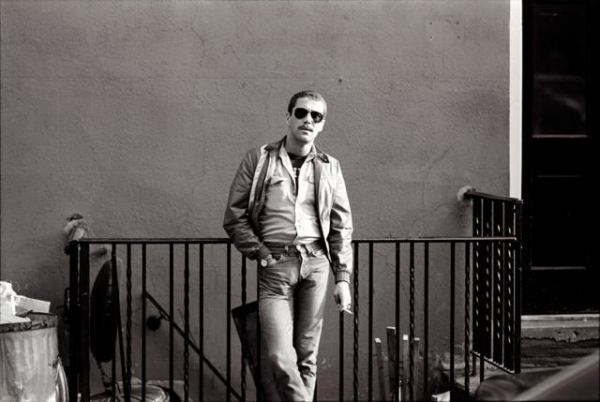

Christopher Street, like much of Gupta’s work, straddles the personal and the political. In 1976 Gupta abandoned a master’s program in business administration in New York City to pursue photography education at the New School. His photos of fellow gay men on Christopher Street from this period may be seen not only as a reflection of the gay liberation movement taking hold at the time, but Gupta’s own “coming out” as an artist.

The Village was a revelation to Gupta, who’d never seen a place where sexuality was so openly expressed. His enthrallment shows in his photographs, in which his camera acts as a proxy for his own wandering, curious eye. His subjects, pictured in black and white walking the streets of the gay haven, are mostly unaware that they’re being photographed, and perhaps equally heedless of their own unprecedented freedom.

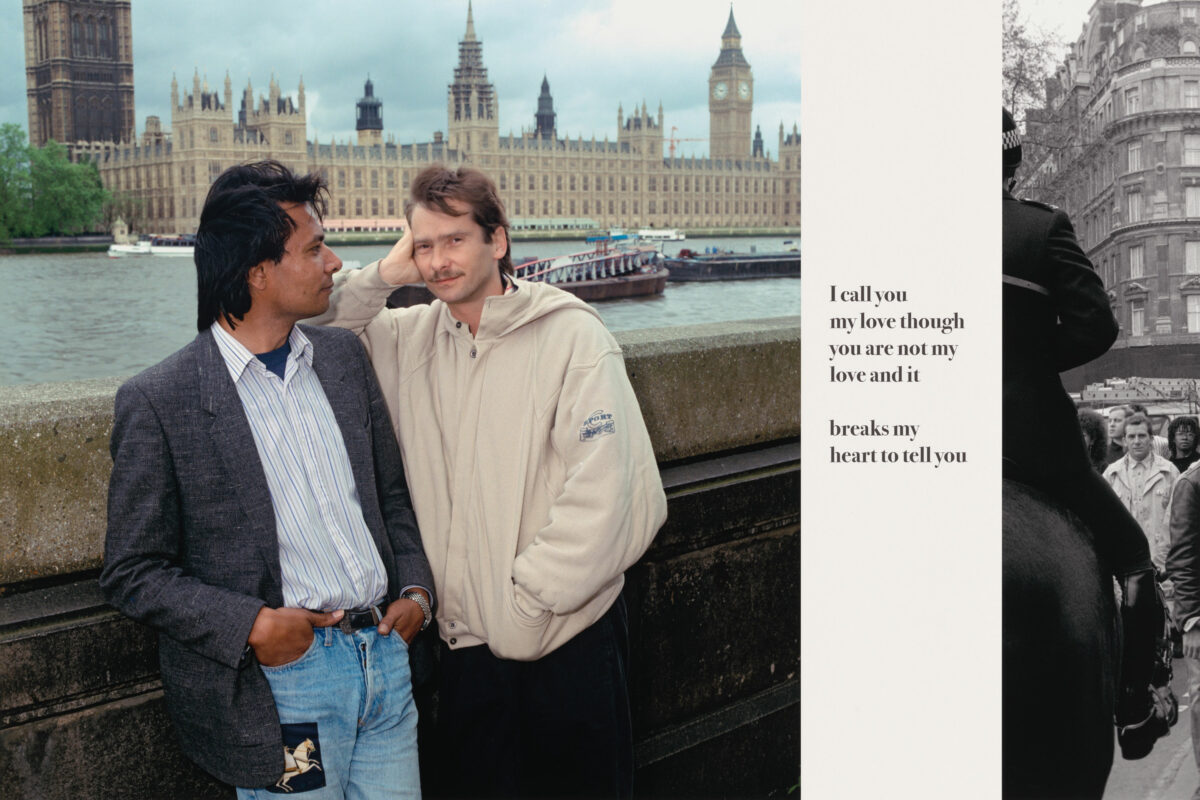

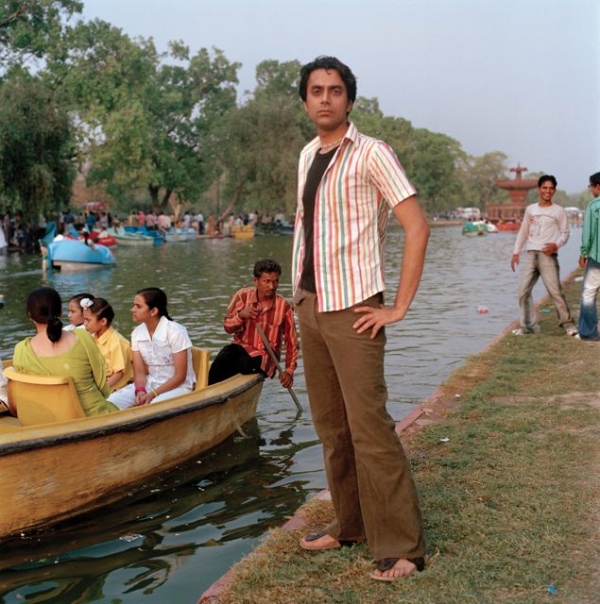

Mr. Malhotra’s Party, taken more than 30 years later, reveals the luxury of that freedom by comparison. In Delhi, where the photos were taken, centuries-old anti-sodomy laws were only struck down in 2009, two years after Gupta began taking photos of queer people around the city (the laws were re-instated in 2013). There are no gay bars in the city; gatherings for queer people are advertised as private parties under the name of a host.

In this political environment, a queer person posing for the camera is a conscious act of defiance, one that Gupta instigated with friends and acquaintances for the photographs. His subjects face the camera directly, as though challenging those who oppose them. Their expressions are powerful and moving.

Taken together, these photos speak to the variety of experiences in gay communities, but they also tell a story about the development of a photographer and activist. While he is an anonymous, wide-eyed observer in the Village, Gupta shows himself to be an active dissenter in Delhi, driven to create a world in which, one day, perhaps, images of gay life in the West and the East might not look so different.