Luke Swank’s photography career began late, when he was 40, and ended early, upon his death at 54. But in 14 years in the 1930s and ‘40s, Swank accomplished quite a lot. His subjects were diverse – a steel mill, a circus, a Frank Lloyd Wright house – and his work met wide acclaim on both coasts. During his life, the Museum of Modern Art showed his photographs on three occasions.

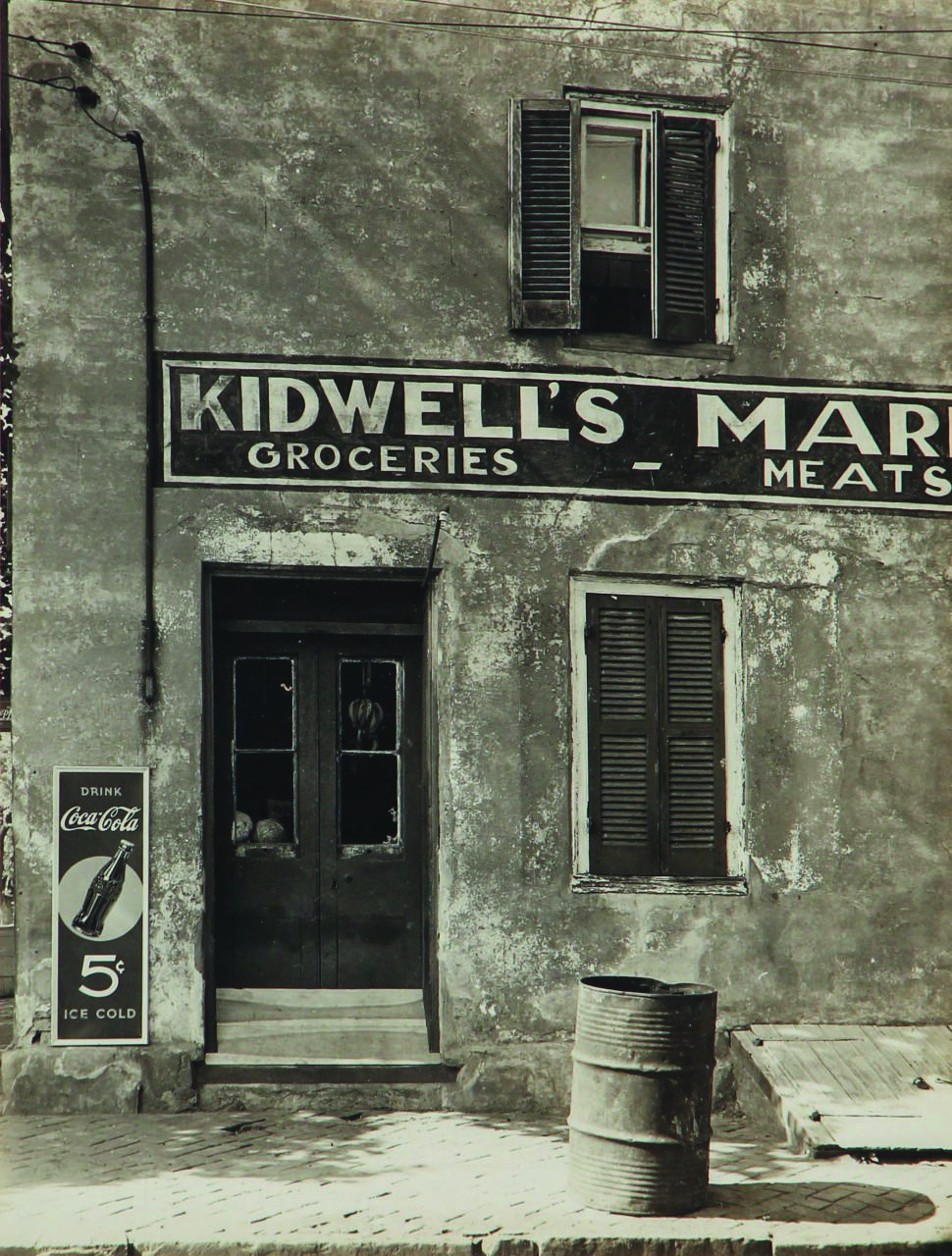

Swank’s work is often notable not for what he photographed, but rather, for how he photographed – his ability, as Vanity Fair editor Frank Crowninshield put it in a 1934 announcement of a Swank exhibition at New York City’s Delphic Studios, to reveal “what is particular to American light and air.”

That quality was front and center in the 20 unostentatious vintage prints at L. Parker Stephenson Photographs this fall, depicting quiet scenes of American homes and businesses. Their subjects are quite ordinary: a wrought-iron fence, a wooden barn, a cobblestone walkway, a flight of stairs on a hillside. People appear infrequently in the frames, and when they do, they’re specks in the landscape.

Unlike Swank’s early photographs of industry, which encapsulate a more romantic style, these photographs embody the kind of realism exemplified by Alfred Stieglitz and Paul Strand. Though less dramatic, there is often something in them – the texture of a wall, the interplay of light and shadow, or the faraway presence of an anonymous figure – to make a viewer look twice. These photos don’t demand our attention, but they do deserve it.

Despite his success, Swank’s work was, for decades, overlooked, in part due to his early death. That began to change in 2005, with a major exhibition at the Carnegie Museum of Art. While that exhibition showed the full range of Swank’s practice, this tightly curated selection presents a kind of snapshot of Swank’s artistic interests and approach. It reveals a photographer willing to work slowly and carefully to reveal the subtle beauty of everyday life.