The Communist Manifesto was first published in London in 1848, so perhaps it is not surprising that Britain is an exceedingly class-conscious society. To this day, with a crazily anachronistic monarchy still demanding money and attention, and ever-deepening financial anxiety for the majority, Karl Marx’s observations on the uneven distribution of wealth and privilege are more relevant than ever. It is a fitting, if an unintentionally satiric, visual prequel that to enter the exhibition This is Britain: Photographs from the 1970s and 1980s (on view through June 11), one must pass through a grand foyer lined with portraits made by Jacques Louis David, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, and Francisco Goya of entitled European aristocrats in order to enter smaller galleries to view modest photographs of mostly working-class British citizens.

Encompassing photographic projects that explore the cultural changes wrought by the desperation of a post-industrial economy, including immigration, punk, gay rights, and the cultural clampdown of the Thatcher government that came to power in 1979, the exhibition features images from familiar names – Martin Parr, Chris Killip, Sunil Gupta, Paul Graham – and lesser-known photographers including Vanley Burke, Karen Knorr, and Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen. Chris Killip is surely one of the most respected photographers of his generation, and for good reason. The images in this exhibition recall the epic empathy of the WPA photographs combined with a visual grace resonant with street photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson and Josef Koudelka. By comparison, Martin Parr’s color images, which are generally understood as critical of the class system, seem like glib indulgences, suggesting the photographer’s superiority to his subjects. This smug condescension is echoed by other photographs in the exhibition, such as Hypnosis Demonstration, Cambridge University Ball (1989), by Chris Steele-Perkins, which the wall text suggests “wryly comments on the excesses and zombie-like conformity of upper-class British youth.”

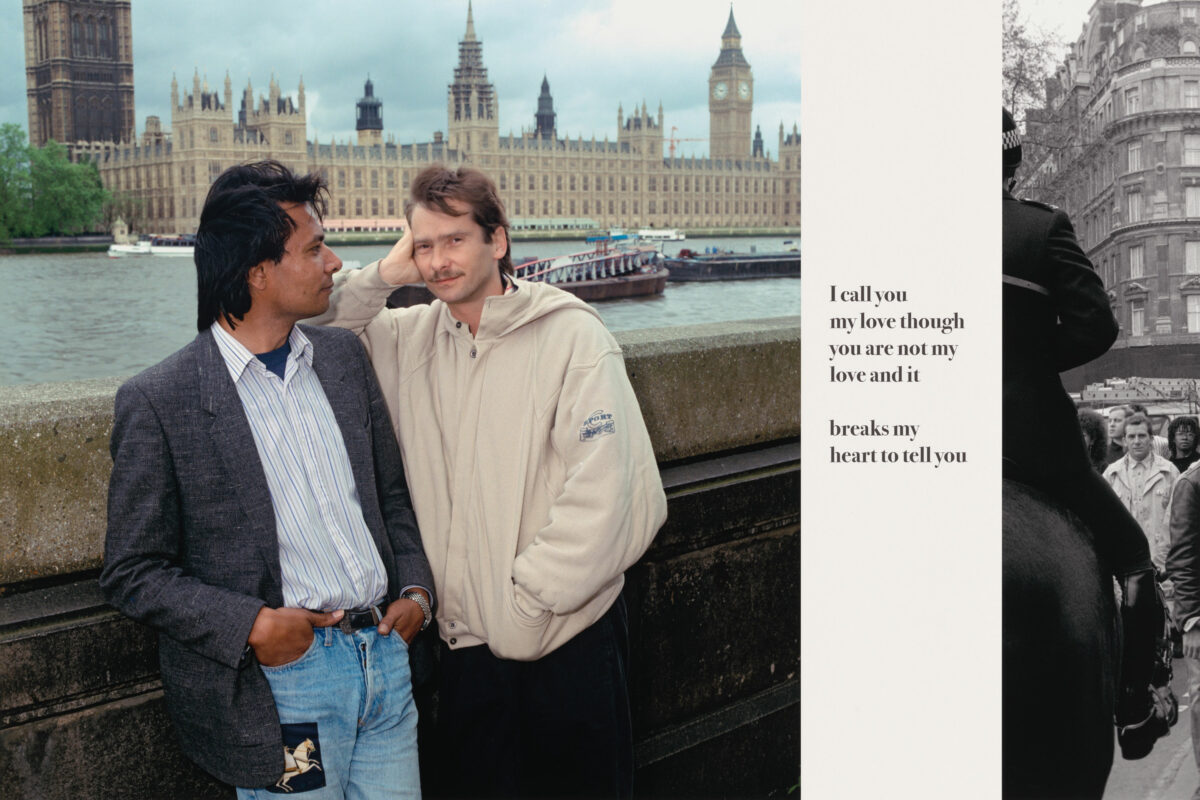

In British society, Sunil Gupta was an outsider in several respects. Born in India, raised in Canada, and self-identifying as gay from an early age, Gupta also came to photography in an era when socially conscious photography was becoming influenced by ideas from semiotics, psychoanalysis, and post-colonialism. Gupta’s ‘Pretended’ Family Relationships (1988), of large photo / text color images, was created in response to legislation against “the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship.” Politically astute, theatrical, yet also tender, Gupta’s series is a vivid example of how, in the 1970s and 1980s, artist / photographers influenced by critics / theorists such as John Tagg, Hal Foster, Victor Burgin, Martha Rosler, and others sought to complicate and implicate photography in relation to the use and abuse of representation.

Vanley Burke’s photograph Boy with Flag, from 1970, is a symbol of Britain’s post-colonial changing demographics. In this simple, sweet, and declarative image, the young man has disembarked from his bike to look towards the photographer. He appears relaxed and self-assured (perhaps because Burke himself is Jamaican), while the British flag fixed to the bike’s handlebars waves in the breeze as if to say, “This is Britain now.” An unfortunate omission in this abridged overview of socially conscious British photography is the work of Jo Spence. Spence was a feminist and socialist with an intense commitment to working-class issues. She began her photographic career as a wedding photographer in the late 1960s but after studying semiotics with Victor Burgin, Spence became a pioneering photographic artist, curator, and writer, whose work investigated class, gender roles, domesticity, and health. Her imagery, while in some ways more performative than many of the documentary images in this exhibition, was nonetheless, an urgent influence during these decades of contentious cultural change.