The title of this exhibition, Desire Paths, on view earlier this year, is a term coined by French philosopher Gaston Bachelard to refer to the routes trod into the landscape by habitual use, as opposed to those circumscribed by roads or sidewalks. A desire path is a record of the way people are compelled to move through a particular place, and both artists in this exhibition were compelled to repeatedly trace a path through Hale County, Alabama.

Hale County is situated in Alabama’s Black Belt, so named after its rich soil. In the 19th century, that soil translated to the global business of cotton, produced by enslaved Black people, and thus the moniker absorbs more meanings. Black people still make up the majority of the county’s population. “Hale County” also summons images for anyone versed in 20th-century American photography. Indeed, Hale County has become a signifier for rural poverty, albeit primarily the poverty of white people, and there is no more famous work from that place than Walker Evans and James Agee’s book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941).

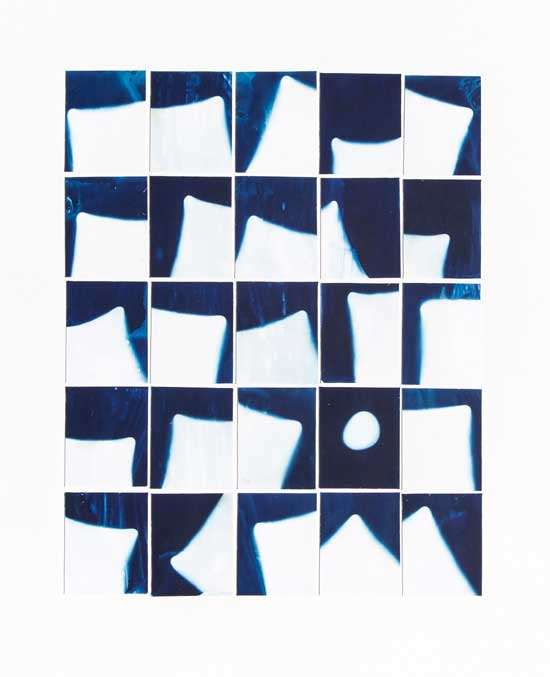

Christenberry, a white Tuscaloosa, AL, native who frequented family farms in nearby Hale County, studied painting and sculpture in the late ’50s but, inspired by Evans’s photographs of vernacular architecture, soon began making the photographs for which he is most famous. His path through Hale County is marked by duration and seriality. Two grids in the show feature his return over the course of years to particular buildings he loved. Green Warehouse, Newbern, Alabama, comprises 21 prints made from 1974 to 2004. There’s a searching quality to the photographs; we see Christenberry probing, trying to unlock the building’s status as a personal icon by varying his distance, perspective, and composition, all while the building gradually weathers in the Alabama sun. His charming sculptural replicas of such buildings, presented on a plot of red Alabama earth, further exorcise this persistent vision.

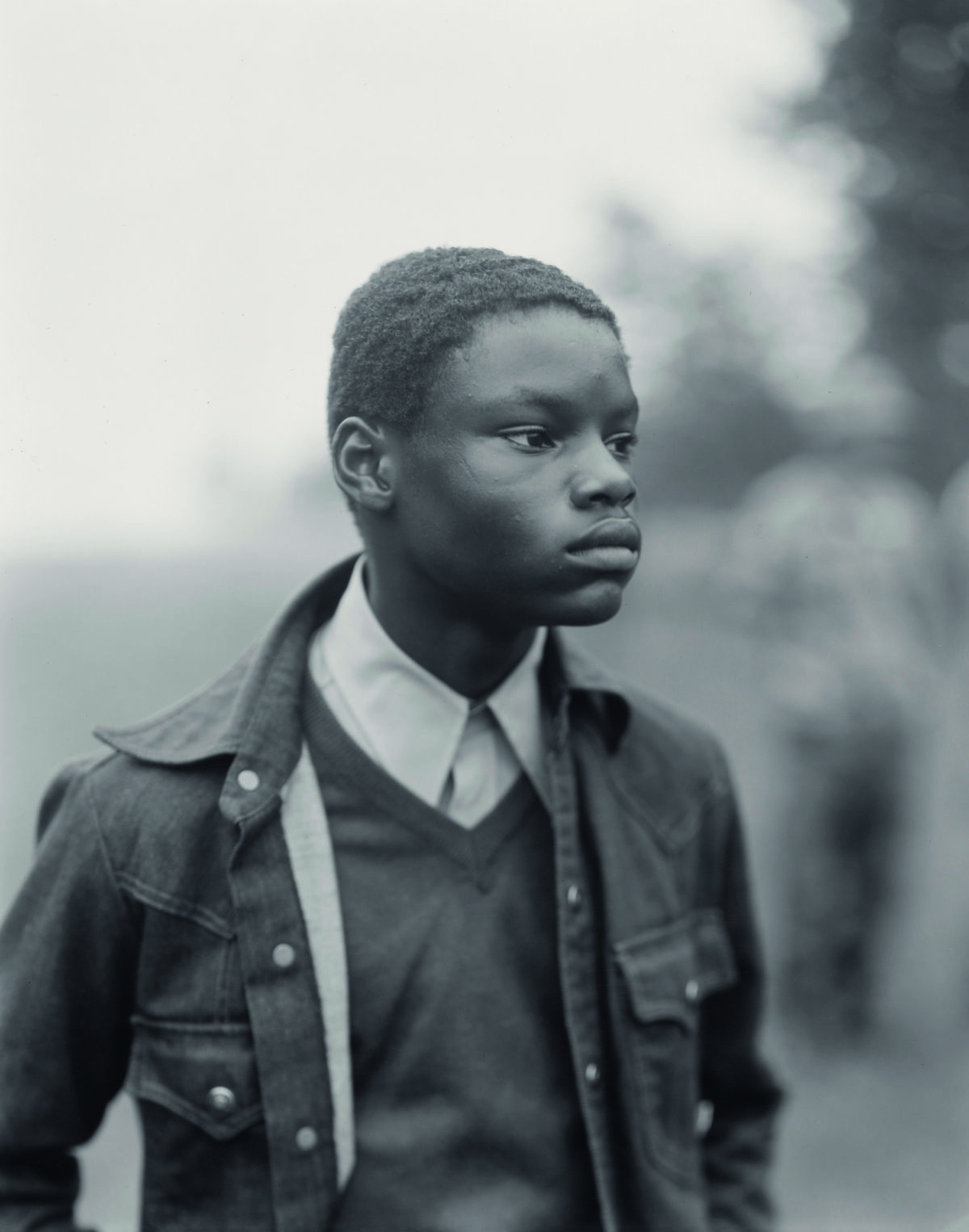

In contrast, several of the photographs Ross presents in the show are of human subjects, though he often makes pictures in which their faces are obscured. The impulse in this obfuscation was also evident in Ross’s Oscar-nominated film Hale County, This Morning, This Evening (2018), in which we get to know a Black community through beautiful moments strung together in a non-linear fashion. This purposeful artistic strategy, of avoiding framing Black subjects in an easy-to-read narrative, confronts the problematic representation of Black subjects in our photographic history.

Ross is also forging new paths in his practice, presenting framed 3D works that, like Christenberry’s, utilize Alabama’s red dirt, as well as a startling multimedia installation, Return to Origin, a documentation of a performance in which Ross shipped himself in a wooden crate over 1,200 miles, from Providence, R.I., where he is a professor at Brown, to Hale County. The work refers to Henry “Box” Brown, who in 1849 famously escaped enslavement this way and went on to become a noted abolitionist. Inside his shipping crate, Ross occupied himself by transcribing his childhood dictionary on the interior walls, inserting the word “black” before each term (black ablaze, black able, black abloom, black ablated). This absurdist gesture points to the construct of race: it is ultimately meaningless, and yet we tend to frame all human experiences and identities within it. In this piece, Ross, confined and transient, transforms a lexicon to reflect Black American experience, an impulse that drives all of his work in this show.

Return to Origin is situated behind a freestanding room that houses Christenberry’s infamous Klan Tableau (1962–2007), an installation that confronts the fearful image of the embodiment of violent white supremacy that haunts our country. Inhabiting its own windowless cell in this exhibition, Klan Tableau is crowded with Christenberry’s dark drawings, groupings of enrobed dolls, confederate flags, and a glowing white cross. Klan Tableau is fittingly prohibited from overshadowing any of the other works in the show; one enters the built space from one doorway, and exits through another, a one-way trip through this claustrophobic hellscape.

Christenberry was born in 1936, the same year Evans and Agee embedded themselves with white sharecroppers, forever enshrining Hale County as both a lyrical and stark emblem of white rural poverty. Ross, born in 1982, brings a Black artist’s subjectivity to this storied place, following his desire path, and creating a necessary provocation about what it means to make art about a place.