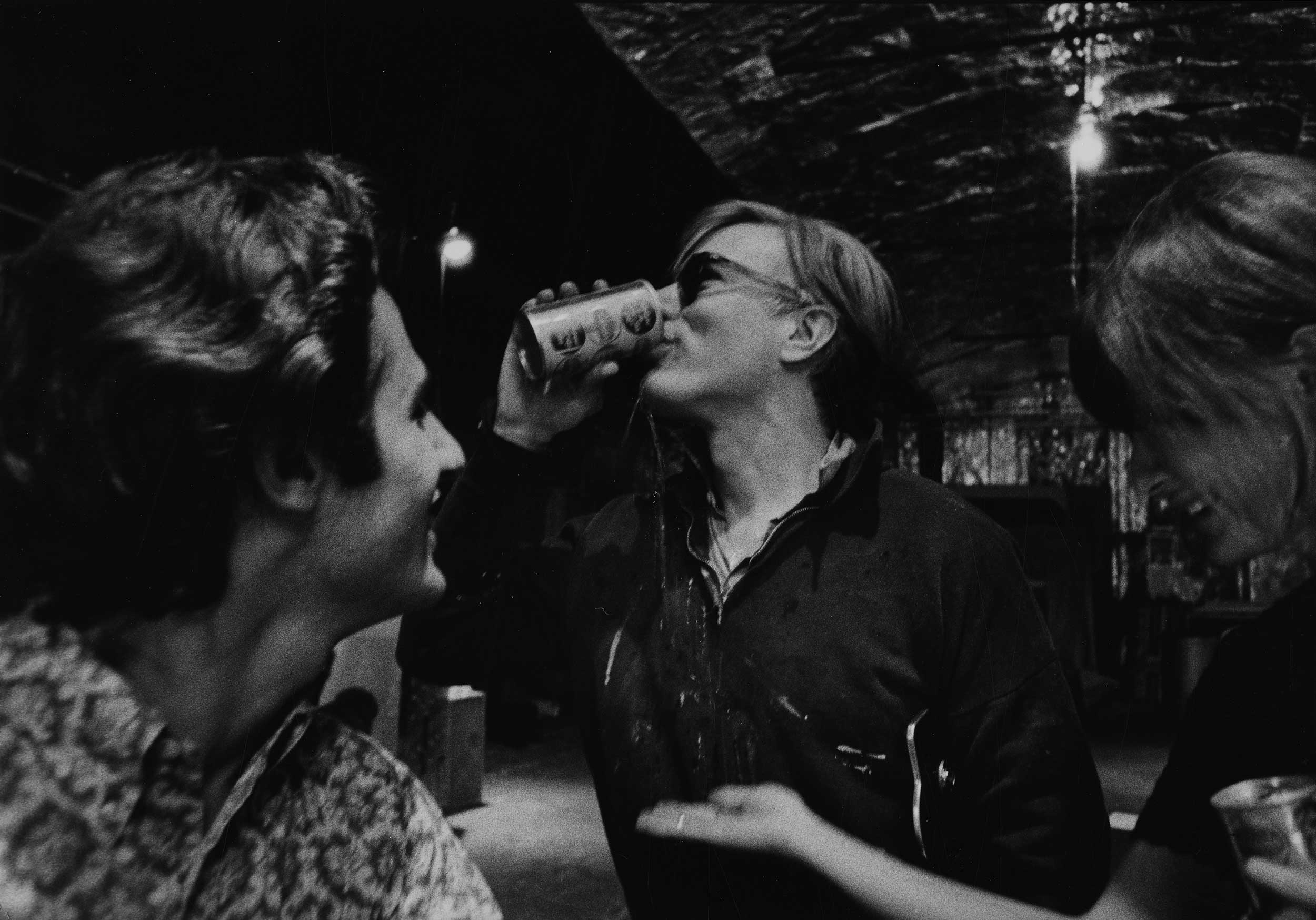

This exhibition of photographs by the Italian Ugo Mulas (1928-1973) was redolent with a double nostalgia. The first was the subject – the New York art world in the 1960s and the artists who made it the culture capital of the known universe. During three visits to New York, Mulas and his camera got inside the studios, dinner parties, and happenings of the likes of Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Barnett Newman, and Andy Warhol, among others. He charted the movement from one generation to the next, from the Abstract Expressionist legacy of “go big or go home,” in a portrait of Newman in front of a vast empty white canvas, to the casual disorder of manufacture in Warhol’s “factory,” with Jackie Os scattered on the floor. The appearance of such figures as choreographer Trisha Brown notwithstanding, Mulas’s New York is a boys’ club, no matter which way they might swing sexually. But looking at these photographs, you almost wanted to have been there.

Which leads to the second form of nostalgia: for black-and-white film. The ‘60s were anything but black and white, except in the little window of the documentary photographer’s camera. The contact sheets were here, in all their sprocket-edged geekiness. There’s Jasper Johns kissing up to a canvas, in an extended sequence of a dozen frames, and you are there, listening to Mulas click away.

I can imagine that anyone not of a certain age might see these photographs as either holy relics or almost mystifying evidence of a bygone age in New York. But cutting through the nostalgia is an experimental and, above all, artistic sensibility that used the camera to explore how artists engage their media and how the camera engages its subjects. Take that Johns series. It’s actually part of a much more extended sequence in which Mulas attempts to reveal the process of creation, even as he provokes a tongue-in-cheek performance from the artist. The gaps between the images come to represent moments of suspension, of thought or hesitation, a means of bestowing a rhythm on production. And just as Hans Namuth, in his famous photographs of Jackson Pollock at work, was interested in method, so is Mulas. Lichtenstein actually, physically paints those pictures that look like Ben-Day dots, and Johns contemplates the surface profile of a beer-can-studded canvas. Mulas emphasizes both the intimacy of contact and the distance of self-consciousness.

A larger selection of Mulas works, pre- and post-New York, would ideally have strengthened that sense of investigation. At the time of his sudden death, Mulas had completed a series of photographs called Verifications, in which he explored aspects of the medium that took him back to the first photographs and their basic questions: what is a photograph? How does it communicate? What these pictures “verified,” above all, was that their maker was that rare thing, a deep thinker with a camera, an eye, and a mind.