Like so many Black South Africans, Ernest Cole had already been evicted and relocated as a child with his family by government decree, but when he left the country and settled in New York in 1966, he knew there was no going back. He’d been working as one of Africa’s first Black freelance photographers, often for Drum magazine and occasionally for the New York Times, documenting life under Apartheid for people the system did its best to make invisible and dispensable. Even before he compiled the negatives he smuggled out of South Africa into House of Bondage, a bombshell of a book published by Random House in 1967 (and reissued by Aperture in 2022), he’d become a “banned person” back home. Inevitably, his book was banned there as well. Still in his twenties, Cole continued to take photographs in New York and eventually made his way across the country. But America proved a bitter disappointment. In 1968, he wrote to a friend that instead of the hopefulness and joy he’d expected to find and document, he felt condemned to “a lifetime of being the chronicler of misery and injustice and callousness.”

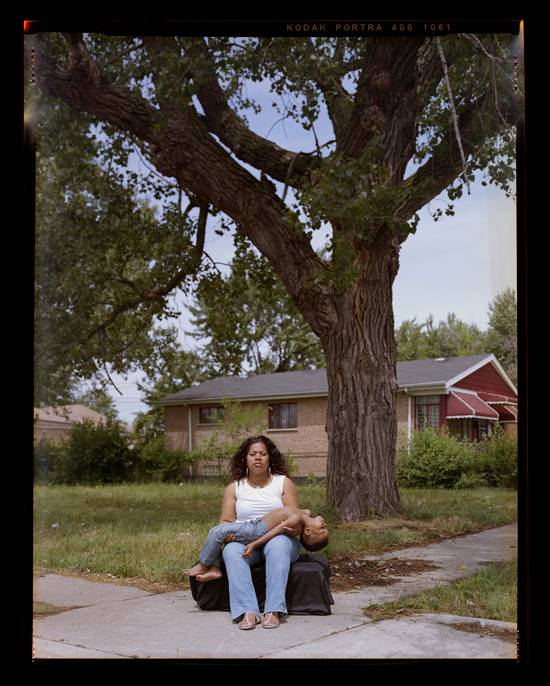

Very little of this work was published in Cole’s lifetime. He died, after a period of mental illness and homelessness, in 1990, of cancer, at 49. Much of his work was presumed lost. But in 2017, several safe-deposit boxes and some 69,000 negatives were discovered in Sweden, where he’d moved for a period in the early 1970s. That material has now been mined for a new book, The True America (Aperture), which attempts to give some shape to Cole’s work. If he found misery, injustice, and callousness on his travels across America, there’s very little evidence of that in this book. Made between 1967 and 1972, but printed here without captions or dates, the work is more up- than downbeat. Cole’s subjects are nearly always found on the street and typically snapped in passing. Most of the people Cole pays close attention to are Black and, perhaps because he was a handsome young Black man, they usually welcome his gaze; they relax, they open up. Throughout the book, Black people are present in a way that they rarely are in similarly spontaneous circumstances with Garry Winogrand or Joel Meyerowitz. So the work is immensely appealing but more casually reportorial (Cole did work through Magnum) than hard-nosed and incisive. Still, he’s a fine observer and covers a lot of ground, from Harlem shop windows (one featuring copies of Jive and Bronze Thrills) to Stokely Carmichael speaking at a Black Panthers podium in L.A. For every protest demonstration, there are ten pictures of people dancing in the street. Inevitably, perhaps, Cole anticipates Gordon Parks, but the photographer he has most in common with is Jamel Shabazz, whose work echoes Cole’s focus on Black style in all its audacity and wit, especially evident in the color work here.

The 1972 publication of Daido Moriyama’s Farewell Photography (aka Bye, Bye Photography Dear) was a turning point not just for Japanese photography but for its impact on the wider world. A hectic, seemingly random collection of grainy, over-inked, and oddly cropped images (Moriyama called it “a mad dash of impulses and ideas”), it remains one of the most radical photography books of the last century. Apparently, it knocked Moriyama for a loop. He remained blocked for more than a decade until he was interviewed for a new magazine, Shashin Jidai (Photography Age) and asked, by the way, to contribute to its launch issue in July 1981. Hesitant at first, then caught up in the momentum of a new project, he contributed regularly until it ceased publication in 1988. As the title suggests, Daido Moriyama Shashin Jidai 1981-1988, a handsome new book published by Dashwood, our favorite New York photo bookstore, in collaboration with Session Press, fills in this gap in his history.

Since nearly all the original prints were lost, the book reproduces everything as it appeared on the page. Some images are blown up to fill full pages; most are included in stacks next to captions in Japanese. Longer texts, most by Moriyama, are translated. His writing is straightforward and unpretentious; an essay on how he came to be involved with Shashin Jidai is terrific. The essays, like the photographs, are as engaging as diary entries: this is what I was thinking about today; this is what I saw. And the work he made for the magazine is typical of what we’ve come to expect of him now: messy, obsessive, over-exposed or thick with grain, and so random you’re constantly off guard. One sequence includes an industrial smokestack, a wine bottle, the silhouette of a man smoking, and a nude woman partly obscured by a piece of lace. Mostly, there are street scenes: Moriyama writes about setting off on foot most days, avoiding the main streets and wandering down alleys. The book has a similar trajectory, or lack of one, its pleasures involve wandering along with a great, eccentric photographer and seeing whatever caught his eye over a period of seven years. It’s not a lesson; it’s an immersion.

Cindy Sherman’s recent show is reviewed elsewhere in this issue, but I wanted to recommend its catalogue, Cindy Sherman 2023 (Hauser & Wirth), which greatly expands on the exhibition. It’s difficult not to have mixed feelings about the work – deliberately crude and digitally manipulated mash-ups of photographs of Sherman’s face that are so comically grotesque you can’t really take them too seriously. She’s not dressing up as country-club ladies or Hollywood has-beens, she’s inventing figures from scratch – or from photo-collaged shards of her own face. Still, the work is too accomplished and too unnerving to be dismissed as mere entertainment. Besides, it’s Cindy fucking Sherman. Among the best things in the catalogue are five pages of what are presented as diary entries, the first few from 2010, when she’s toying with mock-ups for collaged faces and heads. “Weird but too corny?” she asks herself before putting them aside. She picks up the idea again in 2022, when it occurs to her that “b/w renders them more fictional, closer to drawings,” and she keeps at it. “I’m not even sure I like them yet,” she writes the following year. After a whole career of pointed and outrageous self-manipulation, it’s surprising to read Sherman’s entries about “dreading being in front of [the] camera again” and how she finds it “horrible looking at myself.” Finally, though, she decides that “using face apps for my Instagram portraits has made me rethink the way I use photoshop for these images…. Helped me loosen up, be more reckless, less precious, take chances.” Besides, she adds, “No one has to see anything I don’t like.” But if she’s holding anything back, it’s hard to imagine they’re more disturbing or hilarious than what she’s delivered.