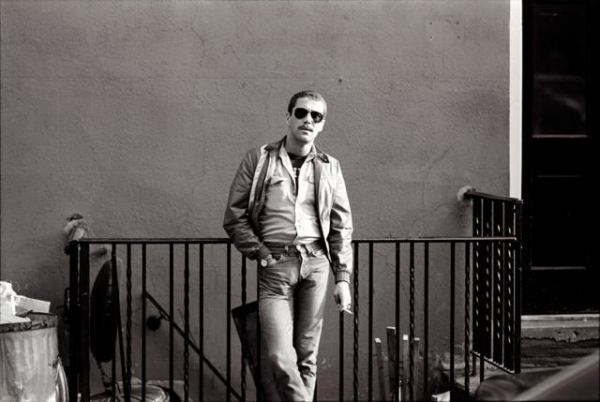

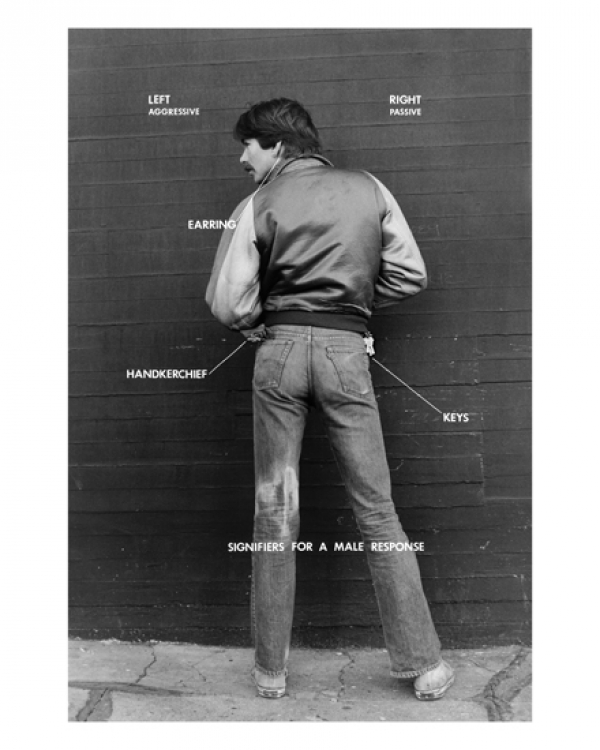

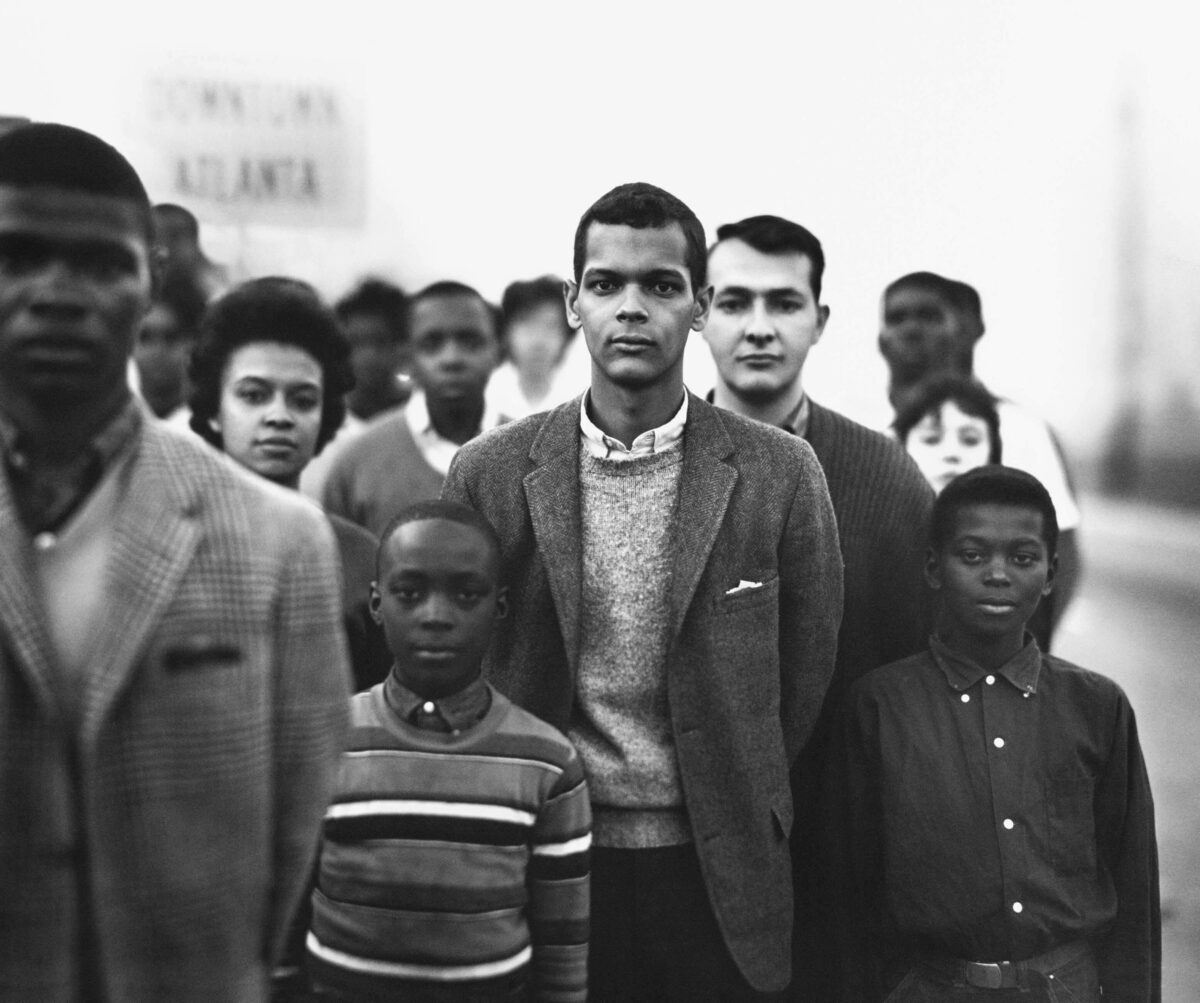

In 1969, at the age of 19, Los Angeles-based photographer Anthony Friedkin began an 18-month project photographing gay people in LA and San Francisco, approaching these communities anthropologically, as an outsider. This was a zeitgeist project, begun the year of the Stonewall riots, when images of gay life began to cross over into more general contexts. With a photojournalistic eye (the young photographer had already freelanced for Magnum), Friedkin shot and printed black-and-white images of protest, celebration, self-empowerment, and erotic moments between same-sex individuals.

The 75 gelatin-silver prints depict what now seem like stereotypical aspects of LGBT culture — activists, drag queens, Hollywood Boulevard hustlers, and all-male adult theaters. (The latter is seen in a standout photograph, Gay Cinema Interior, Hollywood, 1970, an illicit view of body parts on a movie screen as seen from behind a balding businessman.) The resulting works were envisioned as a photo essay in book form, something that has only now been realized in conjunction with this exhibition, on view at the de Young through January 11, 2015. (Friedkin’s maquette is available free in e-format:http://www.daylight.co/editions/DD1315.)

Doubtlessly, the pictures served an important social function five decades ago in creating images of a movement, and the exhibition includes vitrines holding gay and mainstream magazines that printed some of the photos in the early 1970s. Seen now, however, Friedkin’s photographs have a quaint naïvete in their youthful ambitions. “At first, I felt a bit threatened by the whole idea of exposing myself to a culture I didn’t understand,” he wrote at the time. “I came to learn that the majority of the attitudes that I had been brought up with concerning homosexuals were false, and that gay people have been one of the most suppressed, abused, misunderstood groups since the beginning of modern civilization.”

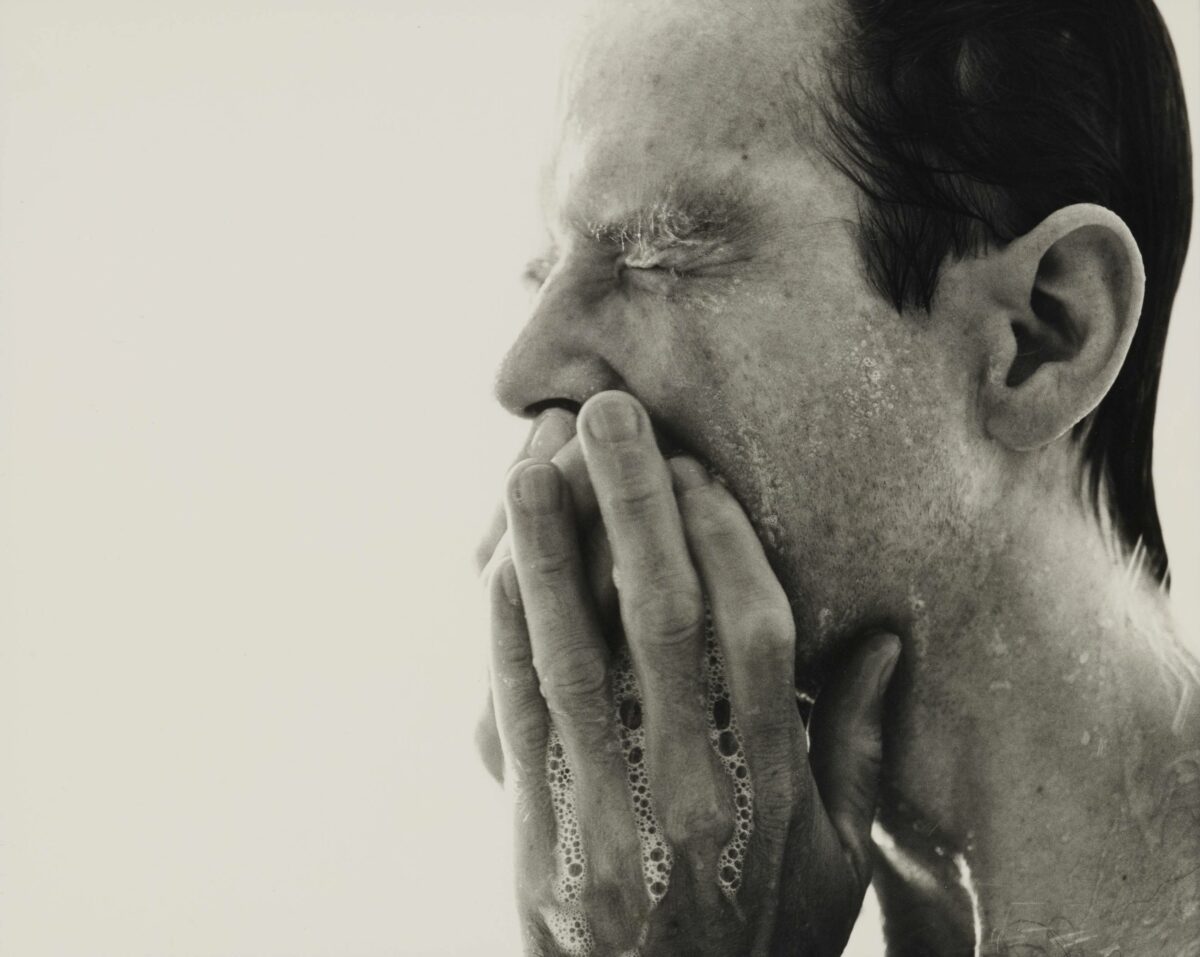

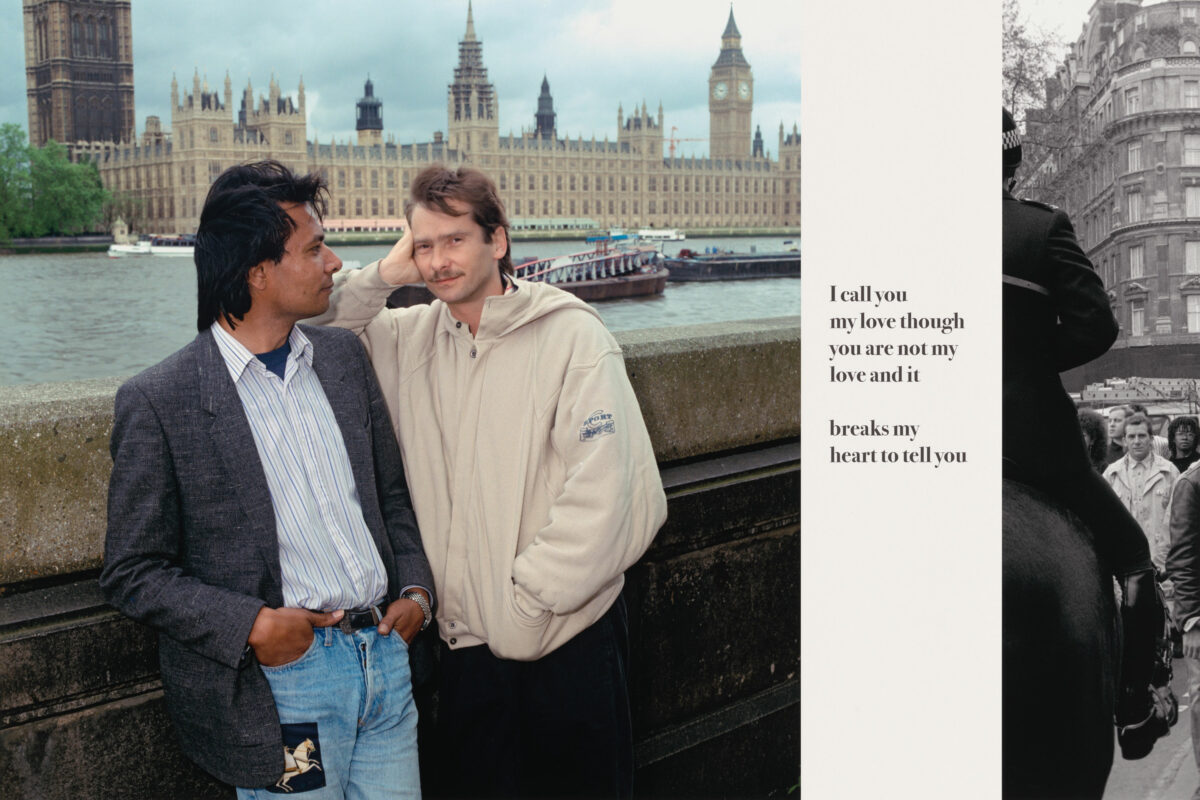

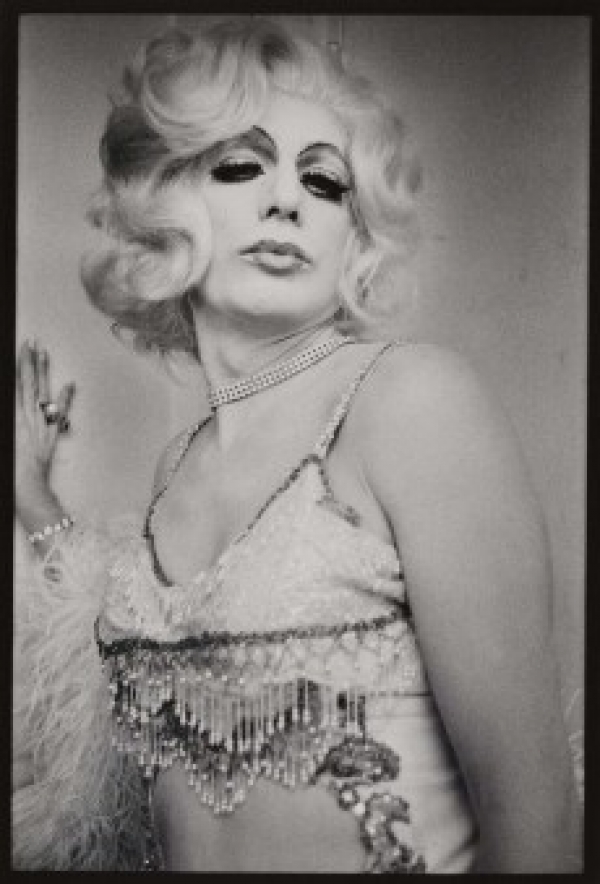

At this point in history, those civil rights lessons are harder to see in the pictures than the photographic influences: there’s a bit of Diane Arbus and Danny Lyon, and Larry Clark’s contemporaneous Tulsa work is echoed in a full frontal shot of a male prostitute. Friedkin’s eye is kinder and gentler — a burly, unconvincing cross-dresser maintains her dignity — but also a little ambivalent. In Jean Harlow, Drag Queen Ball, Long Beach, 1971, a bewigged blonde casts an indifferent glance at the camera, an impassive demeanor that precludes psychological connection.

A series of portraits of Jim Aguilar, an androgynous man from East LA who Friedkin claimed as a muse, elicits more connection and empathy. In his narrative of difference in a macho, homophobic neighborhood, Aguilar presents a more fleshed-out character than the anonymous hustlers and cross-dressers. But overall, the exhibition fails to establish Friedkin’s nascent vision, making The Gay Essay more of a historical footnote than meaningful discovery.