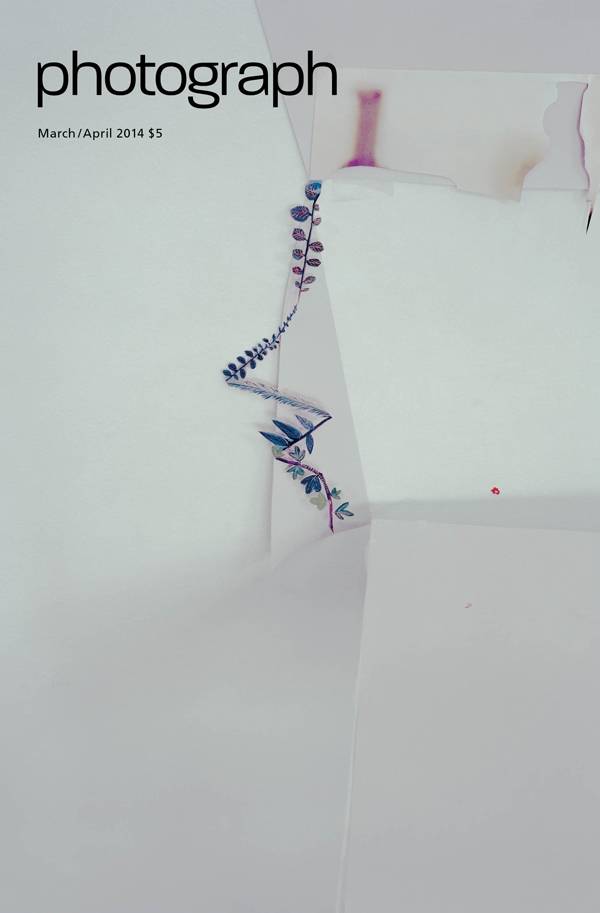

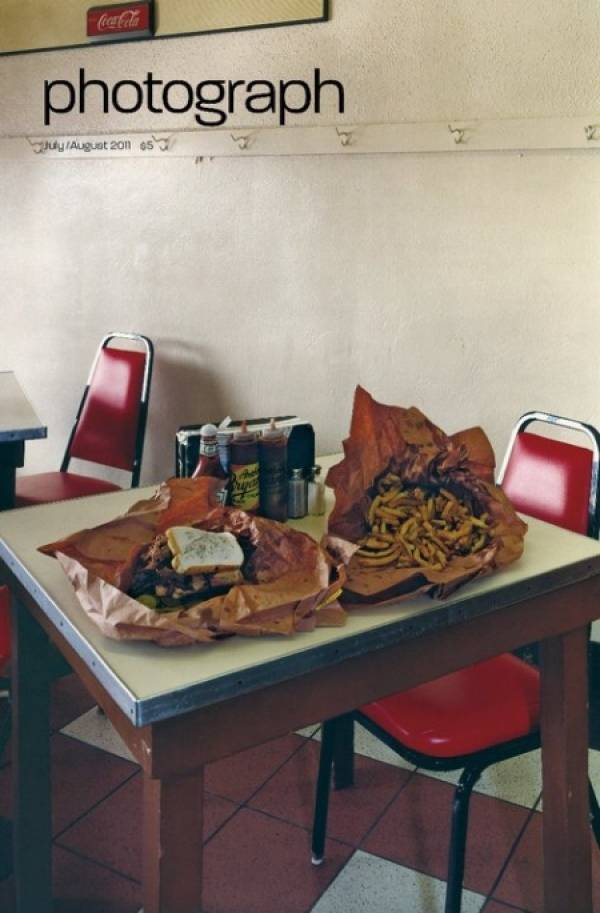

In a remarkable story by Italo Calvino, a reluctant amateur photographer follows an emotionally fraught path from making snapshots, to portraits, to nudes, and finally to photographing photographs themselves. It’s a postmodern progress, if ever there was one, and it illustrates the seemingly inevitable turn of contemporary photography toward self-consciousness about the medium. And if the photographer was once a painter, like Laura Letinsky, it’s unlikely she would ever have had the naïve impression that photographs open a window directly on the world. She would already have known that photographs are as much constructions as paintings are, and just as pleasurable to explore for their sleights of hand. Letinsky’s pictures have always contained other pictures, or at least had other pictures standing behind them. As Joseph Carroll, whose Boston gallery is showing Creases Turn Sour, a selection of her most recent work (April 2 to May 17), points out, her post-meal still lifes of the remnants of convivial get-togethers refer to a rich tradition of 16th and 17th century moralizing about the vanity of wealth and the fleetingness of human happiness. Yet she understood how much photography can add to this tradition: a heightened sense of the relationship between order and chaos (and their close bond in the experience of pleasure), an immediacy that makes an implicit claim on memory, and a malleable sense of the picture’s space, how easily it slips in and out of the illusions it seems to foster. “I am very aware of how photographs work to instill desire,” remarks Letinsky, “and that desire stimulates more picture making.” Like Calvino’s photographer, she has found that her ultimate subject is photographs themselves — how they work and what we expect of them. The cover photograph is a perfect example. Untitled #47, from her series Ill Form Void Full, contains all of Letinsky’s signature subtleties: the luminous atmosphere, the seductive surface of a design ad, and the ambiguous sense of space and arrangement. But this is a different kind of tableau, and the subject is not a scene but a fragment of an image — a picture within a picture. It’s not revealing too much to say that it is a bit of a photograph of a Matisse painting. In an obvious way, both painting and photography become mere signs in such an image, referring to their generic status. More particularly, though, Letinsky seems fascinated with how these reproduced images circulate to stimulate desire, not really for the things themselves but for a way of life in which such images have a place. Most people don’t have a Matisse in their Martha Stewart living room, but in the world of representations, a Martha Stewart living room and a Matisse (or a Gerhard Richter or …) belong together. Comments Letinsky, “I am perplexed and intrigued by the overlap and dissonance between art and being,” adding, “In a commoditized world of images, such experience is impure. My photographs seek to capture that.”

Categories