Since the 1970s, Doug Hall’s work has addressed large power structures, from presidential politics to literal voltage, as seen in his notorious 1987 installation, The Terrible Uncertainty of the Thing Described, currently on view at the San Francisco Art Institute as part of SFMOMA’s off-site programming. His interest in more subtle power dynamics is visible in a compact show of photographs at Rena Bransten through May 16. Working with photographs culled from projects realized over the last 25 years, Hall has composed an elusive, layered meditation on commerce, buildings, and romantic desire—as well as on the artist’s own career.

Hall has taken the physical gallery space– a modest ground-level storefront—as inspiration. He utilizes the shop window to display Olympia of the Department Store, a 1991/2015 C-print of a reclining female mannequin in a swanky but eerily empty retail setting. Nearby Hall nods to Walter Benjamin in The First Chapter, 2015, a slightly larger-than-life image of an open book, which features, on the left page, an image of an enclosed arcade, and on the right, a statuesque nude who could have walked off a Helmut Newton shoot. This mixture of image and text is part of a stated reference to André Breton’s 1928 Nadja, pages of which Hall re-photographed for a 2015 triptych in which he groups images of a hotel, black leather gloves, and a public park, together forming a loose narrative of a kinky European tryst.

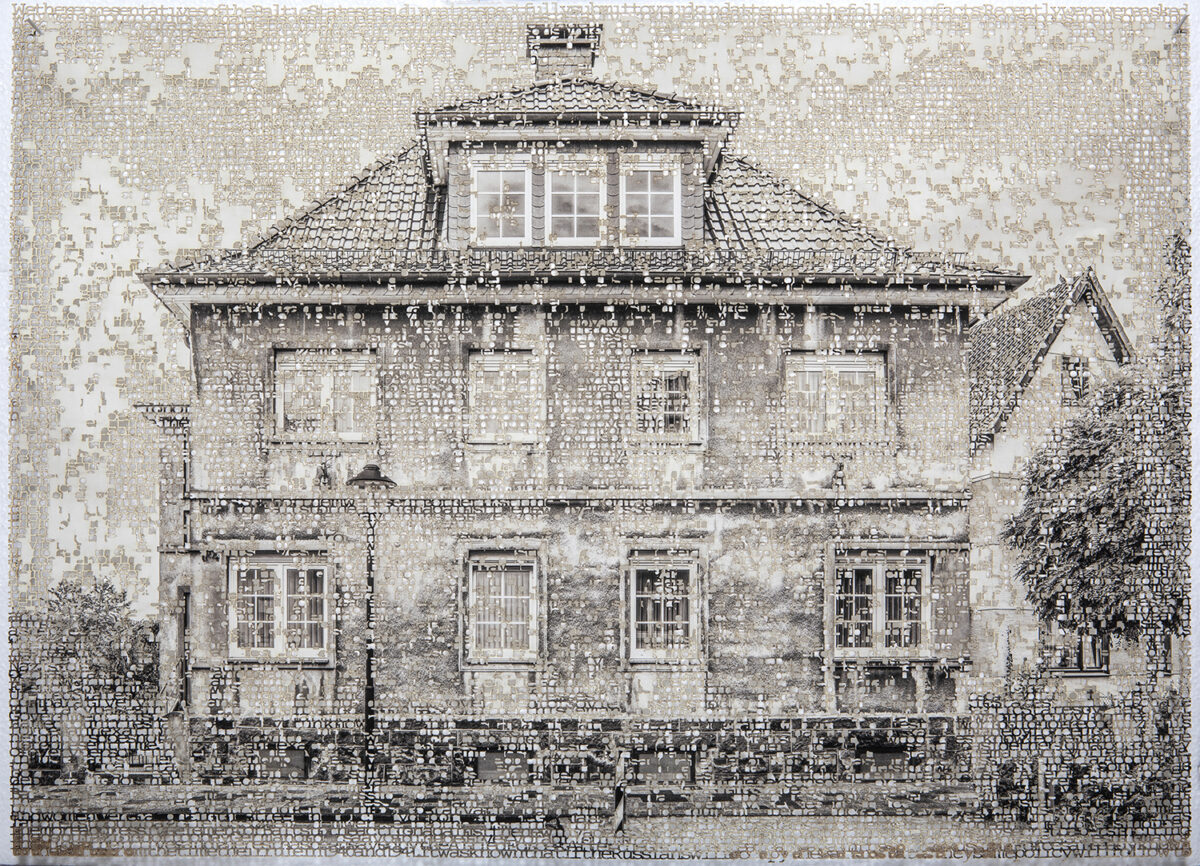

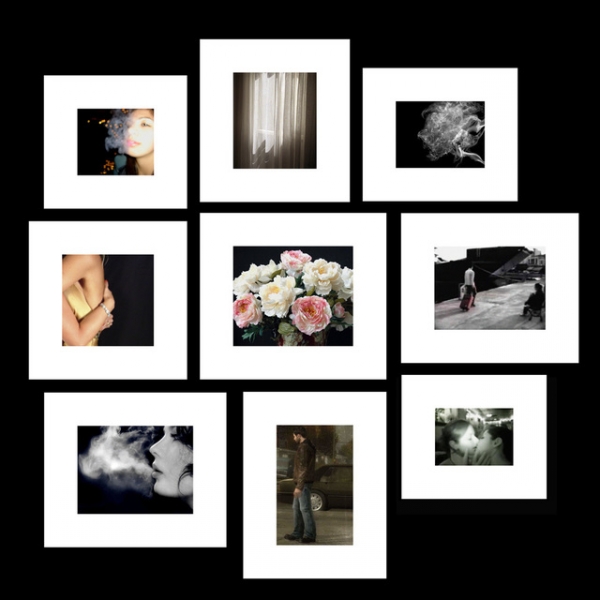

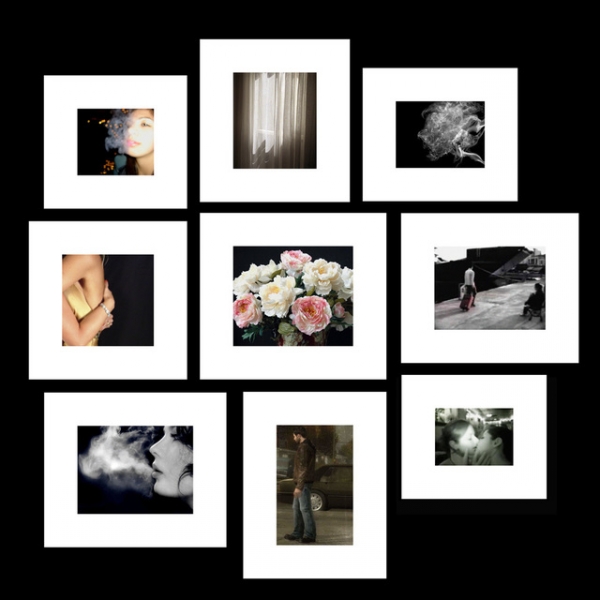

The show has an intellectual vibe, tempered with more romantic imagery. This is perhaps best expressed in And then the torpor spread like smoke, 2015, an arrangement of nine smallish images — of cigarette puffs, embracing couples, and fading flowers– sourced from the Internet, itself an insidious form of information architecture. This works fits into a contemporary art vernacular, though, while others do not– The Lonely Heart I 1989/2015, a grid of black-and-white photographs of gleaming suburban office towers and text panels featuring letters to advice columnists, feels anachronistic, an early example the artist’s dialogue with the Dusseldorf school of photographers. The gesture of tackling his archives seems promising at this point in his career, but Hall seems stymied by the gallery’s spatial restrictions. There’s just not enough room for his large themes and decades of material to coalesce.