Brooklyn born and bred, Nona Faustine has her first solo museum show, fittingly, at the Brooklyn Museum. For this exhibition, which opens March 8 and runs through July 7, the museum is focusing on her series White Shoes (2012-2021), which has been included in dozens of group exhibitions across the country over the years, including at MoMA, the Studio Museum in Harlem, and ICP, all institutions which have also acquired the work.

Visually arresting and deeply layered, the series is also important for the ways it reflects the larger national discourse around race. This has been consistently true of Faustine’s work, from her series Mitochondria (2008- ) to White Shoes and My Country (2019- ), and future survey exhibitions of her work will surely bear this out.

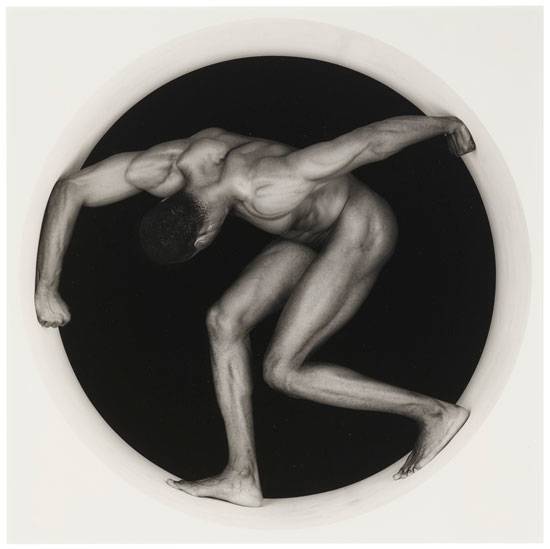

In White Shoes, which was published as a monograph by Mack Books in 2021, Faustine poses at various New York City sites in order to point to a reparative history of the City that includes the contributions of enslaved and free Africans from colonial times into the mid 19th century. In the earlier photographs in the series, Faustine is nude, her ample body a monument to the individuals whose lives she stands in for.

The titular shoes the artist wears in each image are kitten-heeled pumps, proper and low-heeled enough to wear to church, or to a job as an old-fashioned secretary or a bank teller – anywhere a woman’s appearance is expected to not draw attention or offense, but instead, to literally toe the line. They are also, of course, white, evoking the race that dictates these standards of beauty and respectability.

In these shoes, Faustine is a time-traveling goddess, summoning her ancestors in a complex embodiment that is part performance, part protest, and part spiritual communion. Her appearance in the photographs can be understood within a framework that writer Jessica Lanay, in an essay in the monograph of White Shoes, deems the “Afrofantastique,” a practice that draws on African traditions of conjuring ancestors through masquerade in order to confront political structures.

It should be said that the artist herself is not keen on characterizing her appearance in her photographs as “performance” and has stressed that it is very much herself – Nona Faustine – who appears in them. The agency she asserts here is crucial, given that the history of photography is rife with women of color who were denied subjectivity in images of them made by white men. The defiant insertion of self Faustine makes with her camera is where the power in these images resides.

Consider Over My Dead Body, Tweed Courthouse, NYC (2013), in which we see the artist from behind, wearing only her white shoes, ascending granite steps toward imposing oak doors and Corinthian columns. Her arms are at her sides, shackles dangling from her left hand, right hand clenched in a fist; the lines and curves of her flesh contrast with the grey geometry of the courthouse. The building lies above, and is surrounded by, the graves of enslaved Africans on whose backs the city’s institutions and infrastructure have been built.

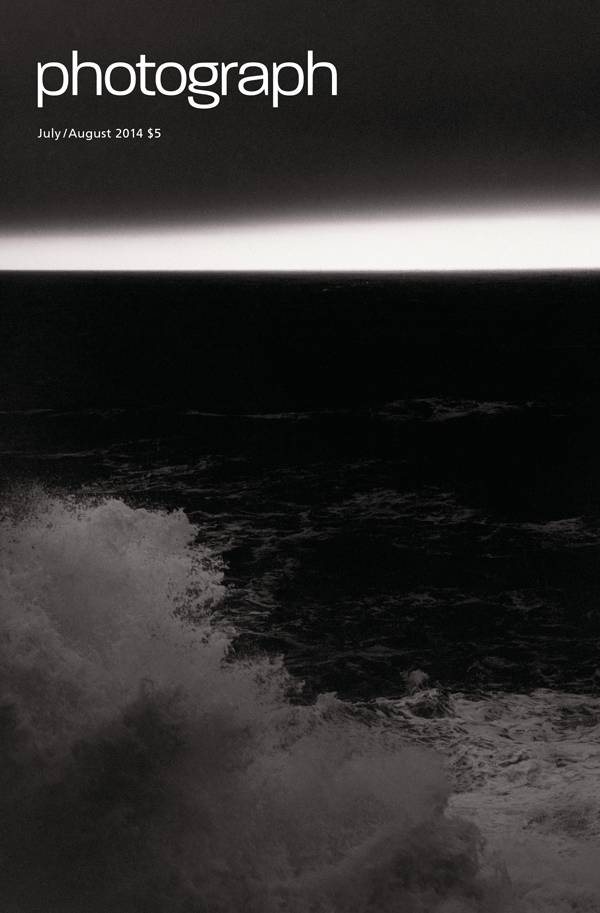

Faustine moved forward in New York’s history over the years that she created these images, and in later photographs we find her more often in a white cotton skirt with a single antebellum ruffle, topless or in a loose cotton top. In some of the more recent works, Faustine is in a pose of leisure, reflecting self-determination and pleasure, as she is in Black Indian, Andrew Williams Home Site, Seneca Village, Central Park (2021). Seneca Village was the predominantly Black community of homeowners that thrived from 1825 to 1857, after which the City took the land by eminent domain to build the park. Near the site of the first homestead, Faustine lies on her belly in her white cotton dress and sunhat, white shoes kicked up behind her, engrossed in her book about the entwined histories of native and Black Americans. The ease she reflects in this and later images evokes the ideas typified in Tricia Hersey’s recent bestseller Rest Is Resistance, about how African-American reclamation of time for rest and dreaming is a radical and generative act.

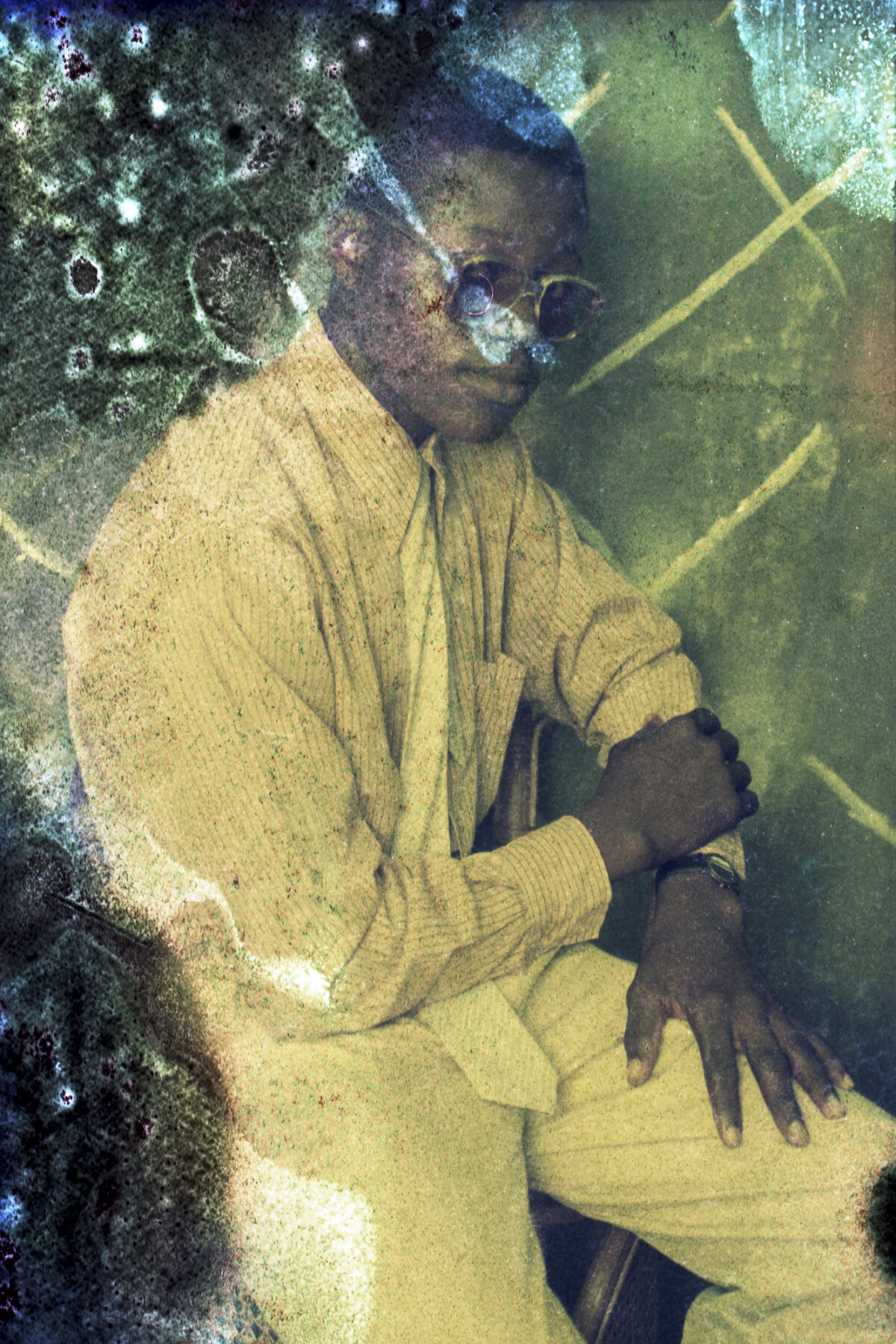

As she has walked ahead of America’s racial discourse in White Shoes, Faustine has also done so in series she began before and during its development. In Mitochondria, titled after mitochondrial DNA, which is carried solely by the maternal line, the political is personal. This series comprises photographs of the artist and her immediate family – her daughter Queen, her sister Channon, and her late mother Queen Elizabeth Simmons – who lived together in a culture-rich, interdependent, multigenerational Brooklyn home.

bell hooks, in her 1995 essay “In Our Glory,” wrote that displays of Black family photographs are a “critical intervention, a disruption of white control over black images.” Indeed it was the family albums her father assembled that sparked Faustine’s interest in photography as a child. Mitochondria is a family album of sorts, comprising both staged and candid images, one in which Faustine’s cherubic daughter is steeped in the nurturance, love, and pride of the two generations of women before her, and the continuity and resilience of Black women becomes the subject.

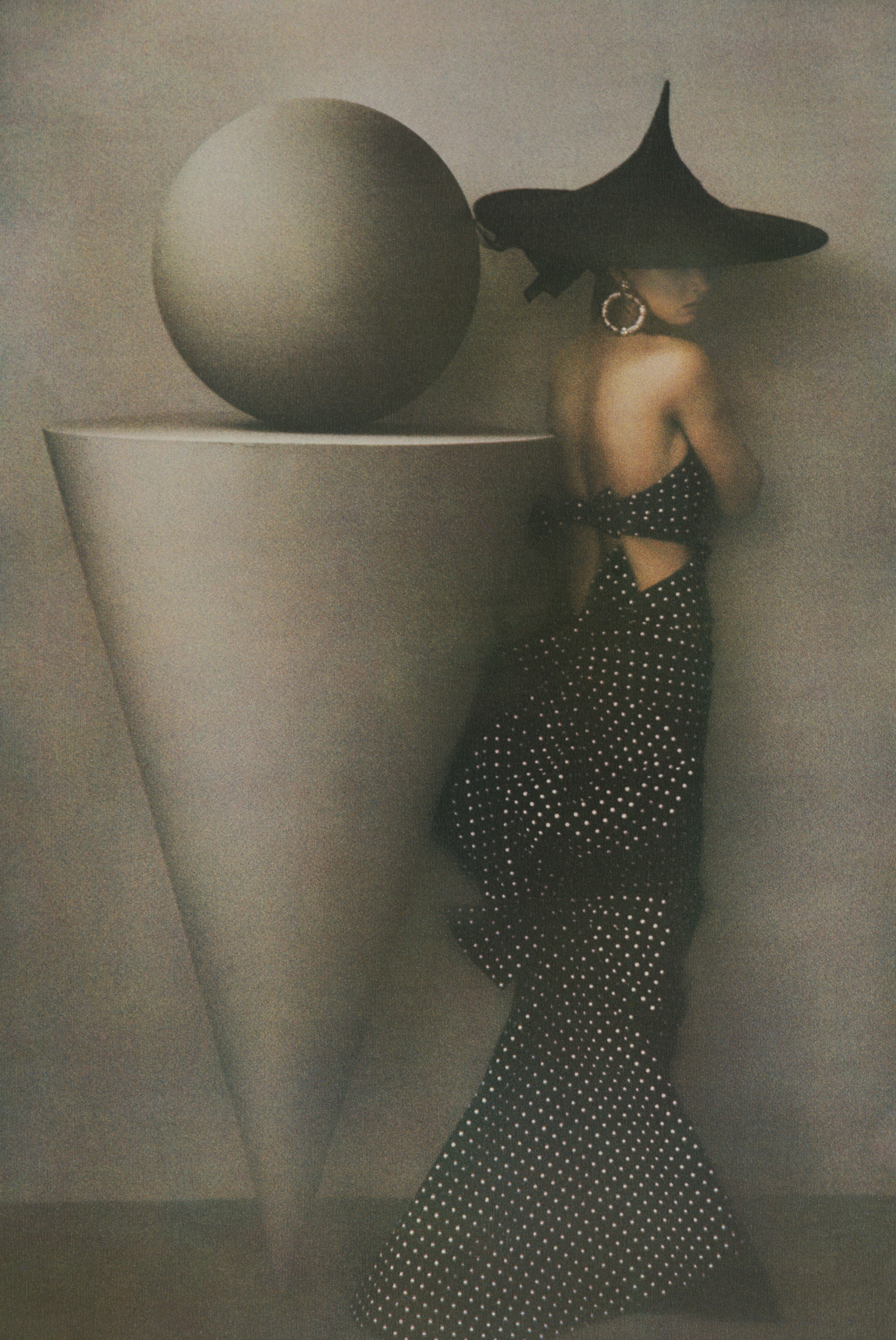

My Country is a series of conceptual works that zoom out to a national scope. The works are produced as color screenprints, lending them a gorgeous painterly quality. The images depict national monuments, each interrupted by a hazy black or red line that, for Faustine, represents the history that is omitted in these grand commemorations of white men. The Washington Monument pokes out of a black haze (George Washington was a slaveholder); “The Great Emancipator,” Abraham Lincoln sits on his great chair bisected by a Black line, evoking the role African Americans played in their own emancipation. The embedded critique is as deeply patriotic as the proud possessive nature of the series’ title, My Country, asserting belonging and stressing the need and right of all Americans to understand the full picture of how our democracy was built so we can understand how to hold on to it.