Upon entering Lyle Ashton Harris: Our first and last love, on view through July 2, one is drawn in, first and foremost, by the visual power and formal complexity of the work. Using photography as his primary medium, the conceptual artist explores and complicates issues of identity as societally and culturally defined by race, sexuality, and gender. Organized into thematic groupings around his newest series, Shadow Works (begun in 2017), the exhibition presents a range of works grounded in performative portraits of friends and the artist himself, including his breakthrough series Americas (Triptych), made in 1987-88, when he was still an undergraduate at Wesleyan University, and a personal archive of images and ephemera that provides throughlines connecting all aspects of the artist’s practice.

Harris’s time as a graduate student at the California Institute of the Arts, where he studied with the photographer and theorist Allan Sekula, shifted his way of thinking and gave him the language and voice to speak from and about his personal experience as a queer Black man. Drawing on his friend bell hooks’s assertion that photographs made for and by Black people are a crucial counteraction to pervasive racist stereotypes, and inspired by his grandfather, an economist and prolific amateur photographer, Harris began documenting his life and community. When the artist moved to Ghana in 2005 to teach, he stored almost two decades’ worth of accumulated photographs and video footage at his mother’s house. When he returned to the United States in 2013, he rediscovered the collection, which he refers to as the Ektachrome Archive. The archive captures Harris’s personal history, but also serves as a window onto the overlapping circles in which he moved in the late 1980s and 1990s, specifically the art world and the gay community, which was being devastated by the AIDS crisis. Among the cast of characters he depicted are artists Renee Cox and Iké Udé and curator Thelma Golden. Harris’s Ektachrome Archive, like his 1994 series The Good Life, selections of which are also on view, transcends and expands on the meaning of family and demonstrates that intimacy and belonging are not exclusively biological.

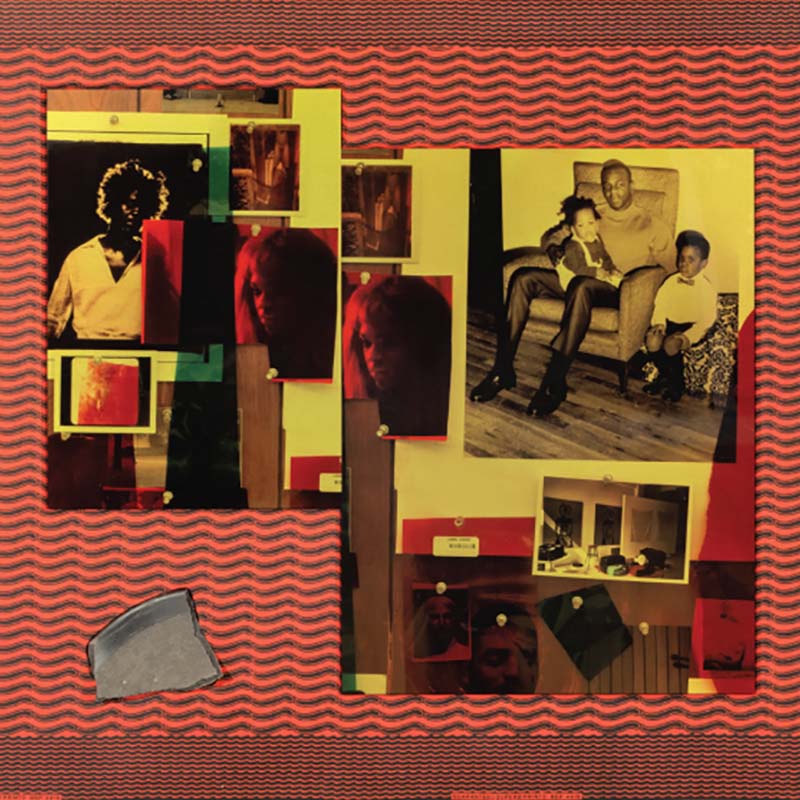

A centerpiece of the exhibition, which is co-organized by the Rose and the Queens Museum, is Obsessao II (2017), a wall installation drawn from the Ektachrome Archive and rooted in Harris’s Blow Up series (2004-2019) of mixed-media collages. As the artist stated in an interview published in Lyle Ashton Harris: Blow Up (Gregory R. Miller and Co., 2008), “I had finally found a means to say many things at once as opposed to distilling them into single images.” Photographs – some printed on fabric, others repeated at different scales – are interspersed with inscribed Post-it notes, newspaper headlines, and other ephemera (two nearby cases display similar material, including his Wesleyan student ID, SX-70 Polaroids, and postcards from family and friends). Also incorporated into the collage are red, yellow, blue, and green polycarbonate gels, often hand-stenciled with letters in gold, which Harris uses in performances and as filters to create atmosphere through color. The imagery refers to an expansive mix of public and private memories and experiences that touch on friendship, love, intimacy, and work.

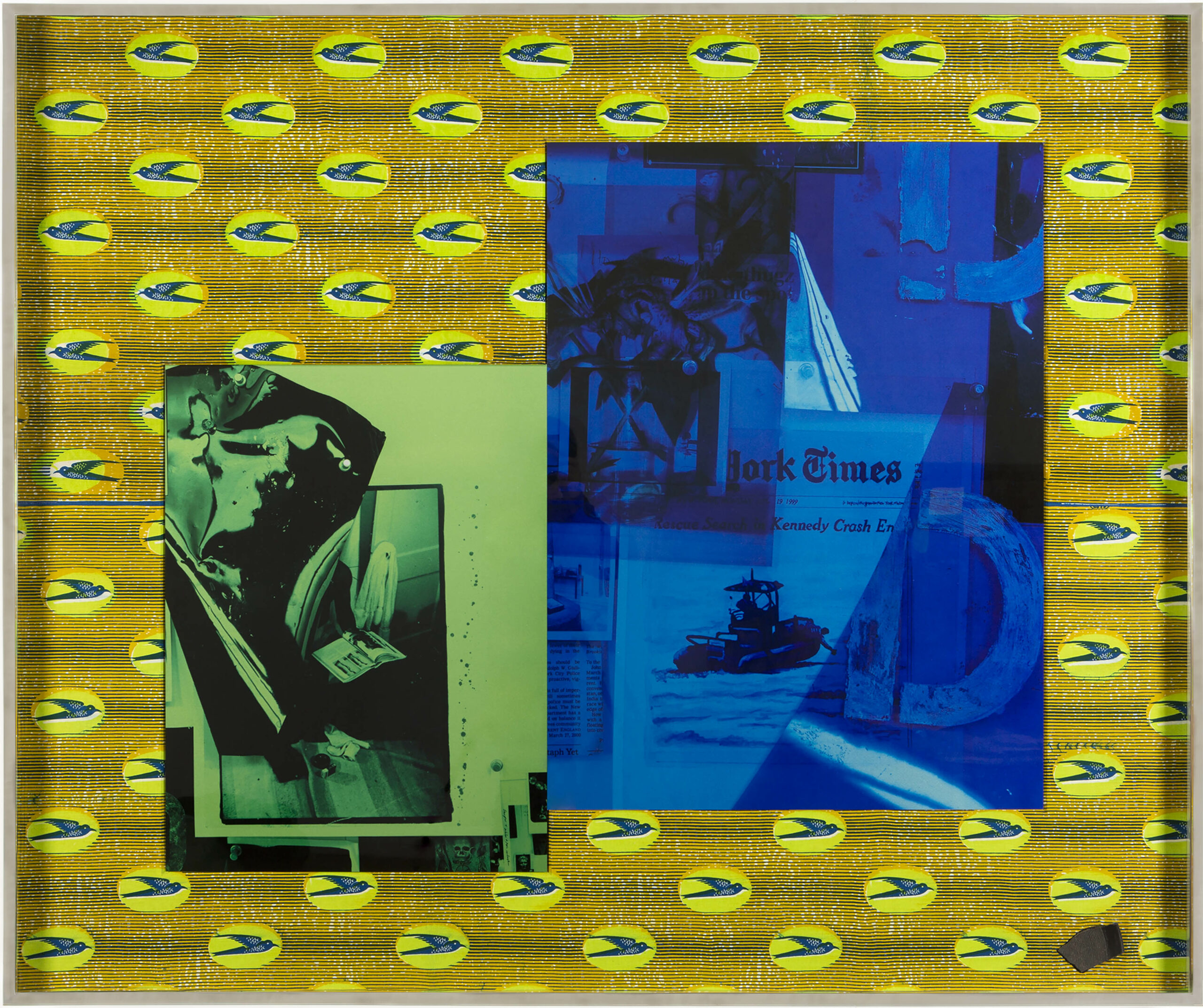

Harris’s Shadow Works are composed of close-up photographs of the wall collages printed on aluminum panels using the dye-sublimation process and embedded, often alongside a single personal object, in colorful Ghanaian textiles. Containing the controlled chaos of the wall installations, the artist creates graphic visual layers, as demonstrated in Untitled (Red Shadow), from 2017, the first work from the series, which includes two details of a collage captured in raking light to which is affixed a small, almost imperceptible print of lilies, the letter “s,” stenciled twice in matte black, and the patterns in the fabric – all of which play against the reflective quality of the aluminum. These elements are tied together by the visceral red color that connects the work to earlier series, including The Watering Hole (1996), for which Harris created a collage of images and ephemera related to the violent murders of 17 gay men of color by the serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer between 1978 and 1991. Other Shadow Works weave together the recurrent themes in Harris’s oeuvre – self-portraiture and performance, family and legacy, hate and violence, love and desire, past and future. In its strategy of using these recent works as anchors, the exhibition deftly demonstrates the myriad ways in which they intertwine and connect every aspect of the artist’s practice and life.