Grace Wales Bonner’s Spirit Movers, her Artist’s Choice exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (through April 7), is the most elegantly restrained of the many shows the museum has mounted in this often revelatory from-the-collection series. With fewer than 40 objects and an expansive musical theme, the show is an oasis of calm within the bustling museum and all the more stimulating for its subtlety. A London-born and -based fashion designer with a cult following, Wales Bonner has acknowledged inspiration from Black and African artists, writers, and filmmakers, both historical and contemporary. But the precise edit she draws upon for her MoMA show is not defined by race. Included in the mix of painting, sculpture, drawing, and photography are works by Jean Arp, Lucas Samaras, David Hammons, Agnes Martin, Terry Adkins, Man Ray, Betye Saar, and Bill Traylor. A similar range defines the book that accompanies (but does not catalogue) the show. Titled Dream in the Rhythm (MoMA), it also draws on the museum’s permanent collection, but it has far more photographs than the exhibition, as well as a number of texts, mostly poetry, by Nikki Giovanni, Langston Hughes, Amiri Baraka, Ishmael Reed, and others.

Wales Bonner calls the book an “archive of soulful expression,” and if not all the photographers involved (including Edward Steichen, Helen Levitt, and Lee Friedlander) are Black, their subjects are. One of the pleasures of the Artist’s Choice series is the chance to delve deeper into MoMA’s collection under the sharp eye of the curator in charge. Wales Bonner extends that pleasure with her book, bringing work by artists both celebrated and little known out of storage. Louis Draper, Roy De Carava, Jeffrey Henson Scales, Dawoud Bey, Ming Smith, Beauford Smith – all look especially fine here, often with images that fix on the endlessly expressive common ground of music and style. Even if the soundtrack is only implied, you can’t get it out of your head.

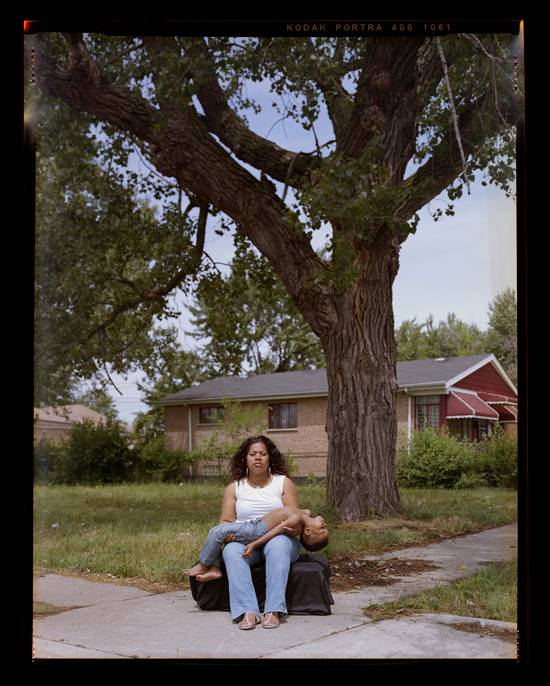

Henry Horenstein, according to his biographical note, has published more than 30 books, including a good number of photography manuals and how-to guides and others on horse racing, country-music performers, and aquatic animals in the zoo. I can’t say I paid any of them much attention, but now I’m wondering what I might have missed. Horenstein’s new book, We Sort of People (Kehrer), with a text based on interviews by Leslie Tucker, is fascinating. Its subject is a small, chatty clan of people in the Maryland hinterlands who have avoided being pigeon-holed by race. Tucker, a Black writer with a history in broadcast journalism, says they’ve “defied classification” for several generations, starting in “slavery times.” We Sort of People’s text has been edited down from 45 hours of conversations with two of the family’s oldest surviving matriarchs, Lonie and Cinderella, both of whom died in 2008. Since Lonie was also Tucker’s great-aunt, the author had already done some research on the family when she started her interviews, and she can prompt some faltering memories. But mostly she’s happy to let what she calls a “choral history” ramble on. In an early conversation, Lonie describes herself as “the lightest one in the whole family,” easily passing for white until she tanned in the summer. She names the rest of her “lighter” or “darker” brothers and sisters but says skin color was never an issue within the family: “I don’t never remember hearing no complaint or calling one another no names.”

Much of the talk is gossip of the soap-opera sort (“Mama became his stepmother when she could have been his wife”) and the larger subject of race is left to the reader to puzzle out. Horenstein’s black-and-white photographs are of friendly, ordinary people, most of whom appear to be of mixed race but who prefer to call themselves, collectively, Wesorts. Horenstein remains neutral, which sometimes leaves his pictures bland, like the society pages in small-town newspapers. But he’s excellent at landscape and atmosphere, and here and there he reminds us of Alec Soth or Judith Joy Ross. He’s got himself a great project. Just when you think it’s eluding him, he snaps it back into sharp focus.

From Walker Evans to Bruce Davidson, the New York subway system has been a stalking ground for photographers hoping to catch their fellow travelers off guard. Alen MacWeeney, an Irish photographer now based in New York, went underground when the system was at its grittiest and came back with the work in New York Subways 1977 (published “in collaboration with” the New York Public Library, where an exhibition is on view through January 6). Those of us who rode the subways in the ‘70s have no desire to go back to those grim, graffiti-covered trains and haunted stations, but MacWeeney is an excellent guide, concerned and alert. His portraits, nearly always of people who are unaware of him, ground the book in New York’s melting-pot humanity. The cars, the stairwells, the tile-lined corridors – all shot in stark black and white – could be sets for a slasher film. Printed as diptychs in an extra-wide format, the work has a tabloid kick – more sympathetic than sensational but still plenty cold-blooded.