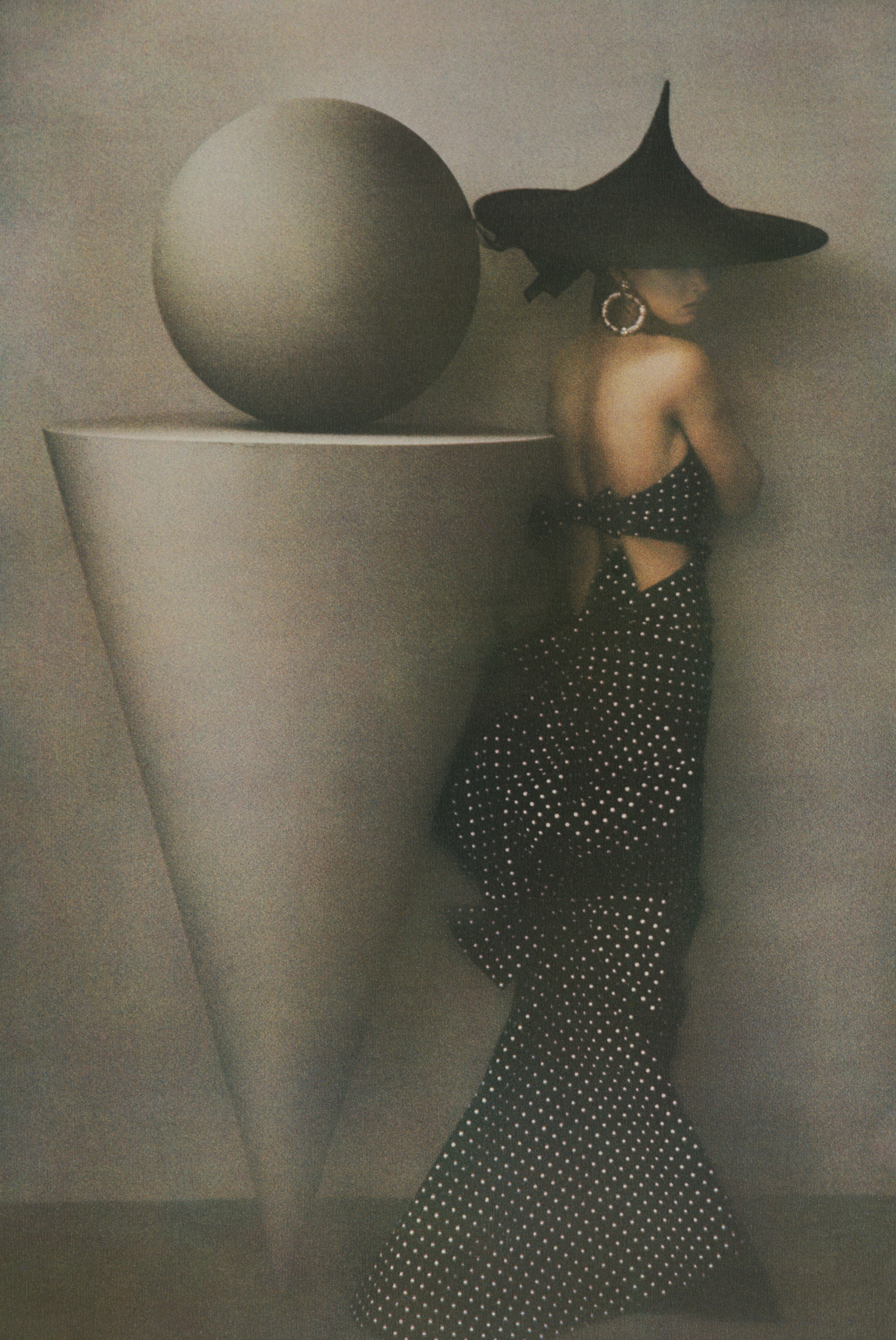

Helmut Newton is a formidable influence in contemporary photography. His work shaped the zeitgeist of the late twentieth century and chaperoned an erotic narrative, once secret and marginal, into the mainstream libido via the newsstand. The photographs helped to secure fashion photography as a genre of cultural significance, not to mention complex fabrication – and very often, humor – which would guide much “fine art” photography.

Newton is a provocateur. Concurrent to emerging feminist thinking, his photographs have been commonly accused of objectification and misogyny; described as “clamorous and unsavory” by no less an authority than The New York Times’s Hilton Kramer in 1975. More longstanding is a consideration of the work as a diorama of class narrative and economic clout. The Newtonian hauteur is the swagger of privilege, of aristocratic aloofness as prerogative, and the sexual servility of the domestic class, uniformed indeed.

A survey of the work on view through May 1 at the burgeoning Marta Ortega Pérez (MOP) Foundation in the handsome port city of A Coruña, Spain, is a seductive overview of Newton’s sensibility from the 1960s until his death in 2004. His vocabulary advanced from German expressionism to a visual language influenced by his annual winter residences in Los Angeles: from the nocturne of Brassai to the frolic of Lartigue.

Curated by Philippe Garner, Matthias Harder (director of the Helmut Newton Foundation) and Tim Jefferies (head of Hamiltons Gallery), Fact and Fiction is engrossing theater, its elegant staging a match to Newton’s showmanship. The darkness of the exhibition rooms feels clandestine, and the spotlighting of each individual image gives an appearance of illuminated screens referencing, if unintentionally, cinema. To its credit, the curation identifies the commissioned source of the image, and the inclusion of magazine pages, Newton’s scrapbooks, and notes from photo editors maintains the significance of the pictures’ commercial roots. It is useful to understand that most of Newton’s work was commissioned by popular magazines, often to accompany conventional subjects (a photograph for Vogue to illustrate aging knees depicts a heeled and lingerie-clad woman scrubbing blood from the bathroom floor) and to speculate whether the work would find such patronage in a present that, paradoxically, seems more restricted by frail sensitivities.

The Helmut Newton lexicon of mischief is present and accounted for: strapping nudes shod in stilettos and with breasts that were then termed pert; anonymous yet swank gentlemen; red meat and riding gear; patrician bric-a-brac; extravagant jewels; sinister and sideway glances; and more black leather and lingerie and furs than one’s neighborhood fetish shop. Polymorphic couples loitering in alleyways and halls. What might seem mannerist now was an act of lascivious insurgence. Newton understood the power of ambiguity to prolong one’s attention, and that, unlike cinema, a still photograph is inherently fragmentary. The pictures’ lack of resolution and explanation contributes to their sexual charge.

The portraits feel revelatory, with nuance and pathos not otherwise residing in the faces from Newton’s fashion work: the vulnerability and discomfort and shiny nakedness of Gianni Versace supine in upholstered opulence; Yves Saint Laurent as marionette; a wan and bespectacled David Bowie resembling a theology student; Karl Lagerfeld as Teutonic carapace. And Margaret Thatcher looking more uncertain than triumphant.

Standing sentinel, the Big Nudes loom like caryatids, a rhetorical device of redundant aggression lacking the thick narrative of place that propels much of the work. Much more fascinating is a grouping of five images of women (from different assignments) in haute couture striding forth purposefully, their significance ratified by the photographs’ paparazzi texture. Of note as well is a collection of 27 Polaroids that introduce the exhibition and are buoyant and lively, sharing a sense of spontaneity and event.

Historically, photographic purpose was split between public and private, family snapshots versus advertising images, and neatly corresponding to the strict expectations of social disclosure and behavior. The last 30 years has witnessed a startling erosion of such certitude, compounded by social media and the pathology of “sharing.” In hindsight, it is instructive to understand Newton’s work in this dynamic and his shuffling of the erotic mis-en-scene. For Newton, public and private are not dichotomous but overlapping – notice his use of the balcony as a fulcrum between the two. Sexual pleasure occurs not in seclusion, but in furtive public moments and in piercing the opacity of wealth. Perhaps this is the work’s most enduring legacy.