If it weren’t for the presence of his own persona, Tommy Kha’s exhibitions could seem like a group show, with self-portraits, collages, still lifes, landscapes, and even family photographs all jostling each other. The diversity of his photographic strategies is on display in his recently published monograph Tommy Kha: Half, Full, Quarter (Aperture). It is a result of the Next Step Award, a collaboration between Aperture and Baxter St at the Camera Club of New York, in partnership with the 7|G Foundation.

Lyle Rexer: I am intrigued by the title of your book as well as by the structure. What is the significance of “Half, Full, Quarter,” and how are the pictures organized?

Tommy Kha: Lesley Martin at Aperture was the first to see the pictures for the Next Step Award. She saw there was a book there. I never thought of my work in book form. She got Alex Lin [of Studio Lin] to design it. She went through hundreds of pictures and saw a throughline but we couldn’t put our finger on it. Lin came up with a way to size, scale, and position what were essentially four bodies of work. I tend to compartmentalize into bodies, but don’t think in series. I think of groups of photos as short films. The title came from our categorizations. “Half” refers to the collaborations with my mother, not only because she is a participant – initially unwilling – but also because I get at least half my DNA from her. “Full” refers to what I call facades, in many of which there appear masks or cutouts of me. And “quarter” refers to the photographs my mother took when she arrived in Canada in 1984.

LR: The book concludes with a whole series of collages, mash ups of family photos and your own work. Where do those fit in?

TK: Lesley Martin kept insisting I write something, and I kept refusing. I did the collages instead.

LR: The challenge for an exhibition or a book is that you work in so many different ways: collage, portraits, performative self-portraits, landscapes, and still lifes. I can imagine viewers may have their heads spinning a bit.

TK: I am happy that people see that there are connections in all this diversity. I see my throughline as performance, with the southern landscape as a backdrop, though this is reductive. The landscapes are more observed, not performative as such, but they provide a stage, and it is sometimes empty.

LR: How did you develop as a photographer? What work did you look at?

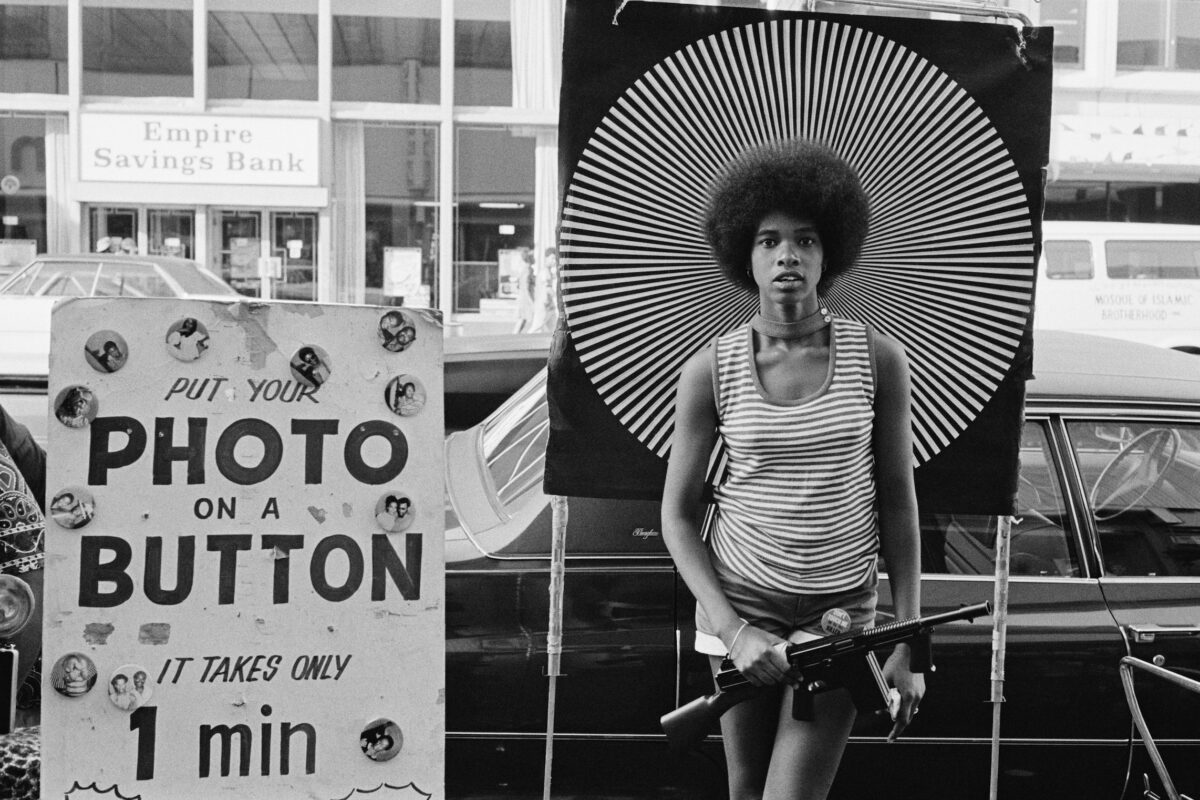

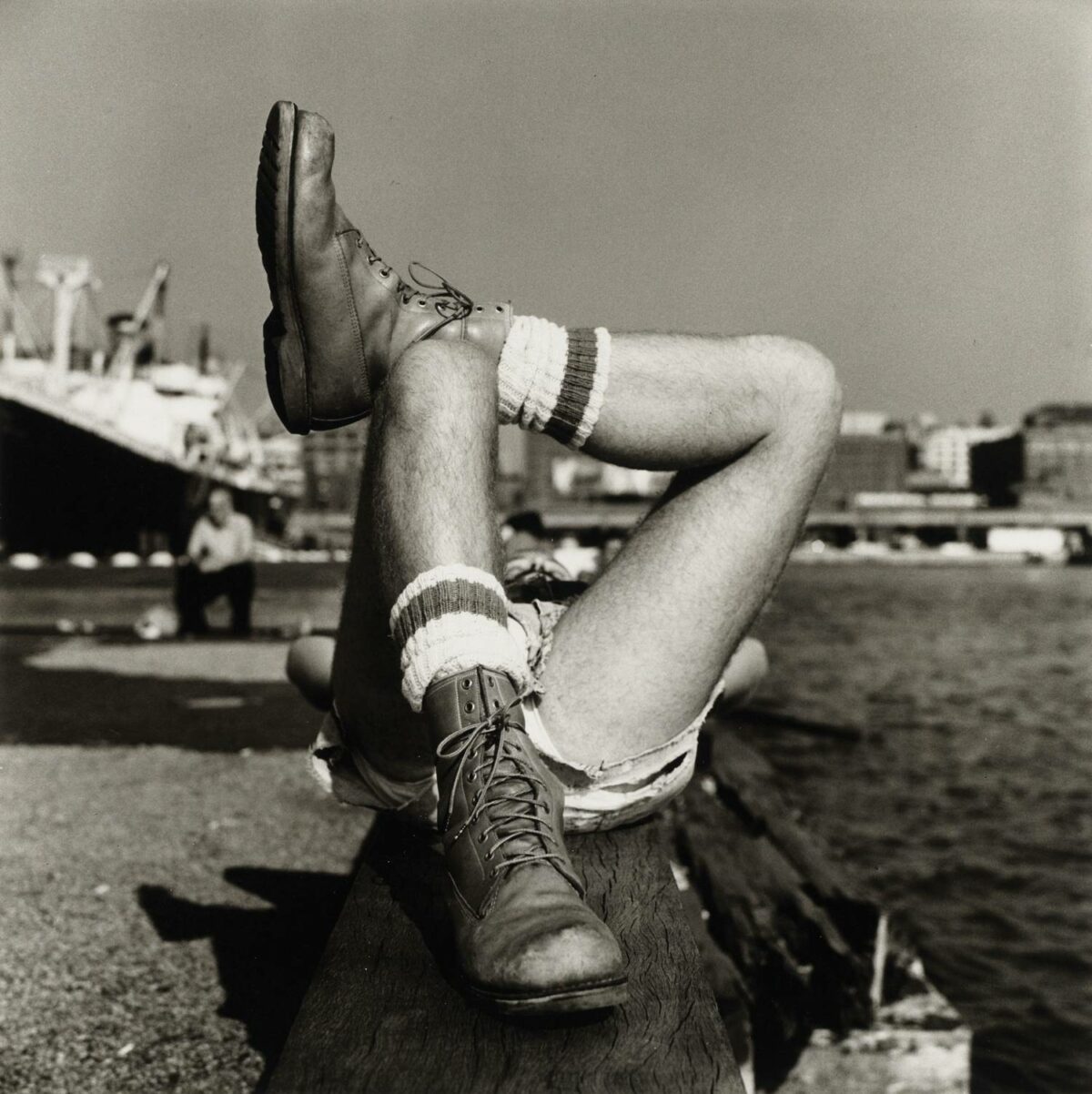

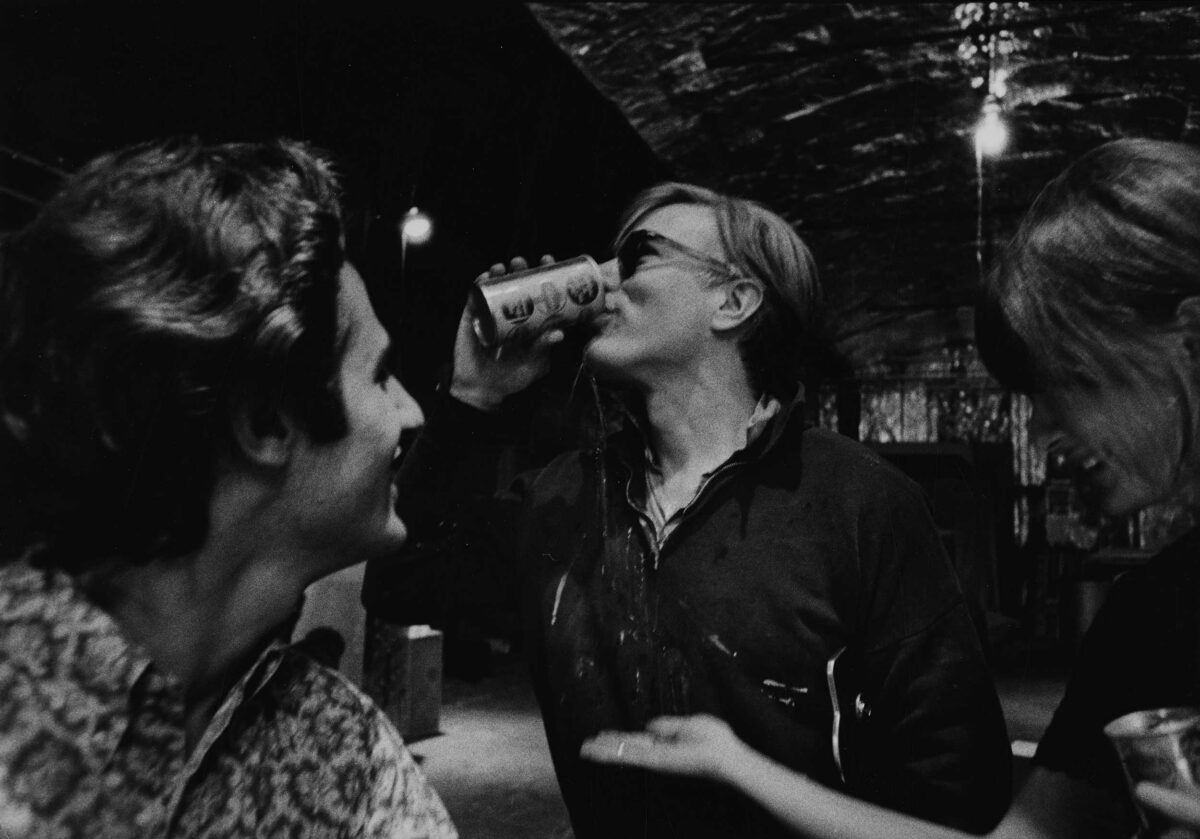

TK: As someone who grew up in Memphis, I am aware of and haunted by William Eggleston’s legacy. We are friends and we spend time just hanging out. He’s a great person, and we never talk photography. We watch Hitchcock movies, for instance, or he talks science. I like that our experiences make us pieces of a larger puzzle. I avoid trying to make work that looks like his. My first thought that I could be a photographer was seeing Sandy Skoglund’s Preventive Adulthood at the Brooks Museum in Memphis on a school trip. Sophie Calle’s work I love. After college [at Memphis College of Art] I applied to Yale and for some reason, I was accepted. This was the last class under the program’s leadership by Tod Papageorge and before Gregory Crewdson. I liked that transitional moment. At the same time, to be doing self-portraiture in a legacy-driven program – Walker Evans was one of the founders of the program – was exciting, and suddenly I found my work being looked by artists I had read about, like Lorna Simpson. I was so embarrassed. And embarrassment has kept me going!

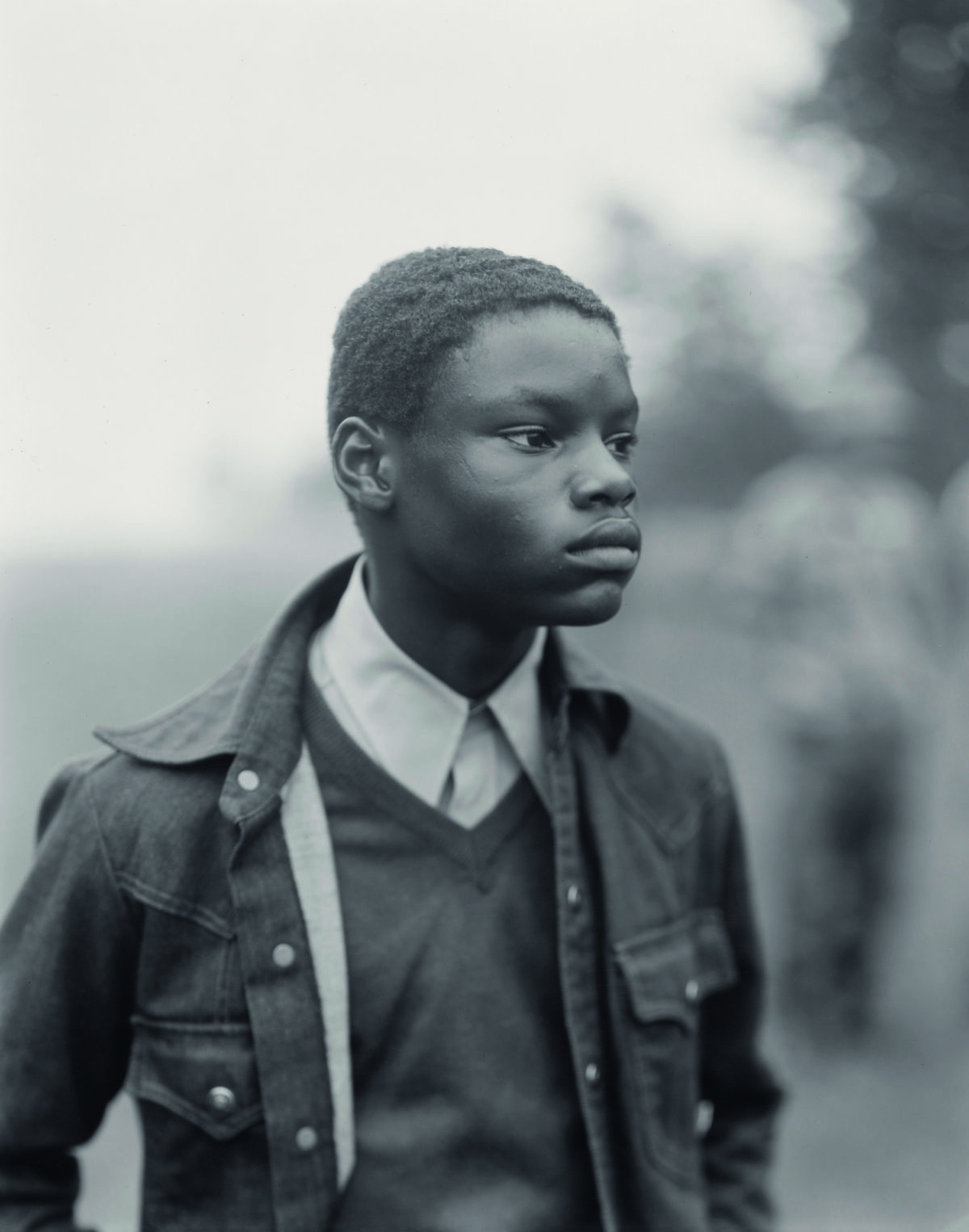

I felt I made terrible pictures at Yale. I think of these as my bad art pictures, and I could not often tell if what I was doing was bad or good, but this was a Rosetta stone for me of languages I would use. When I moved to New York, I met Judith Joy Ross. She looked me up and down and said, “It took me eleven years to make a picture after grad school. Relax and have fun.”

LR: That recalls for me one of the voices you speak in, what I would call the formal informal portrait. You have an ability, when you are staging, to let your subject just be, especially when it is your mother. It is hard to take those kinds of pictures.

TK: I started out photographing people. But knowing what I wanted and planning everything out fell apart so many times that I realized that a lack of follow through or control allows my sitters to move around a bit and be who they are. I want that realness. People are a lot more interesting when they’re not thinking about it. I plan it but leave room to be surprised. I have come to the conclusion that there are good pictures and bad pictures, and then there are my pictures.

LR: Can we talk about your mixed identity? It seems that through all the various formats and iterations of your work, you are seeking a form for the presentation of your multiple selves.

TK: I am a product of a diaspora. Both parents are Chinese and came from Vietnam. I’ve stopped using the word identity. It’s like the word memory, which I have also stopped using. I prefer the expression “time travel,” for that’s what we are doing in a photograph. I am looking for other synonyms for self. At the same time that there is this throughline of self-exploration, this theme is also a disguise. I don’t want to be tied to a strategy or a position. So the cutouts I make become a mask or the masks become cutouts of my hands or temporary tattoos of my eyes. I see this “self” as unaffixed. After all, we change with new information. We shed cells every day and reform them. We go through different crises emotionally.

LR: Some photographic sequences in the book are quite disturbing. For example, a picture of your grandmother in bed, almost deathlike, precedes a photograph of the hotel in Memphis where Martin Luther King was killed, which is now a museum.

TK: My classmates in graduate school said I should not be doing that kind of picture. It made me confront the question, how do you photograph in the south and not acknowledge Black spaces? Should I ignore them? There are many southern photographs being made now and many canons of that photography, not just one. These are sites of conflict, and we need to acknowledge that no one narrative will describe or explain them. I should add that there is a lot of racial mixing in my family.

LR: That raises the identity issue again. How do you resist being typed? The world wants to identify you and your work easily, as Asian, or Chinese or Vietnamese, but your reality is not something that can be boxed up or boxed in.

TK: A Chelsea gallerist once said to me that my work was all over the map, and maybe I should emphasize my “Asianness.” I’m left-handed too, if we want to throw another log on that fire.

LR: And behind it all there is the more fundamental identity: photographer. I wonder if you have developed an overall view of the medium, in all its manifestations.

TK: My own personal theory of photography has three elements. The first has to do with the difference between selfies and self-portraits. Selfies are like mirrors, with their immediacy and ease. With self-portraits there is a distance, a gap, when you set the timer and move back into the frame and compose. Second, photography is a language, and all language is communal, so my photographs are like casting a net to bring others into communication. Finally, for the photographer, photography is a haunting and an exorcism. I am haunted by the past, by predecessors, and can’t help making reference to them when I shoot. At the same time, I have to exorcise the past and get beyond its influence in order to work in the present, to speak in my own voice.

LR: I like the restlessness of your work, that it is always changing. What are you looking forward to?

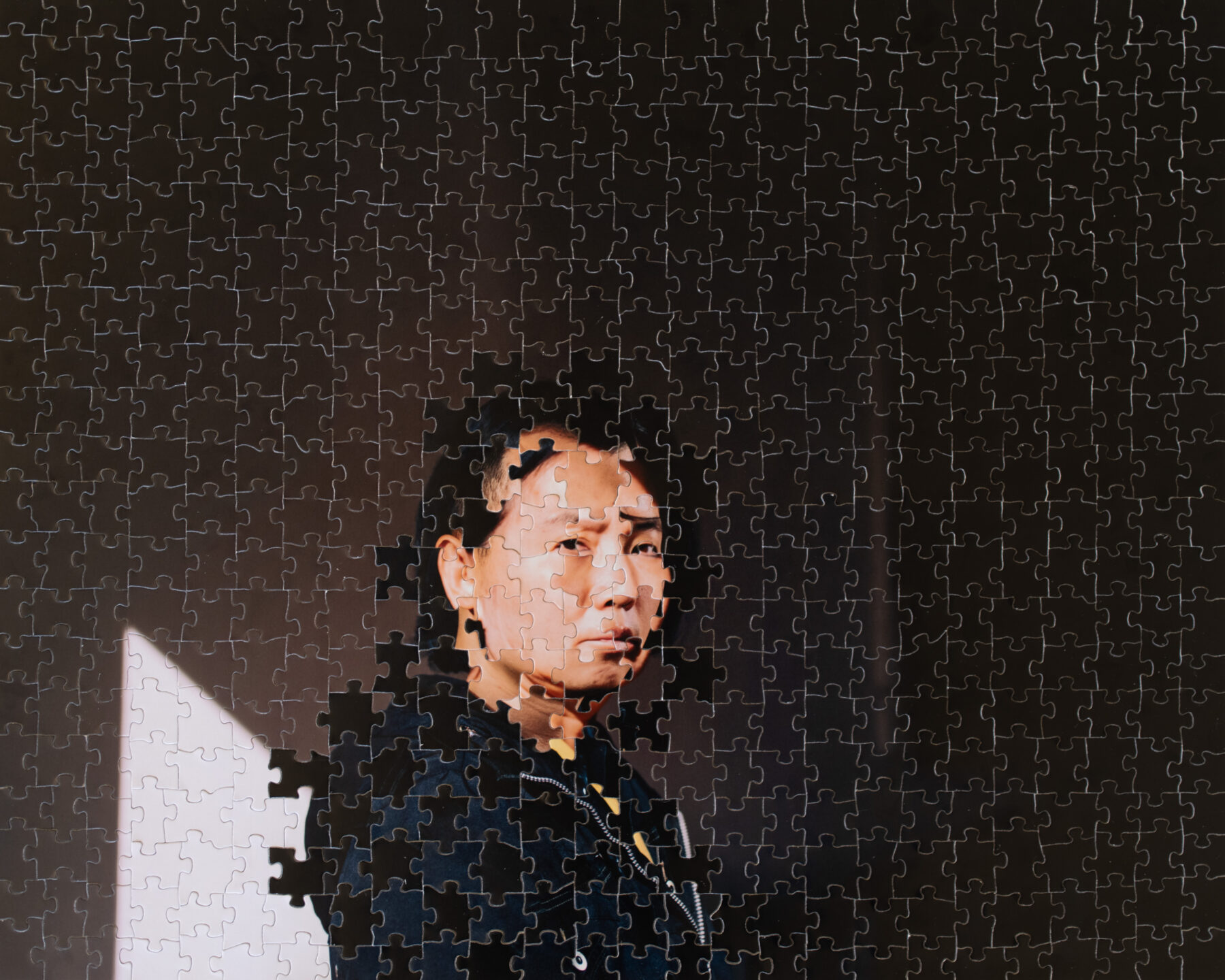

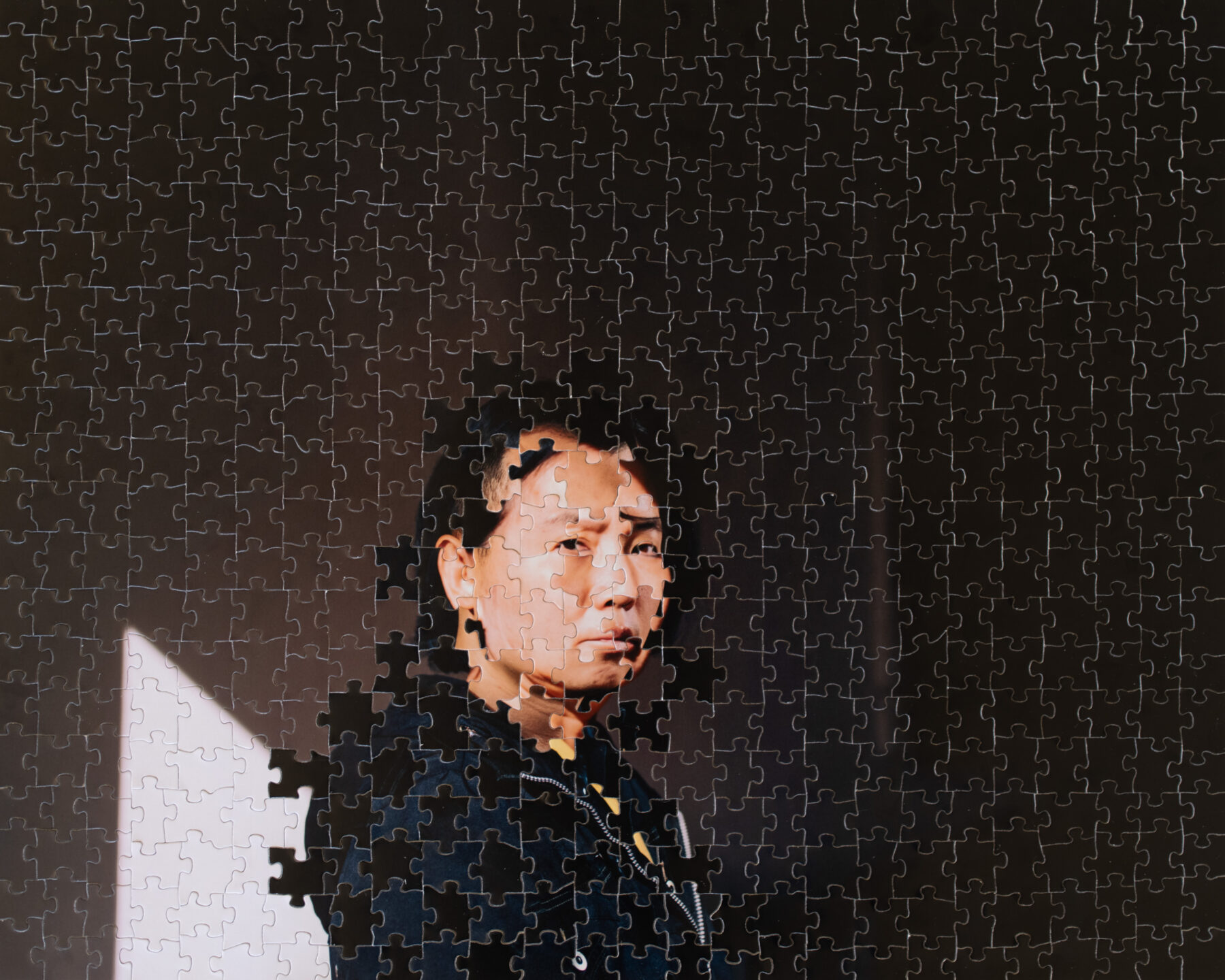

TK: So many things. I’ll be working more with folded pieces on the gallery wall. I’ll do more puzzle pictures, where I transform an image into a jigsaw puzzle. I don’t want to be the puzzle guy, but there is more to explore there. I have also started cutting up my photographs, not to collage them but cutting them in half. And I plan to address more deeply my aunt’s death. She was a victim of domestic gun violence. There are quiet hints of this in the book, but I have never fully resolved it, and now I feel the need to do that.