Robert Mapplethorpe’s name seems to grow in mythic proportion with the years. In 2014, complementary exhibitions of his work were mounted in Paris, at Le Grand Palais and Le Musée Rodin, causing a sensation and attracting long lines during the entire run of both shows. Now, Los Angeles is in store for a Mapplethorpe extravaganza of its own: in mid-March, dual exhibitions of his photographs will open at the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, an unprecedented collaboration between the two institutions to show the work of a single artist simultaneously. The very fact of these concurrent exhibitions further secures Mapplethorpe’s deification in the art world firmament.

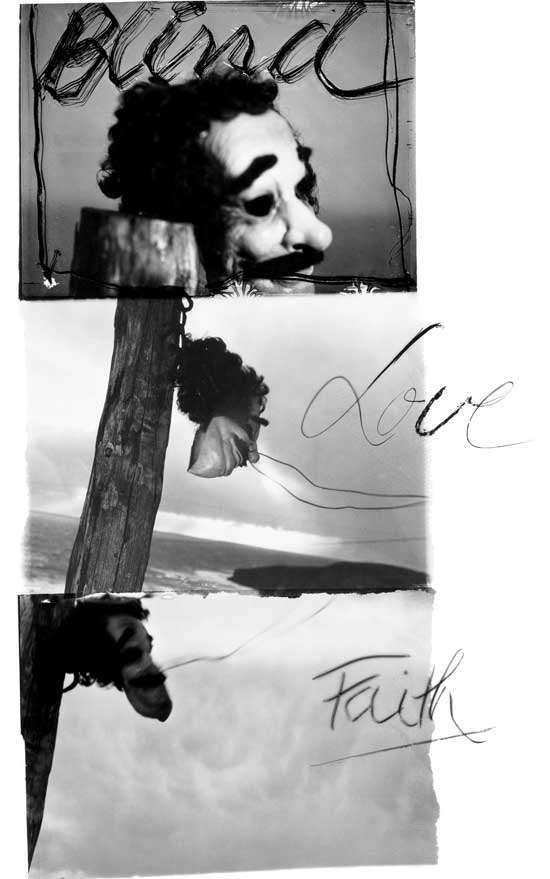

For me, Mapplethorpe’s name still conjures the taunting, mysterious, erotically charged atmosphere of Lou Reed’s “A Walk on the Wild Side,” written about the Warhol factory regulars – Candy Darling, Jackie Curtis, Joe Dallesandro, and Gerard Malanga – who congregated in the back room at Max’s Kansas City. It was there, circa 1970, that artists, rockers, fashion designers, and young socialites gathered, alongside drag queens who animated the nightly soirees with an antic, theatrical, sexually ambiguous, and decidedly urban flamboyance – paving the way, not incidentally, for what later became identified as the LGBTQ community. Mapplethorpe and his muse and psychic twin, Patti Smith, came of age in the back room at Max’s, and also at the Chelsea Hotel, where another historic contingent of bohemian arts and letters resided – William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, and Leonard Cohen, to name a few of the writers, poets, and musicians they got to know along the way.

In 1972, Mapplethorpe turned to photography as his defining medium, even though it was not considered much more than an applied art at the time. I am fond of pointing out that, in the early 1970s, growing respect for photography in the art world occurred simultaneously with the growing visibility of the gay rights movement. Perhaps it was just a coincidence of timing, but throughout the 1970s, Sam Wagstaff – Mapplethorpe’s lover, mentor, and patron, and also one of the earliest photography collectors – was instrumental in elevating the stature of photography in the art world, while Mapplethorpe brought homoerotic representation in photographic imagery to the museum and gallery wall. By the end of that decade, these two men were at the intersection of photography and the gay sensibility; both had an indelible influence on photography’s own coming of age.

Mapplethorpe was not the first to photograph the male nude in homoerotic terms – there was, after all, Thomas Eakins in the 19th century, Baron von Gloeden and F. Holland Day at the turn of the 20th century, and George Platt Lynes in the mid-20th century. But these forerunners could not show their work in public places because of the cultural taboos that led to strict laws against homosexuality.

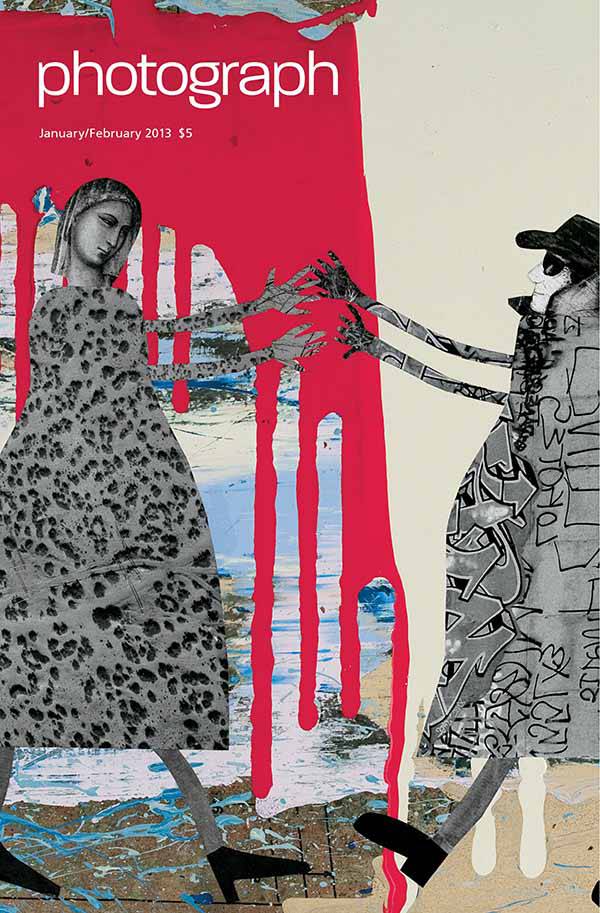

When dealer Holly Solomon was reluctant to show Mapplethorpe’s homoerotic imagery, he proposed the idea of dual shows – his portraits at the Holly Solomon Gallery and his x-rated work at The Kitchen. Germano Celant, the Italian curator and art historian, attended both shows – the artist’s first serious gallery exhibitions, in 1977 – and understood how powerful a gesture it was for Mapplethorpe to “come out” in his erotic photographs, not only as a person but an artist. “Mapplethorpe definitely collected pornography,” Celant said, in Robert Mapplethorpe and the Classical Tradition, published by the Guggenheim in 2004. “But these images were a completely different input in the art world, as works of art. And that’s what makes his work so radical. After him, it became easy. A lot of people started doing it. But in the beginning Mapplethorpe was the one who forced the galleries to show his work.”

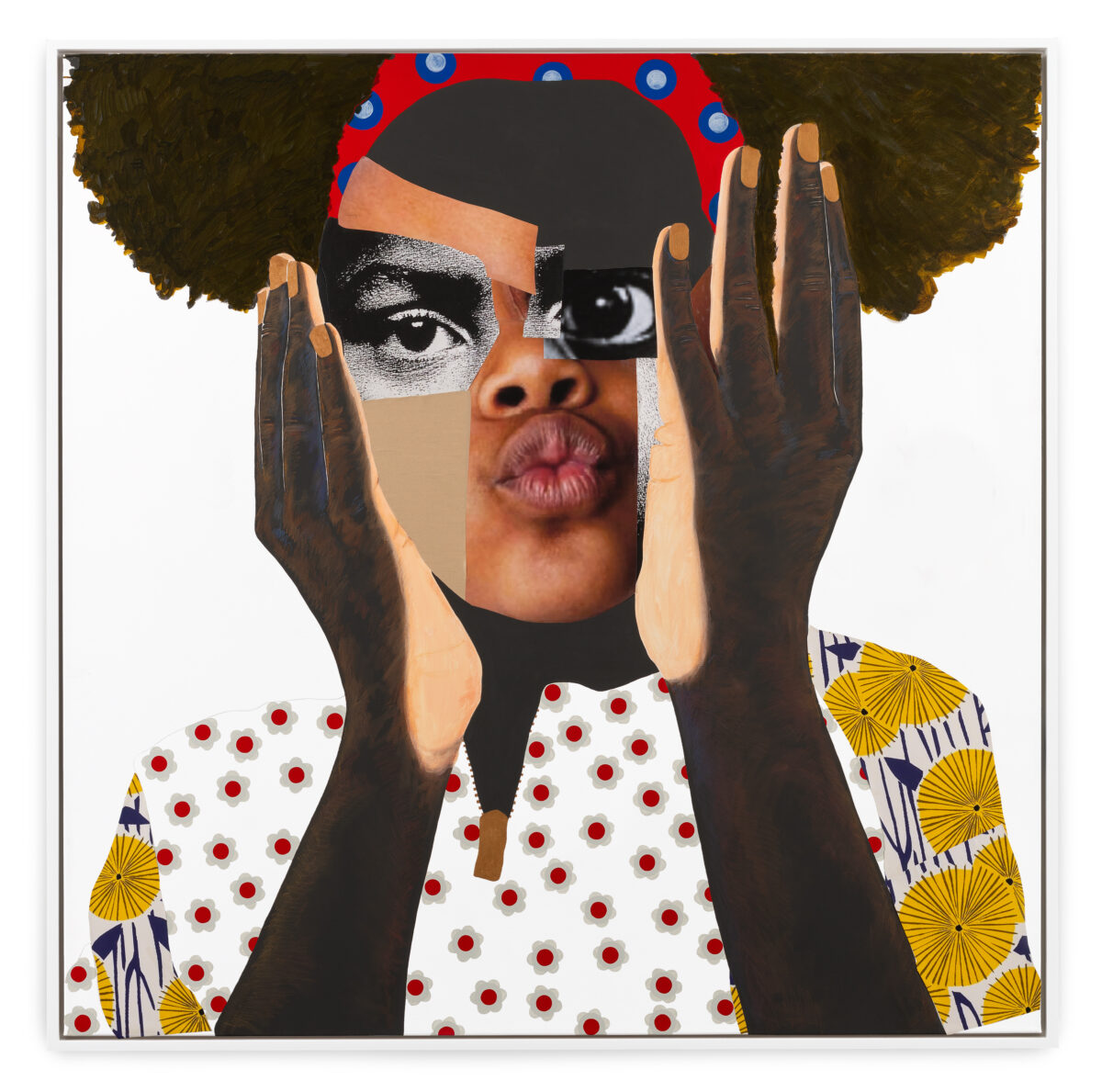

Mapplethorpe was a pioneer in his depiction of male genitalia in detail, and also in his representation of S & M sex. But here, too, he was not alone. His contemporaries Jimmy De Sana, George Dureau, Peter Hujar, and Arthur Tress, pioneers one and all, were mining homoerotic territory in their own work. Mapplethorpe was simply more adept at positioning himself for cultural recognition. Philippe Garner, a veteran photography expert at both Sotheby’s and Christie’s in London, got to know Mapplethorpe well as his reputation grew. In an email to me several years ago, he identified Mapplethorpe’s public persona rather nicely when he said: “Robert was the 1970s leather-clad equivalent of the great dandies and decadents of the fin de siècle – Beardsley, Oscar Wilde, Huysmans.” Mapplethorpe’s persona was a seductive calling card, but his association with Sam Wagstaff was his secret weapon: Wagstaff knew everyone in the art world and introduced Mapplethorpe to all the right people, adding a useful Machiavellian tutorial along the way, coaching him to navigate the upper echelons of society to his advantage. As Carol Squiers, longtime curator at the International Center of Photography, told me in 2011, “Sam gave Robert class, and Robert gave Sam sex appeal.”

Mapplethorpe’s photographs were scandalous in his lifetime – at once highly aestheticized yet immediately and unapologetically transgressive, from his African-American male nudes to the homoerotic imagery that veers toward the sadomasochistic, all of which only added to the lurid patina of his notoriety. Yet it is clear today that his male nude studies embodied the deep current of social – and sexual – change that rose so powerfully to the surface of his era. He was expressing erotic longing in aesthetic terms.

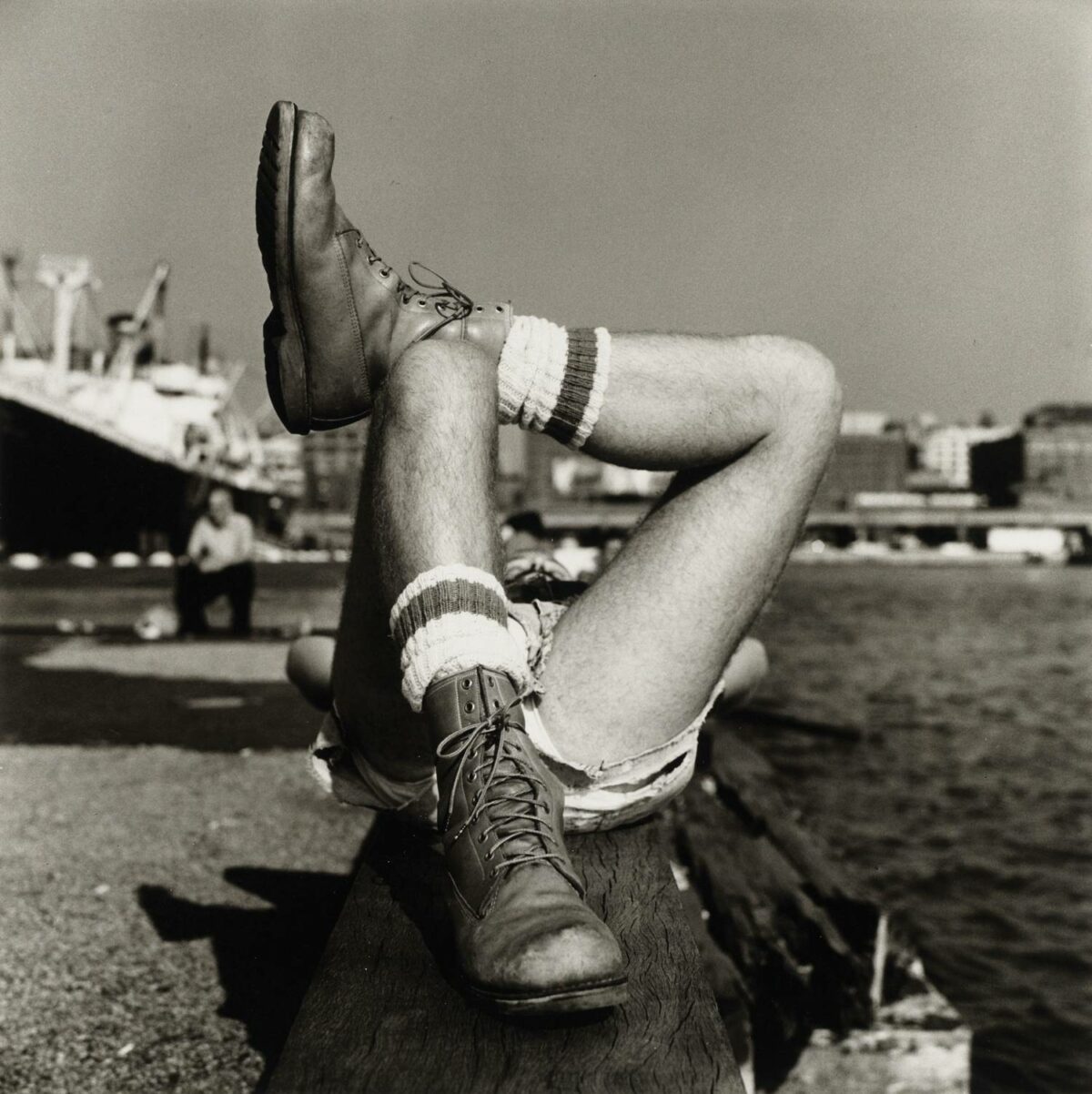

Mapplethorpe cruised the gay bars in the West Village along the river after midnight, almost every night, on a mission to find sexual partners who could double as models. Photographing his conquests in the morning light allowed the lingering physical passion and tactile experience of the night before to inform his scrutiny of the subject in the clear light of day. The camera gave him a measure of distance to see his subject openly, more objectively, without awkward emotional embarrassment. Mapplethorpe often spoke of loving his subjects while he was photographing them, even if he didn’t love them, or even recall their names, afterward. “I can fall in love with the subject and not be personally involved,” he told Janet Kardon, then curator at the Philadelphia Institute of Contemporary Art, in 1989. Robert once described making love and taking pictures, both, as forms of losing himself: “When I have sex with someone I forget who I am. For a minute, I even forget I’m human. It’s the same thing when I’m behind the camera. I forget I exist.”

What strikes me about those early photographs, in particular, is that he aimed so high in visual terms while manifesting something true about his own erotic desire. It isn’t that his photographs summon desire; they aestheticize it in photographic terms. His regard for the medium of photography itself – for the visual image – was equal to the exaltation of his subject.

Not only was there critical hostility to Mapplethorpe’s male nude studies, the subject of male nudity itself was disparaged. Reviewing a group show in which Mapplethorpe was included called The Male Nude at Marcuse Pfeifer Gallery in 1978, Gene Thornton spoke for the conventional public: “There is especially something to be said for old-fashioned prudery when the unclothed human body is a man’s body,” he wrote in The New York Times. “There is something disconcerting about the sight of a man’s naked body being presented primarily as a sexual object.” Many photographers in that show were heterosexual men and women. Their male nudes were not presented as sexual objects. But the cultural fear of homosexuality was still pervasive in 1978; merely looking at a male nude had the taint of lurid thoughts in the eye of the beholder.

All to say that, over the years, the controversies surrounding Mapplethorpe’s work only propelled his reputation. In 1989, the year of his death, the big cultural brouhaha over censorship of his work was fueled by Senator Jesse Helms on the floor of the U.S. Senate, only to have a (deliciously) adverse affect. It made the very idea of Robert Mapplethorpe just that much sexier. Still in the end, his work speaks for itself: the quality, substance, and originality of his photographs is what secured his place in art history.