The work of French photographer Vasantha Yogananthan is perhaps the most distinctive of a new generation of photographers rethinking documentary. His ambitious multivolume exploration of India titled A Myth of Two Souls (2013-21) gained international recognition for its mix of staged portraits, texts, landscapes, and painted images. In 2022, Yogananthan participated in Immersion, a French-American photography commission by the Fondation d’enterprise Hermès. The result of that project is the recent book Mystery Street, published by Chose Commune, and an exhibition of the same name, of photographs shot in New Orleans. It is on view in Paris, at the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, through September 3 and will arrive at ICP in New York later in September.

Lyle Rexer: How did Mystery Street come to be?

Vasantha Yogananthan: I was nominated for the Hermès Immersion commission, in which a French photographer makes a project in the U.S., and vice versa with an American photographer in France. After I was selected, I made the proposal to photograph in New Orleans. I had been in the United States, in New York, but never photographed there.

LR: Why New Orleans?

VY: Because of movies I had seen and, more importantly, because of a certain collective imaginary of the South as linked more intimately with the natural world – New Orleans and the bayou, for example. Of course, New Orleans has a rich cultural history, but in this case I thought it would be interesting to stay within a narrow environment, to make the city the strict boundary, and work in the summertime. New Orleans is a very specific city, but even more so in the summertime. There is heat and humidity, and people try to get away, so no block parties, no large festivals – the things New Orleans is known for. But there is another reason. I had planned to work with children –

LR: Which you did remarkably in A Myth of Two Souls.

VY: Yes. And I knew that the children I would be photographing, wherever they were, would have been born after Hurricane Katrina, and so would have no vision of the city from before. It suggested a good metaphor for the city after Katrina, an image of New Orleans coming of age in a new way.

LR: These concerns form the story around the project, but I wonder if they come through in the images themselves, perhaps in the way your subjects are framed.

VY: My former project in India was very much centered on the question of what can photography do in the sense of storytelling. How can you combine words and pictures, how can you re-create a fictional narrative? For The Myth of Two Souls, I was working with the text of the epic Ramayana. Mystery Street became a reaction to that. I wanted to let go of the need to tell a story and go back to a way of taking pictures that was very loose, in the sense that you try not to come with preconceived ideas or to direct anything but to be open to situations and accidents – everything that makes life interesting. What I experienced with this group of kids were the most basic emotions that we all know – friendship, love, sadness – as they appeared every day, from morning to evening. The title was simply the name of the street I lived across from for three months – nothing more ordinary and real than that.

LR: But that’s where the mysteries reveal themselves, in the ordinary. You spent your “immersion” with one group of children, presumably in one locale – not in all of New Orleans, not roaming like a peripatetic street photographer. That represents another limiting choice.

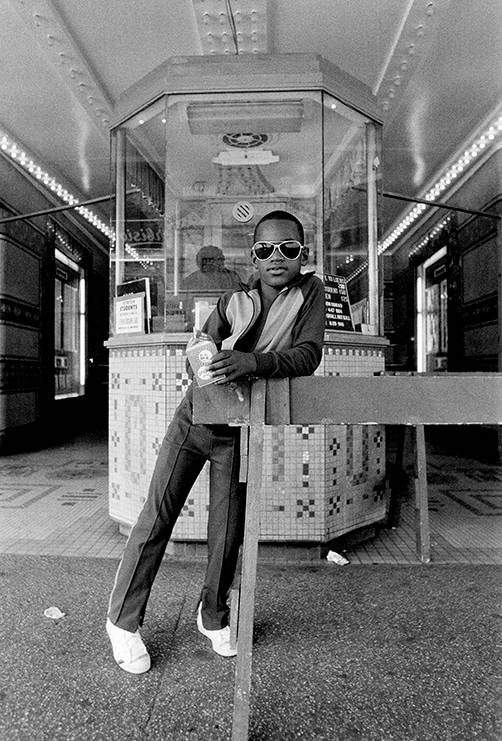

VY: Most photographs are taken in Central City, which is a Black community. There was a summer camp there, a day camp, that provided a focus and agreed to my project. In the evening, the same kids would meet up in a park nearby. So even if three months is a relatively short span of time to spend, by meeting with them every day, I became very close to their world. The first month I didn’t take any pictures at all, just explained to everyone what I was doing there. The second month I came every day and watched. People got used to seeing me, like, “Oh, he’s back again.” I wasn’t going to force the photographs. More than anything, that patience and trust made it possible to make the pictures. Before I started, I also had the hope of looking at play: what does play mean to children? But spending the summer with them made me realize that what happens before and after playing is equally important – the boredom of summer, when nothing seems to be going on.

LR: You must have seemed like something of a strange bird to the kids, with your accent and appearance, never mind the camera.

VY: I think they thought I was Latino. As for the accent, there were times when, because of the street slang they spoke and my strong French accent, we couldn’t understand each other.

LR: I want to return to your idea of an unforced documentary practice. You make very specific choices about how to shoot. Most of the work is tightly cropped, and there are few shots in the middle distance and no establishing shots to set the locale. Timing and gesture are so important to these images.

VY: Oftentimes we speak of the distance between the photographer and the subject, but in this case I attempted always to photograph at the height of the children. One device was to shoot over their shoulders, using a wide-angle lens, which you don’t usually use to make portraits. So I had to get super close, and that created all sorts of problems I couldn’t control, since the children were often moving and creating situations. And by foregrounding everything, it made colors more prominent, often like abstract elements. The images become more about relationships between the subjects. I would call them indirect portraits, where the subjects do not address the camera. There are only a few where the children look back at me as the photographer and none where I pull back to get a landscape. New Orleans is there, but as an atmosphere of color, humidity, and heat.

The photographer Paul Graham has talked about post-documentary, and that resonates. I think my own practice is evolving in that direction, working with the real world and not staging anything but subtracting a great deal. And then when I am back in the studio, working on editing and sequencing, comes the most important part of the process, the decision of what to show or not. And that, along with the sequencing, turns the images back into a fiction. Mystery Street, for all its elements of the real world, is a fiction.

LR: I wanted to ask you a final question about influences. Even in the tight confines of Mystery Street, there are a lot of references. I see traces of Helen Levitt, especially her photograph of the child looking under a car wheel [Girl Playing Under Green Car, New York City, 1980]. But I also can’t help thinking of Francis Alÿs’s wonderful video project Children’s Games (1999-ongoing), and of course the young Lartigue. Some of his best work feels as if it were shot by a precocious pre-teen – because it was. His young world was in constant motion.

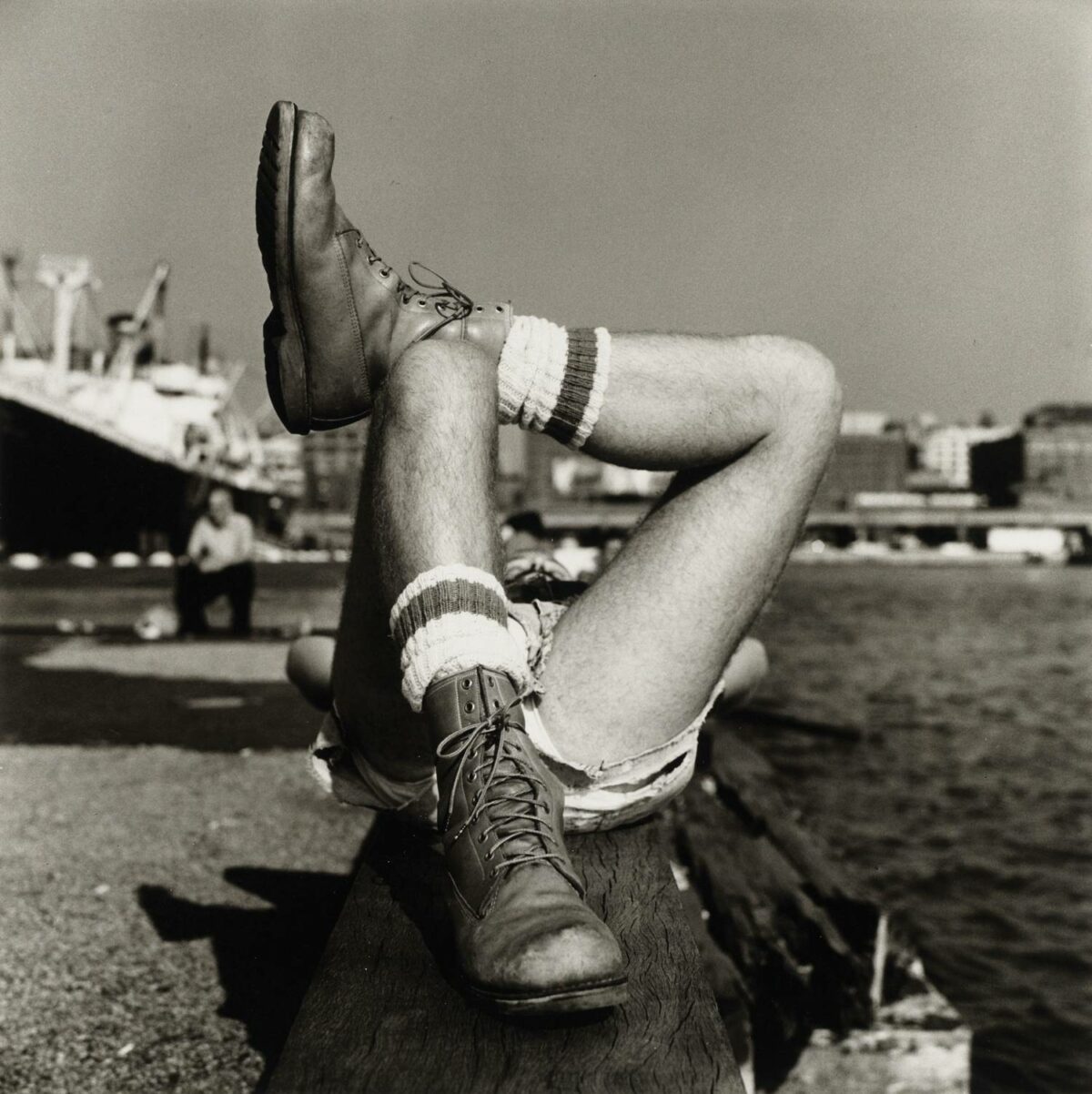

VY: Helen Levitt is the most obvious, but also the beautiful, multilayered imagery of Dave Heath and Sergio Larraín in Valparaíso, Chile. Francis Alÿs has also been a great influence. I have watched all his short films with children and I have all his books – the way he works is so refreshing. In regard to Lartigue, I became so bored with the way I was working, with a large-format camera and setting up images. And when I looked around, I saw that so many contemporary photographers had erased every trace of accident and chance. Everything was conceptualized and worked out as a “project.” But one of the strongest things our medium can do is to capture movement, what is fleeting. Layering together those two elements, precise sharpness and the blurriness of sudden motion, is one of the most beautiful and important things photography can do. The combination of sharpness and motion gives the picture a “vibration,” almost as if the subject is breathing. Photography can not only document what is unfolding in front of the camera, it can exceed that by making us fully aware of the experience of being in time.