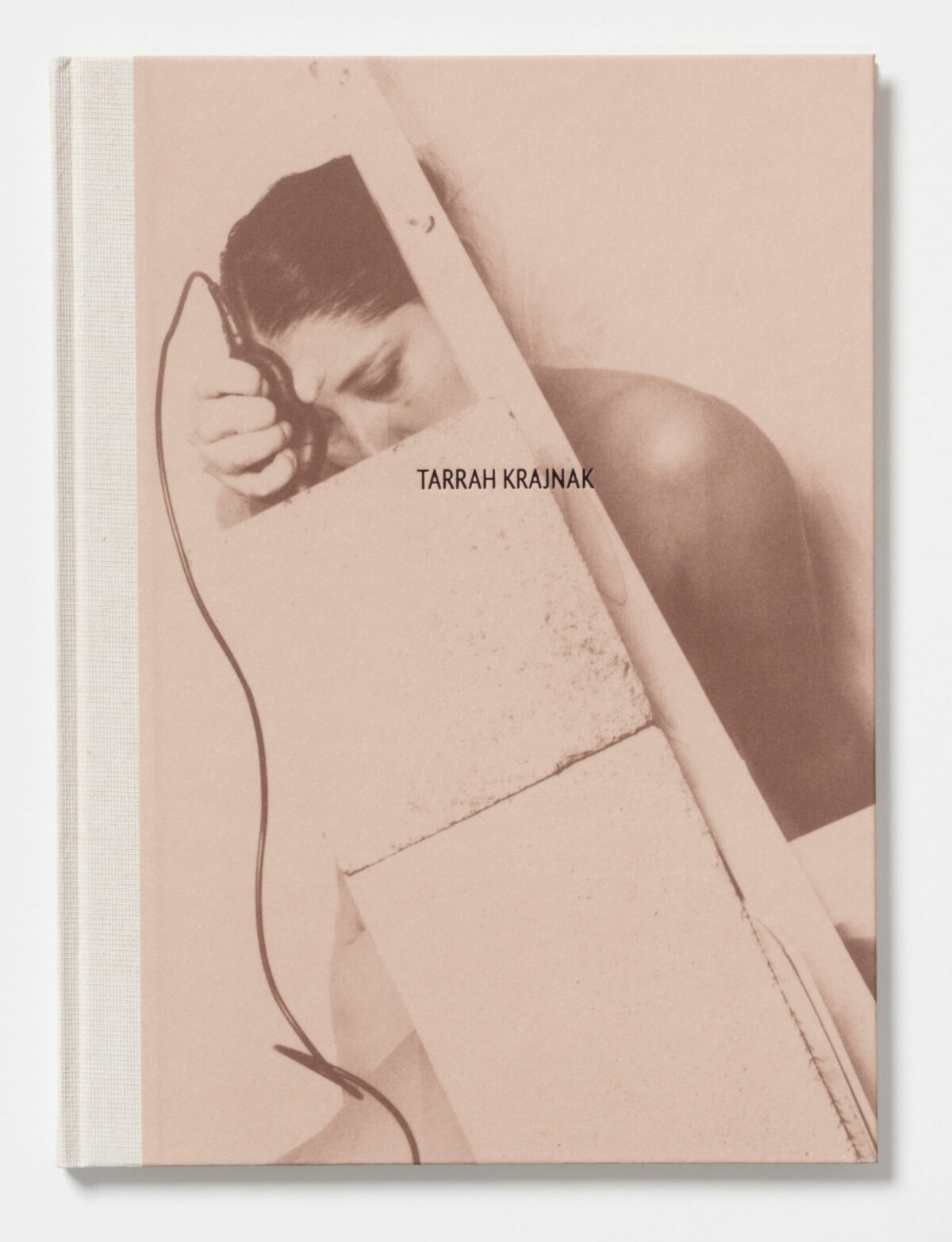

Debi Cornwall is a different kind of witness for a media age in which photography is in danger of losing its capacity to make us feel and think. She has evolved from photojournalist to civil-rights attorney to new-style documentarian and, in the process, has perfected an approach that encourages us to question everything we see. The result is on display in Lausanne, Switzerland, in an ongoing project titled Model Citizens, for which Cornwall was awarded the Prix Elysée earlier this year. The project will be published as a photo book, her third in a trilogy about the American condition, in 2024. (The first two were Welcome to Camp America, 2017, and Necessary Fictions, 2020.) Her 2021 film Pineland/Hollywood won the jury prize for Best Short at the San Francisco DocFest in 2022, and her found-footage documentary short Jade Helm, 2022, was a finalist in the mini-doc competition at the Big Sky Film Festival in Missoula, Montana.

Lyle Rexer: Your career has been interesting and oddly circular, from documentary photographer to activist lawyer, and back to photographer, albeit with a very different orientation. Can you tell me about why you made those shifts and what they mean?

Debi Cornwall: While at Brown University, I took two photography courses at RISD [Rhode Island School of Design, located next to Brown in Providence], exploring a social-documentary practice. Aside from that, I guess you could say I was self-taught in photography.

LR: Certainly self-motivated.

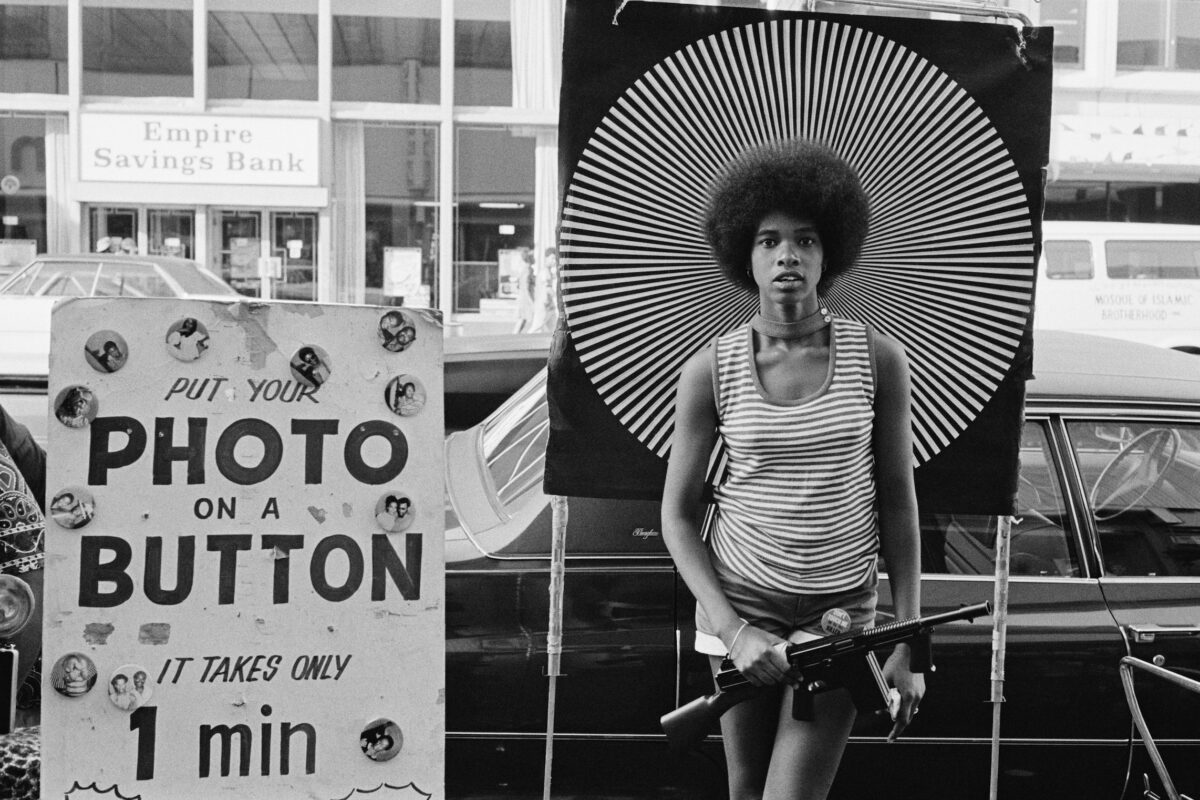

DC: I studied modern culture and media at Brown, and it was all about critically dismantling the ways images are used to advance the interests of power. During my senior year I was an AP stringer, while making classic black-and-white social-documentary images in class. I didn’t get the job I applied for as a photographer at the Providence Journal-Bulletin, however, and I didn’t know how else to be a photographer. I moved to New York and found this incredible job as an investigator for the Federal Public Defender Office, working with attorneys whose clients were accused of federal crimes and couldn’t afford their own lawyers. I only occasionally used a camera in that work, but the sense of camaraderie and meaning in that office propelled me to law school.

LR: Tell me more about that sense of meaning.

DC: Everyone I worked with was passionately dedicated to what they did. We were underfunded relative to the prosecution, which has lots of tools in their arsenal. I could see how state power could be used and abused against poor clients who tended to be people of color.

LR: Whose fundamental crime in our society is not having any money.

DC: Exactly! It felt like an important role for me. I went to law school planning to be a public defender.

LR: Did you see that the state was a problem, politically speaking?

DC: Yes. In high school I took a civil-rights class my senior year and saw the connection between the civil-rights movement, feminism, early LGBTQ activism, and how power perpetuates itself at the expense of anyone who doesn’t fit a proper profile. In law school I made the rounds of nonprofit-sector jobs to explore the breadth of public-interest work. I worked for the Southern Center for Human Rights, the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund. I went to Indonesia during the state of emergency and volunteered doing public advocacy for the return of disappeared pro-democracy activists. During a semester abroad, I volunteered as a peace monitor in South Africa. After a clerkship with federal judge Robert W. Sweet (who died in 2019) in the Southern District of New York, I joined Peter Neufeld and Barry Scheck, co-founders of the Innocence Project, and ultimately became a partner in their civil-rights law firm, where I practiced for 12 years representing DNA exonerees in wrongful-conviction lawsuits and other cases of official abuses.

LR: So the act of witnessing, looking, and monitoring – not only defending – has been important.

DC: Throughout my life, yes. When I was working on my first book, Welcome to Camp America, I met a Tunisian former Guantánamo Bay detainee who had been held for 13 years without charge or trial. He was eventually cleared and relocated to Slovakia (because, as for many others, the U.S. government decided that his home country was too volatile to resettle him there). Two weeks before I arrived, the Slovak police broke down his door and shot him with rubber bullets – apparently because, as they told him later, he had not left his apartment in three days. He survived the shooting, but he left the destruction just as it was and prepared his evidence, because he knew I was coming and wanted me to see it. To be a witness.

LR: What made you decide to move back into photography but with a very different approach from your days as an AP stringer?

DC: The short answer is, I burned out. I was working around the clock; I wasn’t sleeping. The boundary between work and life had disappeared. After a trial that had me living out of a hotel for three months straight, I negotiated a sabbatical and began traveling – Mexico, Myanmar, Vietnam, Cambodia. I began to realize that beyond the conference rooms and courtrooms, beyond cross-examining retired homicide detectives, it was a big world out there. I picked up the camera again to approach the world with curiosity rather than outrage. I was having dinner with a friend and colleague who represented Guantánamo detainees, and a lightbulb went on. I thought: I would like to photograph the men who had been cleared and released. They faced similar challenges to my exonerated former clients. That interest ultimately became Camp America.

LR: Access was difficult, and your view of the place was restricted, as it was with Necessary Fictions, about military training sites in the U.S. How did those limits influence the way you photographed, and did they have a lasting impact?

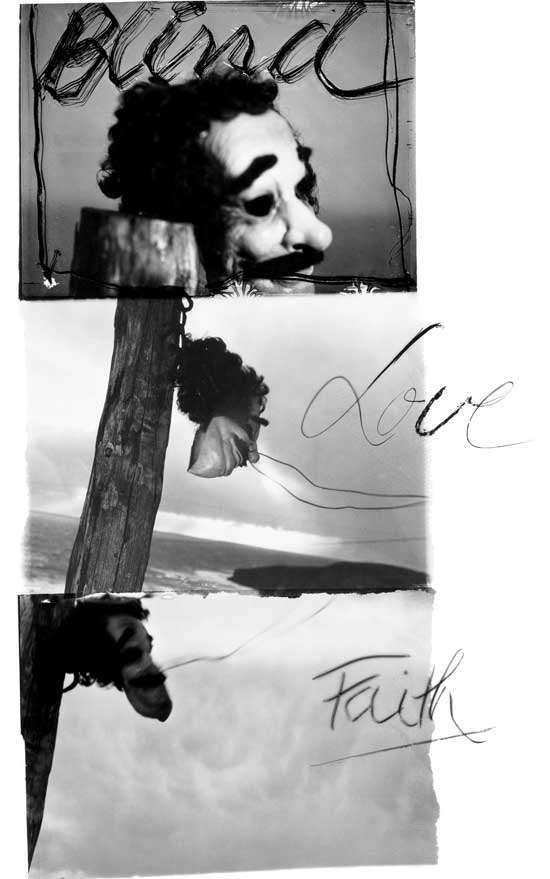

DC: In Guantánamo Bay, per military regulations, my memory card was examined at the end of each day and the images scrutinized for rule violations. Anything that, in their sole discretion, violated any of the 12 pages of rules I had signed as a condition of going – including that all faces were prohibited – would be deleted. I had one appeal, that’s it. So my visual strategy had to be oblique, finding ways to illuminate the concealed realities underlying the official media tour. My military escort told me, “Gitmo is the best posting a soldier could have!” So I went with that, photographing residential and leisure spaces of both inmates and guards, as well as gift-shop souvenirs. Then I traveled to nine countries to make environmental portraits with 14 men who had been cleared and released from Guantánamo Bay, posed to obscure their identities, as though they were still held and subject to the military’s “no faces” rule. Not showing “the thing itself” has become a foundation of my practice.

What I had learned in my media classes years earlier but hadn’t connected with my legal work until then was the arbitrariness of bureaucracy. There is always a way to appeal, but the result is just as likely to come down to who is on the other end of the phone as the justness of your argument. When I was about to begin shooting Necessary Fictions in early 2017, I suddenly received a message saying my access to U.S. Marine Corps. training locations – mock Afghan and Iraqi villages on military bases around the United States hosting immersive, realistic military war games – had been rescinded. I was told it was because I had obviously lied to get into Guantánamo Bay, years earlier, which did not make any sense to me. So I appealed, worked my way up the chain of command until I found someone in the Pentagon – a woman – who told me the real reason was a concern that I would use the project to criticize the new commander-in-chief regarding immigration. She agreed to help me, I cleaned up my Twitter account, and I was cleared to visit after all. But it was a powerful lesson.

LR: People are looking.

DC: Yes, they are, but more importantly, I had to choose what kind of artist I wanted to be. I am often asked if I see myself as an activist, and the answer is no. If I wanted to make concrete change in the world, I know how to do that, I practiced law. But working visually, I am more interested in raising questions than answering them. I am not interested in telling people what to think. I am much more interested in complexity, in subtlety. I want my work to illuminate and reframe our assumptions, to reassess what we thought we knew. Photographs are an ideal vehicle because they land differently than words do. You may be able to tune out an argument you don’t agree with, but you can’t unsee a picture. If it is crafted effectively, it won’t let you rest easy. It hits you in the gut.

LR: When you photograph in a place like Guantánamo, you have to develop a language of indirection, to suggest what can’t be shown directly. I see that working in all your photographs.

DC: That is exactly how I photograph. In a fundamental way, I am working against the strong institutional pull toward journalism. There is an infrastructure, master classes, and grants all pushing a photographer in the direction of the photo essay form, with its feedback loops of empathy. With much of that work there is no invitation to think or engage, nothing for you as a viewer to do. You feel bad for the subjects, you feel good for having noticed, you move on. I’m more interested in jolting viewers out of those patterns.

LR: As part of that aiming for the gut, your images are formally startling. Many of your choices regarding composition and color are not obviously about conveying information but about beauty and surprise. You’re going to get the hard stuff, the moral message or the knowledge, but the image will lead you there with the sweet stuff, the eye candy.

DC: My photographs invite you to look, and to question what you’re seeing as well as to consider what is outside the frame. We are exhausted by a news cycle of dire, doom-filled news and disposable, unreflective images. I have made a conscious choice to prioritize aesthetic values – as well as the unexpected, the uncanny, and the absurd – as a way to trigger a reaction in the body and the mind of a viewer, to invite new ways of thinking about what we think we know.