Heji Shin has never hesitated to shock viewers with her work. Indeed, she’s built a career on it, from her 2017 campaign for the fashion label Eckhaus Latta of real couples photographed mid-coitus to her 2018 series Men Photographing Men, in which men dressed as cops were photographed, well, fucking again (though there was more to the series) to Baby (2016). That series, which launched her into public consciousness, was comprised of images of newborns as they emerged from their mothers’ vaginas. This is not to say Shin’s use of shock is empty (though it can be) — indeed, Baby is a good example of her more humanistic aspirations. If the content is shocking, well, that’s on us.

Often, she approaches her provocative subject matter with a wink. This was the case with Big Cocks (2020), a relatively anodyne and uninspired series of photographs of roosters, and it is the case as well with the much stronger series THE BIG NUDES (2023), which were on view 52 Walker.

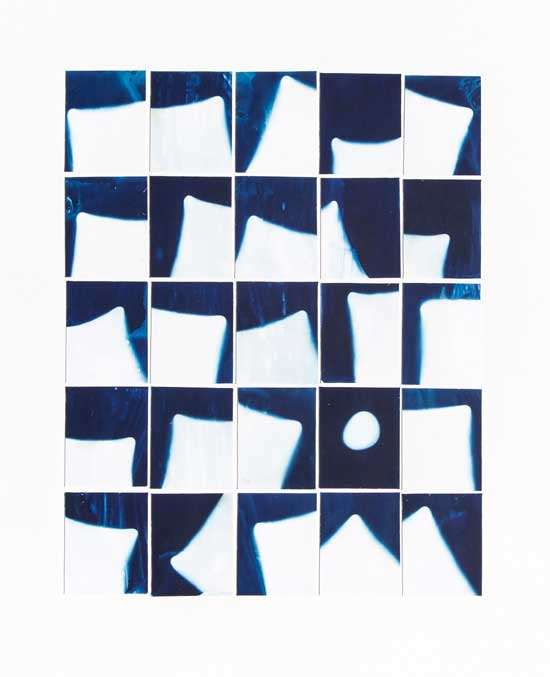

The exhibition contained two distinct and ostensibly interrelated bodies of work: images of Shin’s own brain scans, which in this context recall contact sheets, and large portraits of pigs in both color and black and white.

The series takes its title from Helmut Newton’s body of work of the same name, but the reference amounts to a somewhat empty gesture. Certainly there is an equivalence suggested between the pigs, in their humanoid fleshiness, with their humanoid eyes and expressions and poses, and Newton’s models. But whereas Newton’s photographs emphasized elements of aggression and power in female sexuality (or, rather, in male fantasies of female sexuality), Shin’s images are full of joy.

In Matt and Chris (2023), for instance, a pig lies lazily on the ground, while another pig stands behind and rests his head on the reclining pig’s rump. They are the picture of softness and tenderness. Shin’s photographs, particularly those in color, emphasize the flesh of the pigs – folds, hairs (here highlighted in high definition, appearing like windswept grass), textures – and thus gives her subjects an uneasy sensuality. The pigs’ gazes – both just off camera – suggest indifference as well as a slightly annoyed discomfort. We are beautiful and we are resting, they seem to say, leave us be.

But that’s anthropomorphism, isn’t it? Enter the brain scans, which, in their juxtaposition to the pig portraits, seem to suggest a shared consciousness, the same brain activity elevating the pigs into a status worthy of moral consideration – an elevation that occurs as a result of the implicit analogy between pig and human consciousness.

But even without the brain scans, which appear as holograms in a glass pyramid at the center of the gallery and as large prints, we know that pigs are intelligent, social beings. We can either regard the portraits of them as photographs of objects, things without subjective experience, or as portraits that speak, in some sense, about the sitter. Shin clearly intends the latter, which is unavoidable in any case when we gaze at these images.

But this comes with its own set of problems. What kinds of things can we know about a pig’s inner life? What, to borrow from Thomas Nagel, is it like to be a pig? As Nagel famously argued in What Is it Like to be a Bat?, other consciousnesses, including animals, exist in a state of unbridgeable otherness. We can know certain things about them, but we cannot possibly imagine what it is like to be a pig, because such a thought would require us to radically, and impossibly, think outside of our own embodied subjectivity.

Looking at Butch (2023), it seems clear that Shin wants us to analogize between the pig – its front legs perched playfully on a wooden box, revealing its underbelly and giving the camera a sassy sideways look – and Newton’s models, to see in this analogy the humanity of the pig. But, in fact, the image accomplishes more, enabling us to see the pig not through an anthropomorphizing lens, but as an animal, a radical other. The look then is not sassy or coy, but something indescribable because it is not readily comprehensible on human terms.

And this is enough. This is the power of the image, and the power of the Other. At the very least, as Emmanuel Levinas writes in Totality and Infinity, “the very infinitude of the other person that we see in his face is, effectively, ‘the first word: you shall not commit murder.’” This means the embrace of animals as full subjects, with all the ethics that entails. While I do not think Shin herself makes any such demand, the images, in all their force, do.