Since her stint at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, which lasted a dozen years, Charlotte Cotton has become something of an itinerant curator, a bit nomadic, a bit promiscuous, one might say, as Cotton herself did, with a laugh: “Once I began to forge my midlife crisis, it was a decision about wanting to say something that is a strong and plausible argument for how we should look at photographs.” She has worked at the National Media Museum in Bradford, England; the Photographers Gallery in London; and LACMA, though she has curated exhibitions at many institutions. She’s also a prolific author, most recently of Photography Is Magic (Aperture), which explores the landscape of experimental and post-internet art.

And now, of course, she is the first curator-in-residence at the International Center of Photography, where she put together Public, Private, Secret, the inaugural show in the center’s new home on the Bowery, along with associate curator Pauline Vermare and assistant curator Marina Chao.

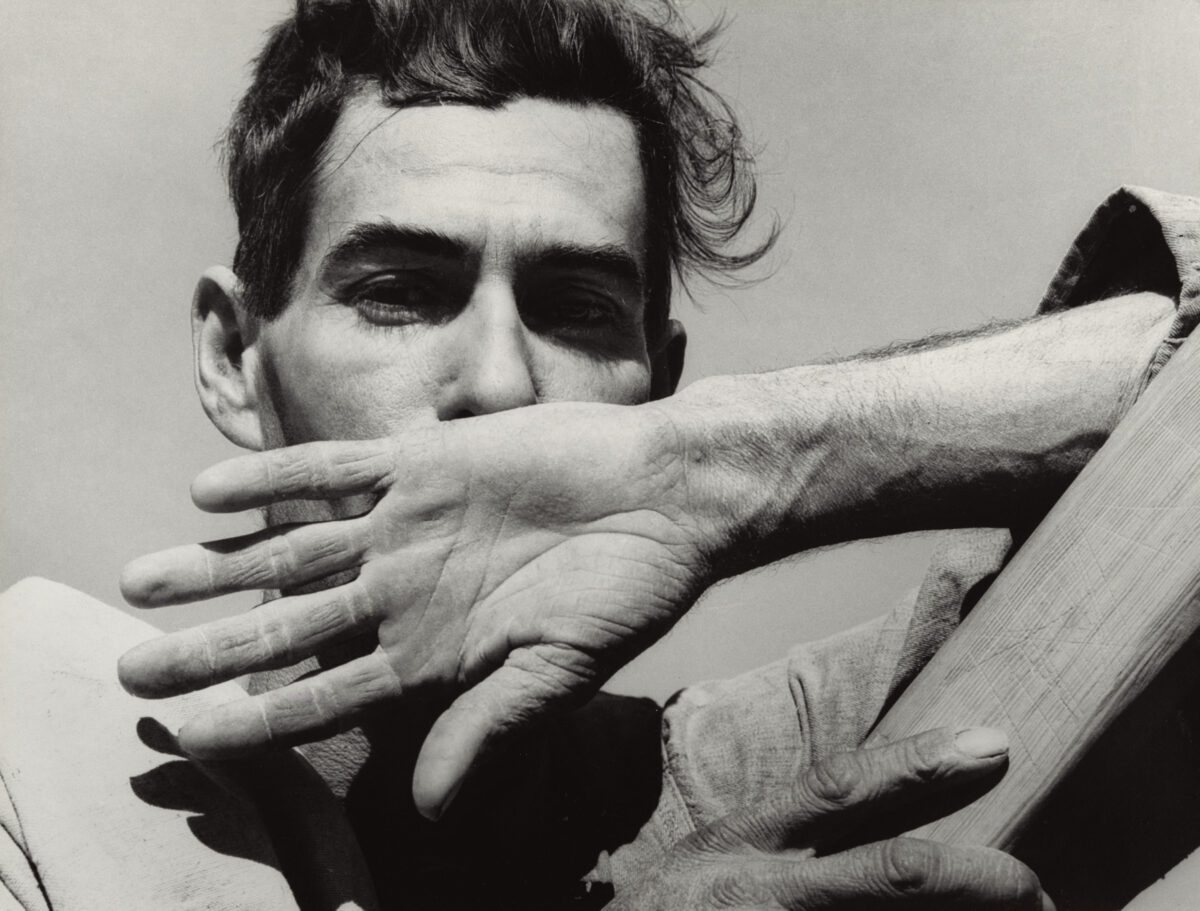

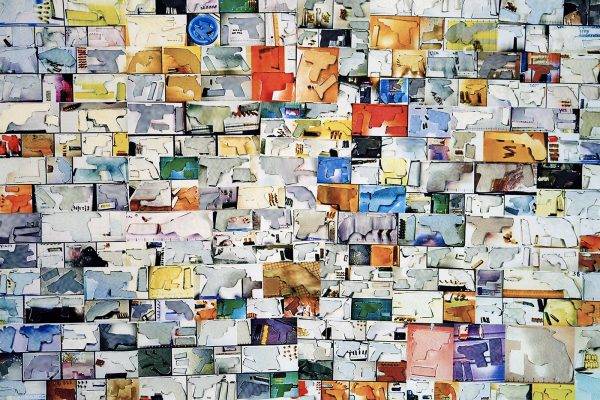

The immersive exhibition, which explores the concept of privacy in today’s social media-saturated, highly surveilled culture, includes work from over 50 artists, ranging from the “epically strange journeys through the web” of online pioneers Jon Rafman and Doug Rickard to Martha Rosler’s The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems, from 1974-75, to give some sense of the range of work. It also includes workshops on how to encrypt your emails or find out if the FBI has records on you. When I said it all sounded a bit disquieting, she conceded that she does cover the camera on her computer now, but adds, “Awareness is empowering. Hopefully it makes you say: We the people can deal with this.”

Cotton was born in the historic Cotswolds: “It was very beautiful, but I couldn’t wait to leave,” she says. Her parents were furniture restorers who wrote the first history of vernacular furniture traditions in Britain and whose collection is in London’s Geffrye Museum. They had a photography studio, to document the furniture they were researching, and when she was a teenager, Cotton began working in a darkroom herself. When she was 17, she went on a school trip to London for an economics class. “We were supposed to go to Lloyd’s of London, and I kind of skipped out on that and went to the V&A and saw an Irving Penn exhibition. Then I went to The Photographers’ Gallery to see what I should be wearing: what did it look like to be a cool artist interested in photography?”

The die was cast: after graduating from the University of Sussex, she got an internship at the V&A, where she worked for the estimable Mark Haworth-Booth, who Cotton calls “a beautiful human being.” She worked at the print room at the museum, which is open five days a week to anyone who wants access to works on paper. “I just thought: This is it, this is what public access means,” she says. “The mission was to increase the physical and intellectual access of photography, and I take that really seriously.”

Indeed, that sensibility informed her concept for the ways this exhibition unfolds: “ICP has always been dedicated to the social impact of image-making, and I see this as a space that has to welcome your thinking, rather than instruct you.”