In a 2011 interview with the now-defunct Visura Magazine, Larry Fink recalled the approach to life recommended by his mother, a one-time Marxist. “Why sublimate your need for elegance and joy and class and style and fun…I am going to live my life as fully as possible.”

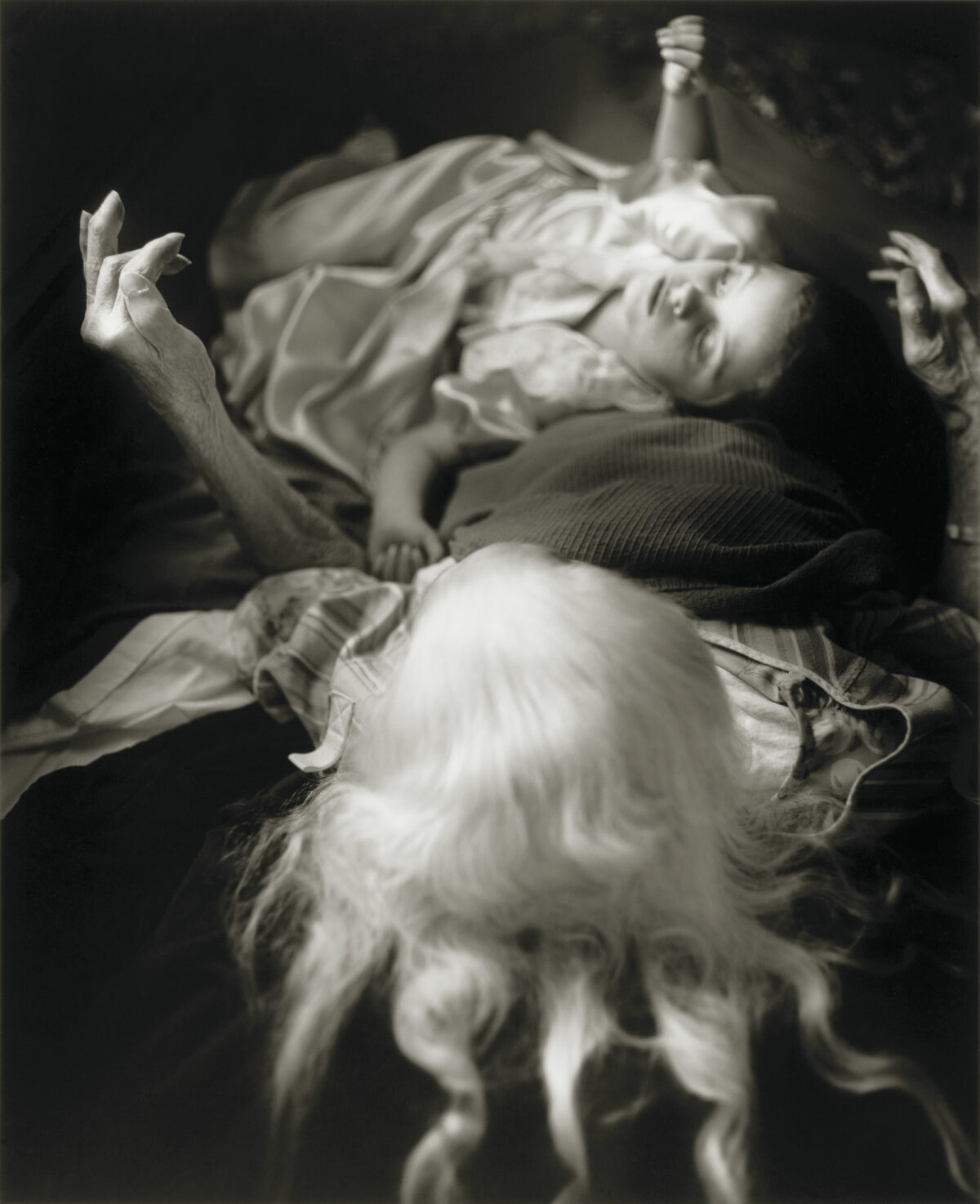

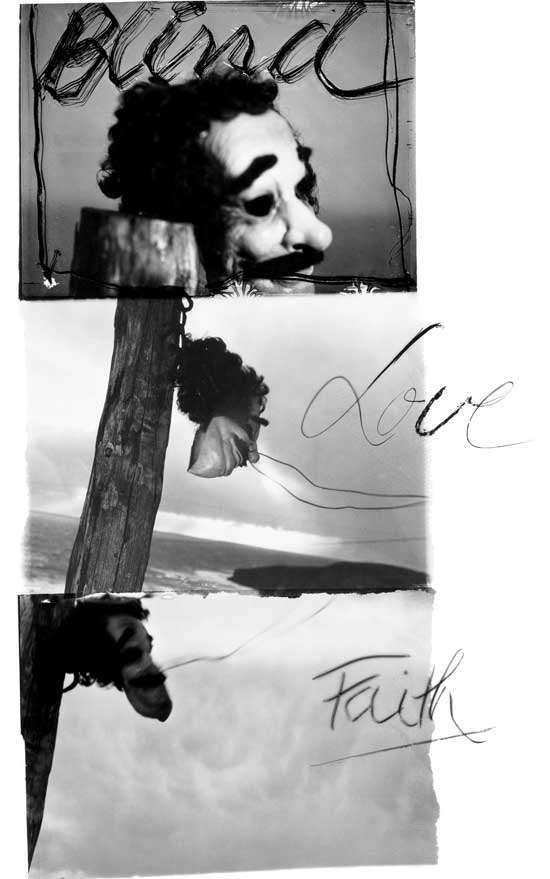

Fink has sought that fullness throughout his long and varied career. As a teenager, he left his family on Long Island and arrived in the Village, where he studied with Lisette Model. He photographed Amiri Baraka and others, whom he called “delusional revolutionaries,” and travelled cross-country with them. Eventually, he settled into life on a working farm in Pennsylvania, home base for his work as a photographer for Vanity Fair, the New York Times, and GQ, to name just a few of the many publications who have published his photographs. He’s won countless photography awards for images that focused on everyone from soigné high society elites to Pacific Northwest loggers. One relative constant has been his use of a hand-held flash, a spotlight to direct the eye. Another is his compassion, hardly solemn but impossible to miss.

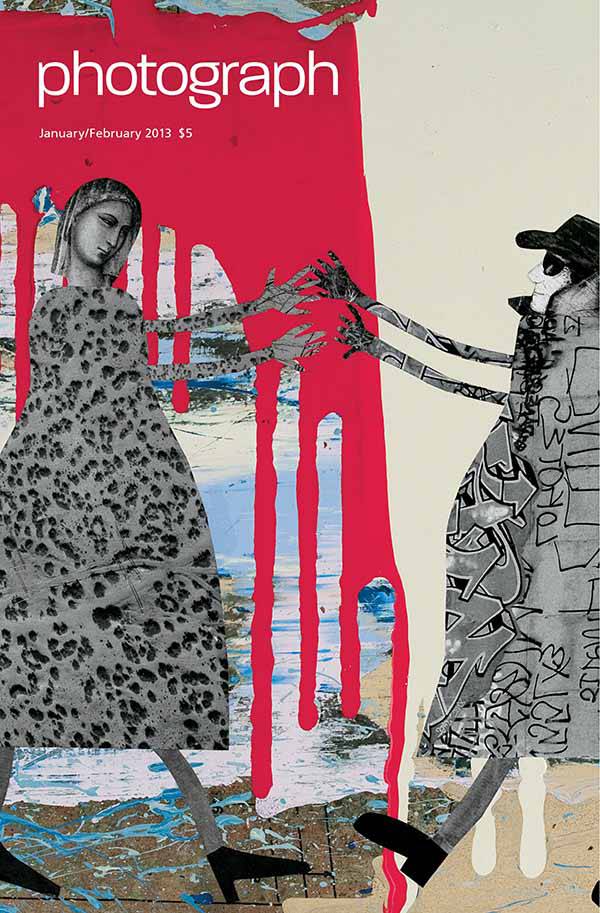

The Robert Mann Gallery represents Fink now, and to celebrate, the gallery has mounted a small retrospective, a sort of introduction, should one need it. The self-titled show, on view through March 4, presents 18 images, many drawn from his influential books, including Social Graces and Boxers. Each is an intimate triumph.

Some feature his Pennsylvania neighbors, the Sabatine family. In Pat Sabatine’s Eighth Birthday Party, Martins Creek, Pennsylvania (1977), a matriarch navigates a birthday cake through a screen door and into a scrum of carousers. They’re all having a great deal more fun than the couple in English Speaking Union, New York, New York (1975), dancing beneath a crystal chandelier. A hand clutches what might be a radio in the window of Staten Island Ferry, Staten Island, New York (1975). Its sense of mystery recalls the avant-garde composer and disco producer Arthur Russell’s love of taking that ride to watch the waves and contemplate his disco compositions – one of which may have inspired the merrymakers in Fink’s Studio 54, New York, New York (1977), who are twirling along in blissed-out reverie.

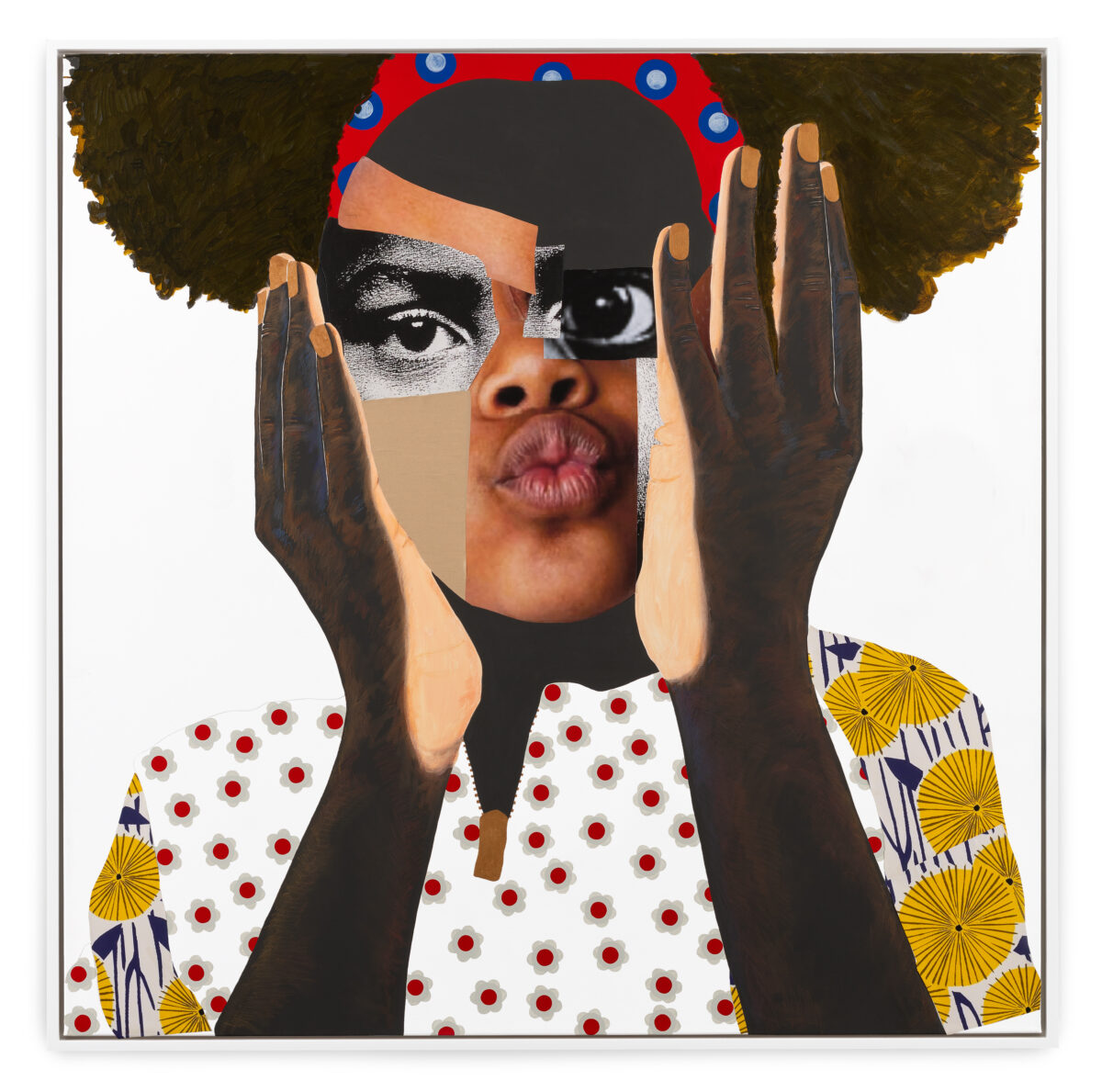

Fink has a facility for photographing Black people, for lighting their skin faithfully and conveying their humanity without condescension or exoticism, qualities not always found in his fellow white photographers. John Coltrane (1962) looks like the jazz giant sounds: abuzz, aglow, in the pocket, out of this world. The boxer in Blue Horizon, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1994), in his satin shroud, is part myth and part martyr, but the sweat on his skin also conveys all the effort his employment demands. Fink has an eye for class markers, from the soft chiffon elegance of the young women at the Second Hungarian Ball, New York City (1978) to the thick overalls worn by a logger in Camp Grisdale Shelton, Washington (1970). In this way, he was a fashion photographer, too.

In the Visura interview, he said his work was “meant to be political, not polemical. It turned out to be not necessarily kind, but certainly honest. And not cruel….I really do embrace – or try to embrace – the souls of all people.”