The film director Alfred Hitchcock used to complain about the typical dream sequences in movies: so often they were hazy and out of focus, all gauzy filters and slow dissolves. The meaning and logic of a dream may be elusive, he argued, but visually it is precise and full of detail. A lock of hair curling just so. Light on a face. The texture of a tablecloth. A scratch on a car door. “I wanted to convey the dreams with great visual sharpness and clarity – sharper than the film itself,” he said of the dream in his film Spellbound (1945). The finest technicians in Hollywood made it real. With its lucid images, incongruous juxtapositions, and crazed logic, that sequence may be as close as cinema gets to the disarming power of dreaming.

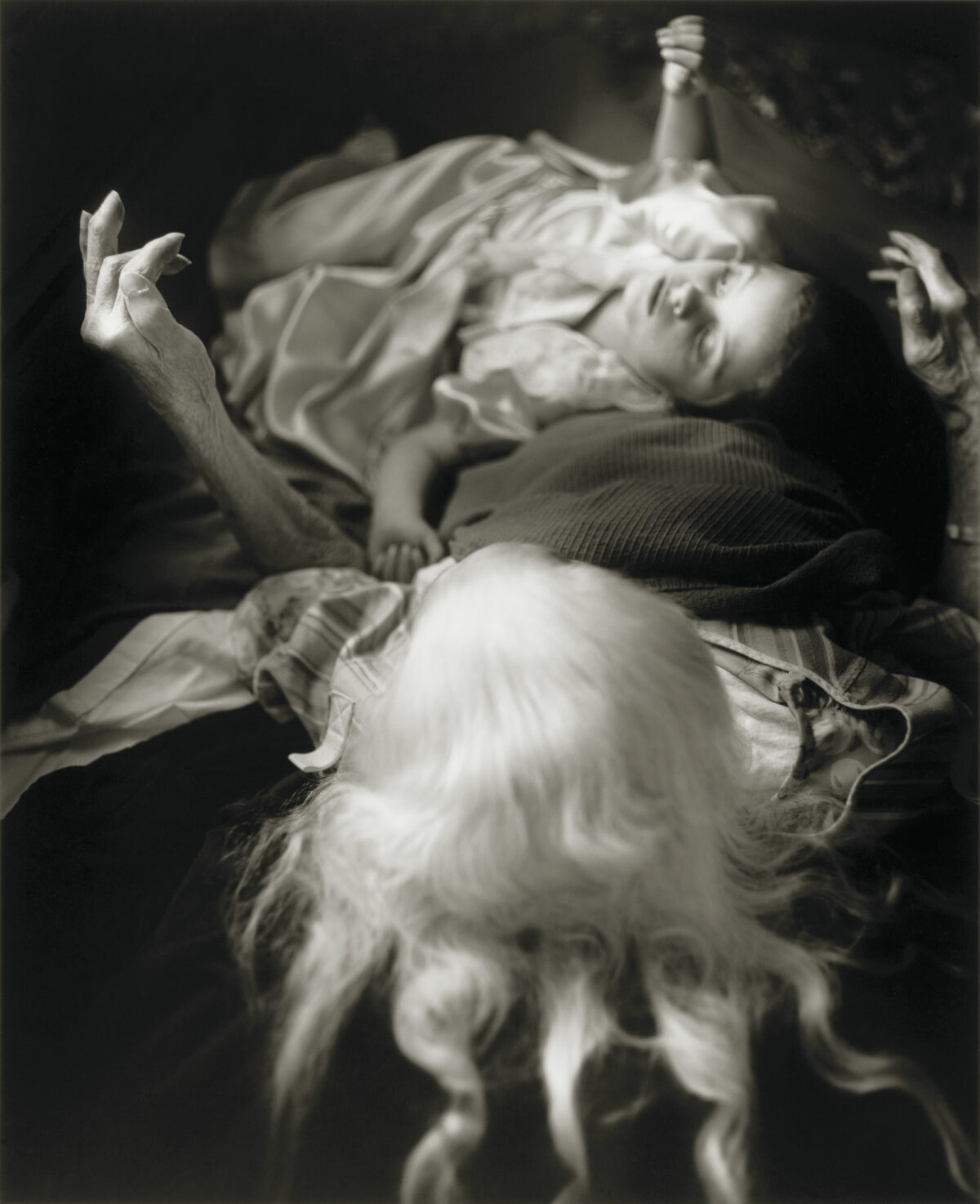

I have come to think that Robert Cumming’s photography is dreamlike in the sense Hitchcock was after. His strange, vivid images made throughout the 1970s, have a stealthy procedure and consciousness all their own. They seem to know exactly what they’re doing and present it clearly, but they are puzzling. A slice of bread appears to be embedded in the skin of a watermelon. A steel bucket is suspended in its fall from a wooden chair, and we see it from two different angles at the same instant. A truck, photographed head on, has a sign taped to it stating: A Truck Is An Object. One can be charmed by such inscrutable visions, while scratching one’s head.

Each of Cumming’s images would begin with an idea (and it’s best not to ask where that came from). The idea would be translated into a meticulous drawing on paper. In the process of drawing, Cumming would be thinking through the practicalities. Then he would turn to making the necessary props and sets. When everything was ready, he would light the scene, set up the camera, and make the image.

Cumming began his artistic life as a sculptor, and like many artists, he picked up photography as way to document his work. For convenience, he would send photos of his three-dimensional work to open-entry sculpture exhibitions, and often it would be accepted. He realized that a good image of a sculpture might be better than the real thing, even though it can be misleading. But the camera’s power to both describe and mislead soon began to fascinate Cumming, and photography became the end point of his practice.

This shift, from object to image, was widespread in 1970s art making. Far less typical was the sheer quality of Cumming’s images. Most other artists working conceptually had a rather perfunctory attitude to the medium, and the images they made had a rough and throwaway feel. But Cumming honed his photographic craft working with an exacting 8×10-inch view camera.

The results have all the pictorial and tonal assurance of the very best large-format photography. Edward Weston or Frederick Sommer would have been impressed. They also have a hyper-real quality, satisfying the forensic gaze invited by Cumming’s strange objects and situations. You can see everything, right down to the patina of each nut, bolt, nail, and screw. This excess of clarity only deepens the pictorial mystery. It might all feel a little labored if the work wasn’t so funny. Cumming invented a world where the absurd and the profound are natural companions, a world of innocence and guile, plain speaking and gentle betrayal. Why shouldn’t a deep philosophical point about the nature of appearance and human expectation take the form of a well-crafted gag? On the occasion of his Whitney exhibition in 1986, Cumming put it like this:

An art work for me is a number of things; an out-loud (objectified) speculation, an answer to the rhetorical questions of the physical universe, a personal antidote to the chaos of the world and finally, a gesture of interpretation and good will to my fellow humans in hopes that these intuitive inventions may somewhere generate a small degree of enlightenment. I depict objects usually; they’re my vehicle. Strung together over the years, they’ve been my tickets of passage.

The bewildering brilliance of Cumming’s ideas and the perfection of his images marked him out as a serious and original artist. His photographs were exhibited widely and eventually collected. His self-published books, with titles such as Picture Fictions (1973) and A Discourse on Domestic Disorder (1975), gained a small but cult following. My first tantalizing glimpse of his work came via a battered copy of the landmark 1978 Museum of Modern Art catalogue Mirrors and Windows: American Photography since 1960. Then I saw one of his images on the cover of an old group show catalogue from a 1979 show at SFMOMA titled Fabricated to be Photographed. But by the end of the 1970s, Cumming felt he had achieved pretty much everything he wanted with photography. His final major project, in 1978, was shot not in his backyard, as many of his earlier photographs had been, but on the back lot of a Hollywood movie studio. There he found an entire ready-made Cumming World: a full-size fake submarine built in cross sections so its interior could be filmed; the motorized fin of a shark (made for Jaws II); meticulously painted backdrops; and perfectly realized corners of rooms.

After a decade of photographic work, Cumming all but put his camera aside. To this day, he concentrates on drawing, painting, and sculpture. For quite a while, various factors conspired to push his photographic achievement into the shadows: it didn’t have the typical look of conceptual art as it came to be reevaluated in the 1990s and 2000s; with its sideways relation to sculpture and performance, it didn’t square with “purist” photography either. And of course, the art market really doesn’t like it when an artist appears to change direction. Eventually, Cumming became known for work in other materials, although the photographs formed a key part of his retrospective shown at the Whitney Museum and elsewhere in 1986.

Thirty years on, a whole new generation is discovering Cumming’s photographs. The nature of the work – mixing media but somehow remaining quite true to photography’s core ability to show the world without explaining it – has begun to make perfect sense once more. Indeed, his practice resonates with the work of many younger photographer-fabricators, from Lucas Blalock and Peter Puklus to Shannon Ebner and Anne Hardy. Cumming himself remains admirably bemused by this. When I described to him this new following, he raised a slow and quizzical eyebrow. “Oh? Good!” I suspect that is the exactly kind of reaction he would like viewers to have to his images.

In response to the renewed interest, Aperture published The Difficulties of Nonsense last May, a beautifully produced survey of Cumming’s best photography. (Full disclosure: I interviewed Cumming for the book.) It is edited by Sarah Bay Gachot, who has also organized The Secret Life of Objects, the first major exhibition of this work for many years, on view at the George Eastman Museum through May 28.

In the rush to establish the histories of photography, it is the pictures that are difficult to classify that are often overlooked. But when those histories prove inadequate, as they eventually do, those are exactly the kinds of images that are rediscovered. At long last, Robert Cumming’s vision is retaking its singularly satisfying place.