Judith Joy Ross once asked her mother what she did when Ross and her brothers misbehaved when they were children. Her mother told her that she “would look at us very, very hard, not to stare us down, but rather to look until she truly saw us, and who we really were to her.” In this way, at least, Ross is her mother’s daughter. For close to 50 years, she has looked very, very hard at people, through the lens of her 8×10-inch view camera, until she has seen who they really are to her. Ross’s portraits are not about peering into someone’s soul; they’re about making a connection with the person in front of her camera. That connection – fleeting but profound – is her real subject. “Both of us together,” she has said, “we make the picture. We might actually be in love for a few seconds.”

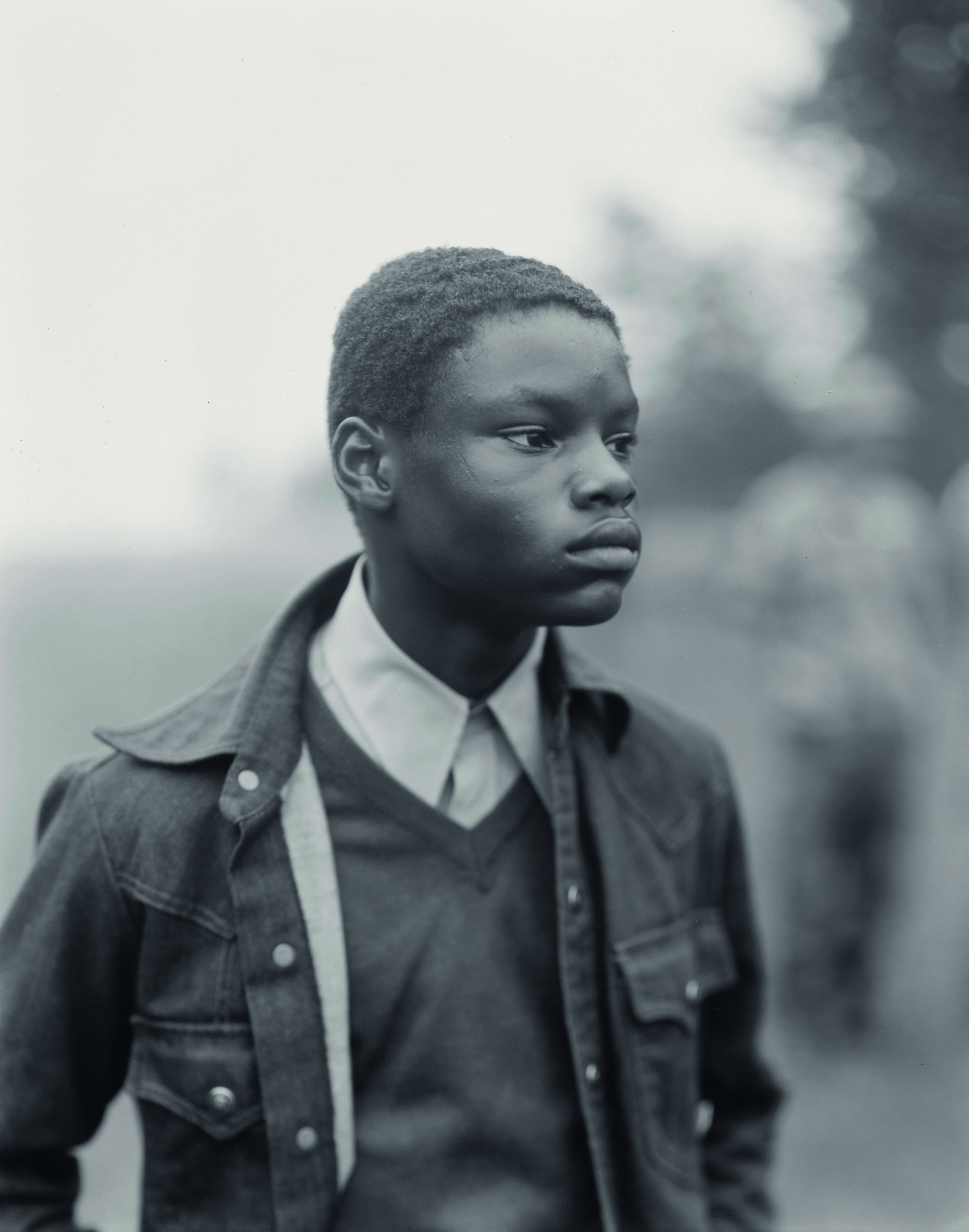

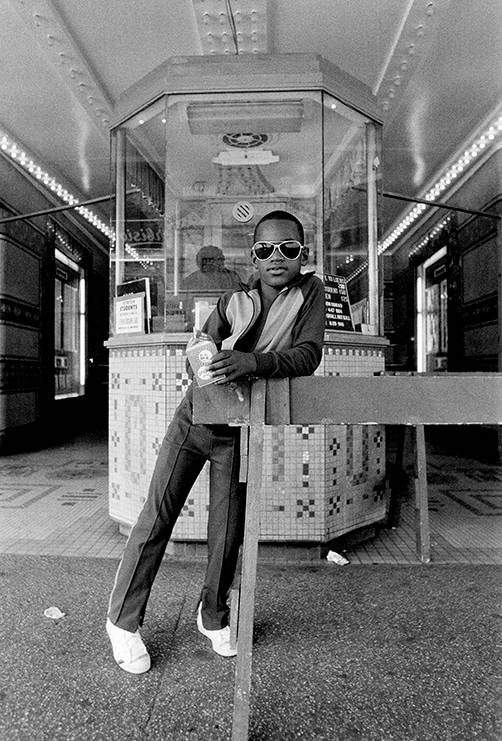

Whether she’s photographing young people at a Pennsylvania park in the summer; schoolchildren in Hazleton, PA; visitors to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC; or US Army Reservists, her portraits are tender, but wholly unsentimental. Even the grinning towheads in Easton, Pennsylvania (1990), are hugging so fiercely it veers toward a choke hold. Ross is drawn to ordinary people, but there’s often something slightly off beam about them, whether it’s the awkwardness of adolescence (the girl in the too-big glasses in Untitled, Eurana Park, Weatherly, Pennsylvania [1982], crossing her arms protectively in front of herself) or a sleeping newborn with the scrunched face of a little an old man (Newborn, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania [1986]) or a smiling second-grader who seems dressed for a day at the office (Jackie Cieniawa, 2nd grade, A.D. Thomas Elementary School [1993]). With the exception, perhaps, of her pictures of members of Congress, Ross’s portraits call up a fierce sense of protectiveness (in me, least). The people in her pictures are imperfect and ordinary, vulnerable and beautiful.

Ross’s portraits share some DNA with August Sander’s People of the Twentieth Century, an early influence. Her series Jobs – including gravediggers, volunteer firemen, and a car salesman – comes closest to Sander’s occupational portraits, though she isn’t interested in documenting societal archetypes. There’s some overlap, too, with the portraits of Diane Arbus, but where Arbus embraced society’s “freaks,” Ross has been drawn to the ineffable qualities in everyday citizens. “People are beautiful. Period,” she observed. There’s a quietly transcendent quality in her photographs that has to do with the way she processes her prints. Using printing out paper (which has been discontinued), Ross toned her black-and-white prints in gold chloride, which lends them a grey or a brown tone and imbues them with a rich emotional register.

More than 200 of Ross’s photographs are on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through August 6. Although this retrospective exhibition, which was curated by Joshua Chuang, opened at the Fundación Mapfre in Madrid in the fall of 2021, the Philadelphia Museum is its only U.S. venue. It’s a homecoming for the Pennsylvania native and a long overdue recognition for someone whose presence, as Vince Aletti put it the New Yorker, “has been flickering rather than steady.” Perhaps this is due in part to the fact that although 16 of her photographs were selected by John Szarkowksi for inclusion in the Museum of Modern Art’s first New Photography series in 1985, Ross has stayed mostly close to home, taking many of her photographs in and around Hazleton, PA, where she was born, and Bethlehem, PA, where she lives. According to Chuang, only a fraction of her work has been exhibited and published – close to 50 percent of the photographs on view at the Philadelphia Museum have not been shown before.

Ross has a gift for photographing children: she doesn’t talk down to them, visually speaking. One of her early series, from the mid-1980s, is Eurana Park, the name of a local park she visited regularly while she was mourning the death of her father. Adults carried too much pain in their faces, she has said, so she set out to photograph young people. It’s not that the children in her pictures are so full of joy – many are quite serious, and maybe a little wary of being photographed, of being looked at so closely. Possibly they’ve paused, dutifully, for this woman with her unwieldy camera, before they can get back to whatever they were up to. But the tenderness she extends toward her young subjects also encompasses a time and place, a quality of innocence. Ross called Eurana Park a sort of Brigadoon, idyllic and out of time. Still, the three girls eating Pac Man popsicles in their bathing suits (Untitled, Eurana Park, Weatherly, Pennsylvania [1982]) will be teenagers soon enough, with all the self-consciousness and self-awareness that comes with adolescence.

In the early 1990s, Ross began a project photographing the Hazleton public schools, which she herself had attended, partly as a way to draw attention the importance of public education. The scuffed desks and peeling paint are clues that Hazleton is a working-class town. Ross photographed the schools as places worthy of consideration and care, with students and teachers deserving of support, from the first graders napping, heads on desks, to the gangly first-year teacher in his rolled-up sleeves who looks like he’s barely out of high school himself. In 2006, Robert Adams wrote about Ross’s Hazleton photographs in an issue of Aperture, observing, “as an American whose country seems in moral collapse – this country having endorsed war and torture as instruments of empire – I find myself focused upon related but slightly different matters: if education is our only hope, the photographs usefully remind us of the basis for that hope – open, innocent children, and caring, if tired, adults.”

Ross’s photographs honor the practice of civic participation – not the bombastic, flag-waving version, but the quieter day-to-day one. Caring, if tired teachers, voters standing in line to cast a ballot, Army reservists on call to serve in the Gulf War. One especially poignant portrait shows PFC Maria I. Leon, from Bethlehem, PA (1990), in uniform, waiting to be deployed. She looks off into the middle distance, preoccupied, I imagine, by the enormity of what lies ahead. (In the exhibition, Ross’s somber portraits of visitors to the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial face her portraits of members of Congress, on the opposite wall, a subtle rebuke to leaders that send the nation’s young people off to fight and die.)

A week after September 11, 2001, Ross went to the Eagle Rock Reservation in West Orange, NJ, which offered a view of the now-empty skyline where the Twin Towers had stood, to photograph people who came there to contemplate the void. She scrawled a message on a piece of notebook paper (which sits in a small glass case in the exhibition) and handed it to people she wanted to photograph: “May I take a photo of you looking towards Manhattan. In 10 min. I must set up my camera.” One of the people she photographed was named, remarkably, Lois Adele America Merriweather Armstrong. In Ross’s enormously empathetic photograph, a few wisps of Armstrong’s white hair have come free, and she’s taken off her glasses, which rest on the barrier in front of her. Ross photographed her gazing ahead at the now radically unfamiliar skyline. She seems to have come alone, just to look and bear witness, something Judith Joy Ross would surely have understood.