Martha Rosler is a provocative artist for politicized times. Her early video Semiotics of the Kitchen, 1975, has long established itself as a key feminist work, and her series of photo montages against the Vietnam War, made from 1967 to 1972, definitively updated a political genre. Her work since then, in many mediums, has been equally committed to political awareness. Martha Rosler: Irrespective, at the Jewish Museum through March 3, is the first survey of her work in almost 20 years.

Lyle Rexer: I am especially interested in the role of photographs in your collages, especially your well-known series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, 1967-72.

Martha Rosler: Those works may be well known now, but I kept them out of any art-world context back when they were part of an effort to stop a war. And to be accurate, these are not collages but montages – that is, they are not arbitrary or random assemblages but appropriated images that are integrated into coherent pictures, in this case political ones. I probably had the idea of working this way from childhood. Collage is one of the simplest ways of making pictures, something we are taught in grade school – pasting things together. Of course, I had other things in mind: the early Cubist works of Picasso and Braque, where they brought swatches of fabric into the frame, the Dadaists and Surrealists such as Max Ernst, and the West Coast artist Jess. At a certain point, the person most on my mind was probably John Heartfield, who made brilliant montages attacking Hitler and the Nazis. But in the 1960s, his work was little known and virtually unpublished here because of the influence of the Cold War and his Communist allegiances.

LR: I am pleased to see a younger generation of artists, especially women, discovering your montage works. The medium is making a comeback in a big way, I think because the digital revolution has put such a premium on cut-and-paste strategies.

MR: With the advent of computers, collage became clip art, elements you could use and combine at will. Combinatory strategies make a lot of sense now, and Photoshop has become naturalized into our visual world, perhaps in search of a “truer truth.”

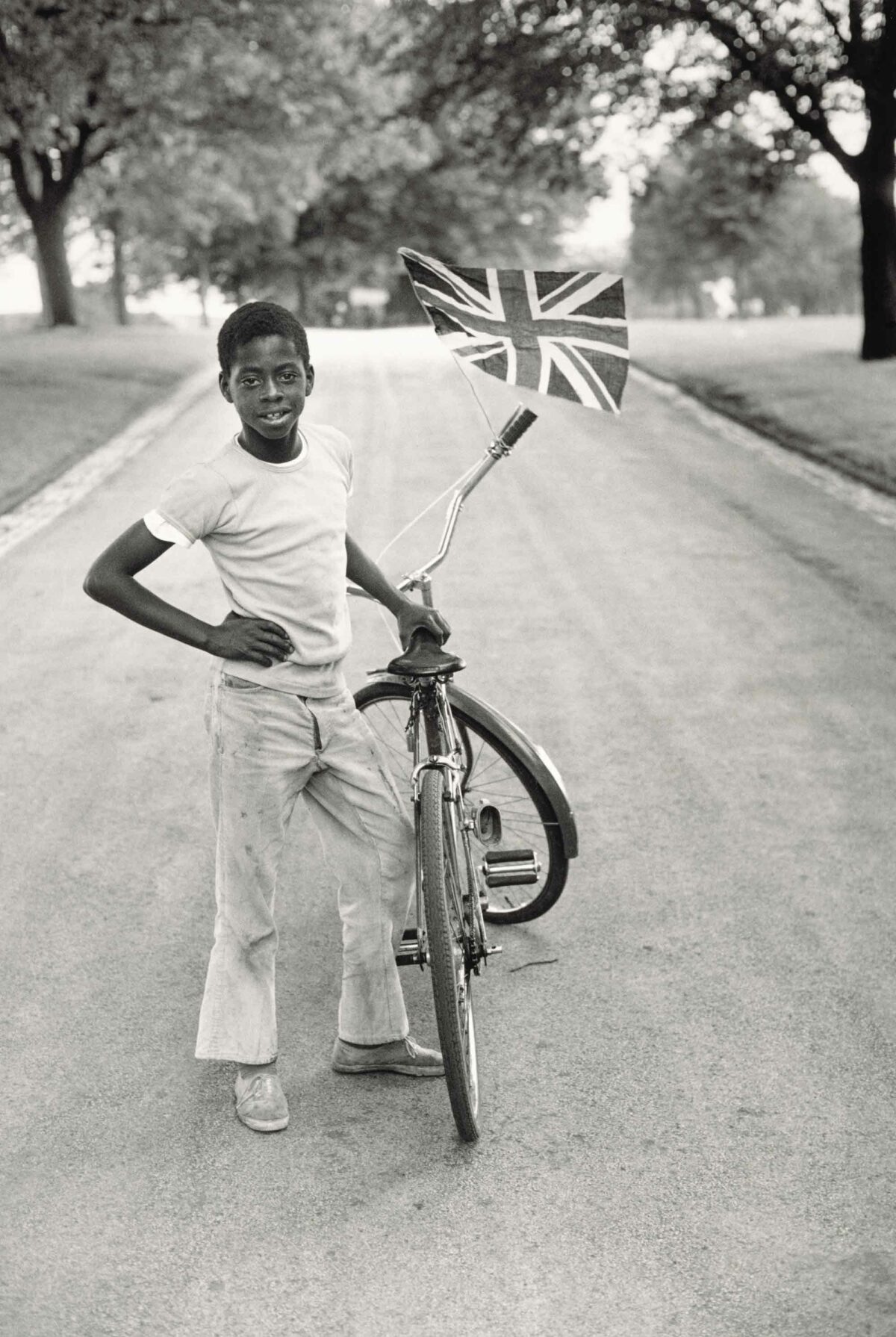

LR: Would you say that collage/montage is implicitly political? That is, it involves the deliberate decontextualization of familiar images. It breaks the habits of reading images.

MR: Yes. It’s basically media critique. And the dislocation affects not only the visual content of the images but their spatial and temporal character as well, making the critique substantive.

LR: The other thing about the antiwar series is that it looks great. The designs are clever. They work perfectly within the visual spaces of the modernist house as magazine photos represented it.

MR: Thanks! I do care about that – I mean, I was an abstract painter, for God’s sake. I pay attention to issues of form. I am not a fully casual user of photography like Dan Graham in his work on private housing, much as I deeply value his work. My work is not anti-aesthetic or deliberately de-skilled – I mention this because those words have figured as a major element of pushback against work like mine.

LR: Well then, to paraphrase the title of Richard Hamilton’s famous collage from the late 1950s, just what is it that makes photography so different, so appealing?

MR: I have a love/hate relationship with photography. When I was young, when I went on dates with guys, we would wind up stopping in front of all the photo stores while they ogled the equipment. I was both repelled by and attracted to that. I am not averse to technical interests – I majored in physics for a while, and my much-older brother was an enthusiast of then-arcane electronics when we were kids. In terms of taking photographs, though, my mother was a model for me, and my aunt gave me my first camera when I was a teenager. Making photographs is what painters do on their days off. Even as a painter, I justified my growing interest in photography because I believed that even painters, abstract painters, needed narrative in their lives.

LR: In so much of your work on view at the Jewish Museum, from early projects like The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems, 1974-75, through the Greenpoint Project, 2011, the presence of extensive text indicates almost a failure of confidence in photography, as if it could not do, in any documentary sense, what you or anyone might want it to do.

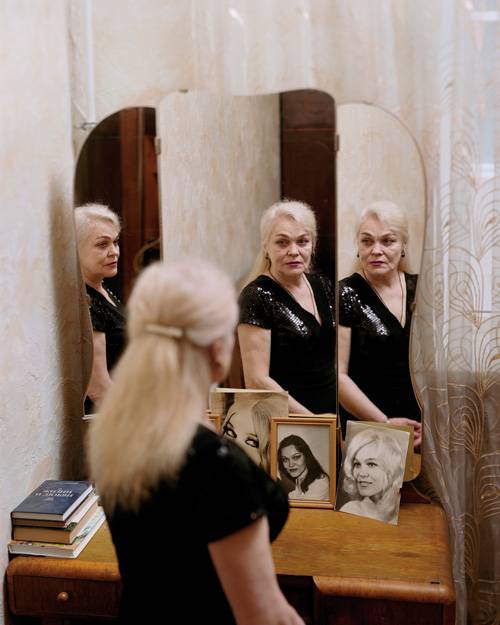

MR: You mean deliver truth or tell a story? No single photograph can do that. It is contingent. A photo contains no truth about anything, only offers the potential for suppositions. It needs a context in order to mean. We want to believe that a photograph is a window to reality, to the soul, or for lack of a better word, to God.

LR: We want to believe in its self-sufficiency.

MR: That’s why hybridity is so important to my work. With The Bowery … , for example, I wanted the presence of text to provoke people to ask about the photographs – about any photograph – what’s in the frame and what lies outside it? What is the context of the images they see? In that sense the Bowery itself was not important. You might say this was a meta-photographic work in which the Bowery functioned as an example. Sometimes other photographs can supply a context, and that context can extend over bodies of work. For example, the so far “unaccompanied” photos of the roads and subways I have shot take their meanings from the airport photographs of In the Place of the Public: Airport Series, 1990, which is interspersed with isolated phrases, and even from The Bowery, in which the texts are attached to mostly unrelated photos. My work provides a context for my work.

LR: I wanted to ask you finally about a longer-term example of street photography. You have been photographing your Greenpoint neighborhood – people and places – for decades.

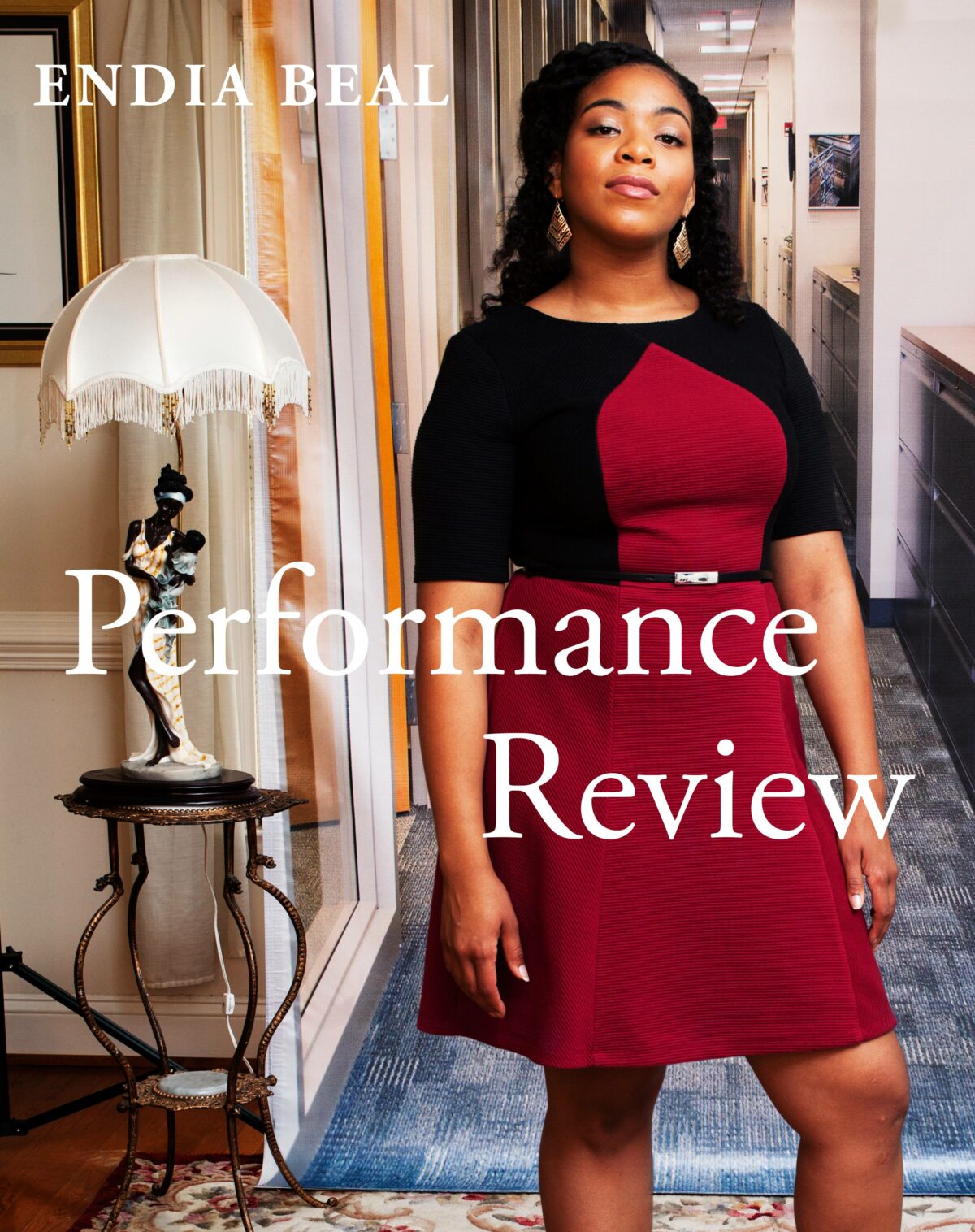

MR: It began with a desire to photograph pollution sites here in Greenpoint in the early 1990s, but more broadly I wanted to document the demographic and economic changes that were happening around me. The earliest project, in 1992, Greenpoint: Garden Spot of the World, included a video and maps, and books abut how to fight pollution. But for the most recent projects, especially Greenpoint Project, 2011, I wanted to make work that was concrete and local, so I talked to people face to face, mostly those I knew from retail encounters or because they were my neighbors, asking them about their work, and I paraphrased their stories – I don’t trust taking quotes out of context, just like photos – and I made portraits of them. The final work uses two pictures for each person, not single views. And if people refused to be photographed or even talk to me, I would include information about that, too. Look, taking and showing portraits of people, especially those in precarious positions, in an institutionalized setting like a museum can be quite unethical if not handled carefully. It appropriates and projects onto others a kind of dubious psychologism when of course people have their own reality. The representation of alterity is one of our culture’s biggest knots right now, and self-representation is often the key, providing the wider context in which photographs are viewed and narratives told.