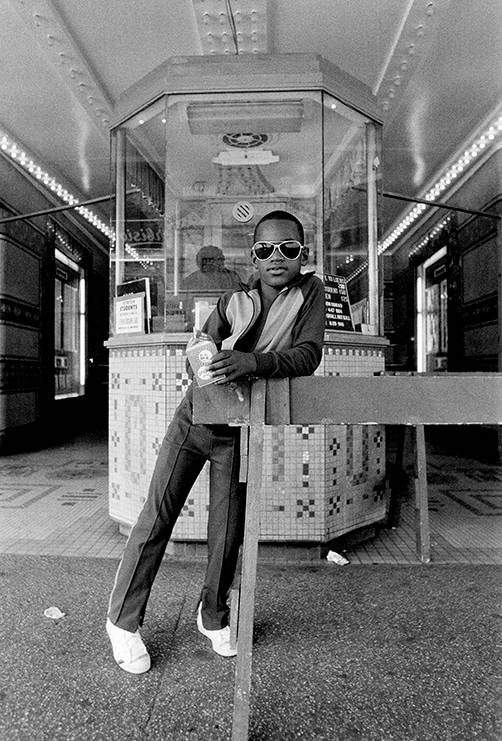

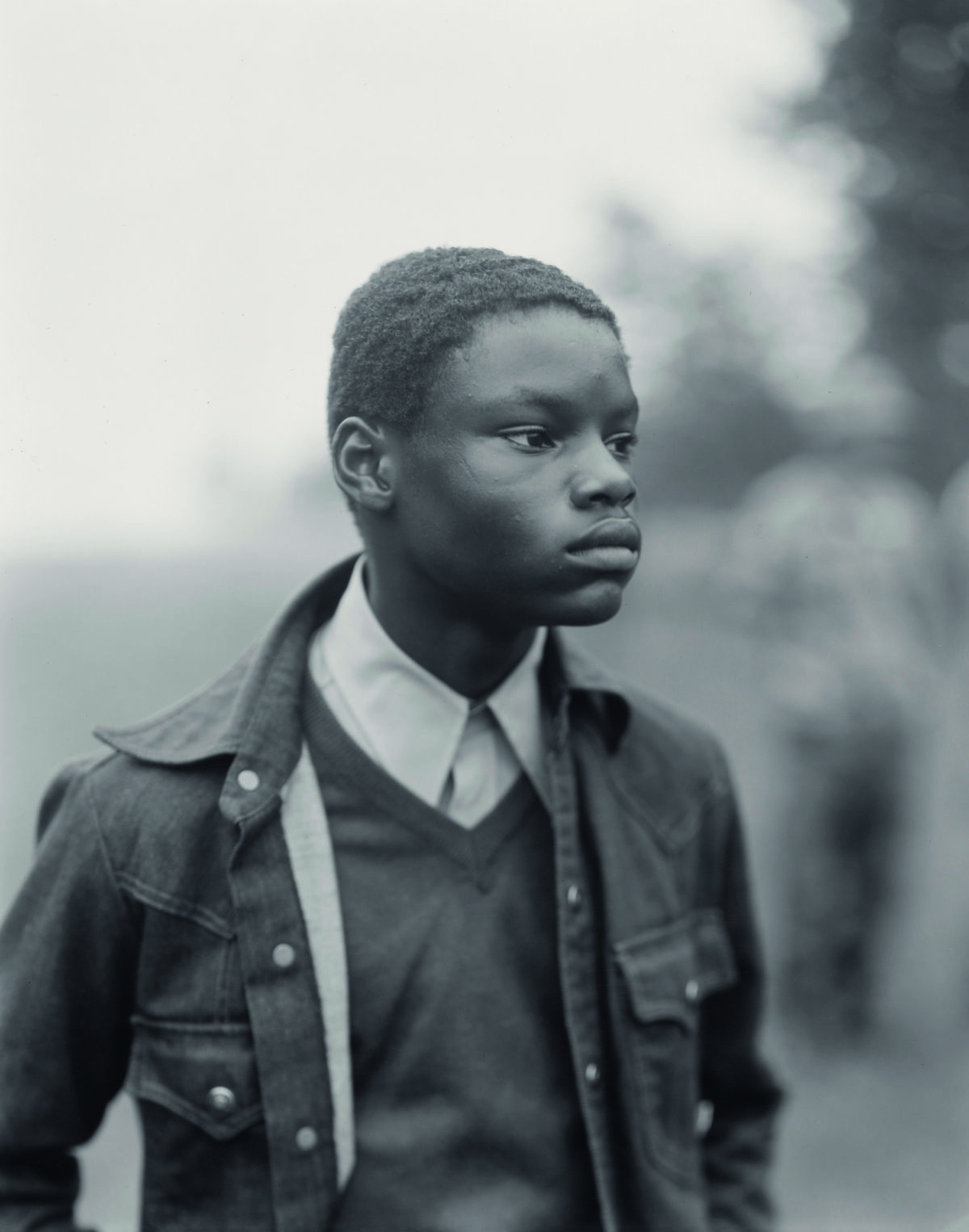

Through a host of projects beginning with Minor League (1993) and Treadwell (1996), Andrea Modica has established herself as perhaps the foremost black-and-white photographer of her generation – although it is more accurate to say that her preferred medium is the platinum print. Her most recent publications are 2020 (TIS Books, 2021) and Theatrum Equorum (TIS Books, 2022). Works from these two series are on view at the Berman Museum of Art at Ursinus College (PA) until December 11.

Lyle Rexer: I wanted to ask you first of all about the series 2020, which seems uncharacteristic. It is a catalogue of abandoned cardboard boxes, and it seems to invite us to think about the subject a bit like Bernd and Hilla Becher’s typologies of industrial structures: the same but different. I suppose it has a relation to the almost forensic pictures of human skulls you made for Human Being (2001), but I always think of you as a narrative photographer, not a conceptual one.

Andrea Modica: I have never started a project with a clear concept or intention, but rather with need and fascination. I view 2020 as autobiographical, reflective of a specific time in my life. I had just bought a house and during the worst of the pandemic, most of the things that came into it were ordered and delivered. You recall we were told not to touch anything, so the boxes were left in the driveway, and the titles of the photographs reveal what was in them – everything from two dozen roses just before Valentine’s Day to a microwave at the new year. After I emptied the boxes, I left them in the driveway and photographed them over time. The book itself resembles an agenda or a diary in its size and format.

LR: There’s something quite poignant about these boxes, weathered and worn.

AM: They’re organic; they decay, like animals. At the Berman Museum, the curator, Deborah Barkun, has gridded the photographs. Interestingly, they appear more conceptual and less narrative.

LR: Poignancy and fascination inform your extended project Theatrum Equorum, which deals with an equine hospital near Bologna, Italy, and especially its surgical procedures. Given the relative paucity of serious attempts in the art world to deal with animal reality – not just the politics of species loss – this is an astonishing meditation. How did it happen?

AM: I had regularly been visiting this town near Bologna, when I discovered there was a horse hospital. I got to know the doctor, and he gave me a tour. I was all questions. I was especially fascinated by the recovery boxes – simple stalls filled with shredded art magazines, medical journals, and junk mail, where the animals recover consciousness after surgery. In the United States this would have been a much more antiseptic, padded facility, but the shredded paper seemed to work well for the animals, as well as the images. I photographed there off and on for nearly eight years.

LR: Many of the horses are under anesthesia, but that said, there is an incredible stillness about the photographs, not deathlike but uncanny.

AM: Some of that, I suspect, is the result of the equipment I use. After the horses come out of surgery, they are still for only about ten minutes. I was using absolutely the wrong camera for that situation – an 8×10 view camera. It was a stupid idea, just as it was a stupid idea to use that camera to deal with a subject that I knew nothing about – baseball – when I photographed a young Derek Jeter and a young Jorge Posada in the minor leagues. But the big camera, in combination with platinum printing, can produce images that seduce the viewer, creating an almost physical connection to the subject. To a large degree this shapes the photograph’s meaning.

In terms of the process, the cumbersome act of positioning the camera and dealing with the lens and film holders forces quick decisions. There was an incredible adrenaline rush every time I photographed the recovery boxes, and sometimes the horse would awaken, and I just couldn’t get the job done in time. And I’m scared of horses. They are big and imposing creatures! But I regarded the recovery boxes as my opportunity to deal with these magnificent living animals with my camera of choice.

LR: Theatrum Equorum also includes still-life photographs of the surgical tools – both individual instruments and groups, pre- and post-procedure. Some of them recall the precision of the Neue Sachlichkeit of the 1920s and others, scenes from a David Cronenberg movie. They provoke conflicting emotions, to say the least.

AM: The still lifes capture the full nature of the place. In many of the post-surgical images, the tools are arranged neatly and systematically. Ordinarily, the surgeon sets up the tools carefully, both before and after a procedure. But in an emergency, as in the case of colic, which can come on quickly and be fatal, there is an explosion of stuff – bodily matter – and the team is moving very quickly. It can seem chaotic in comparison to a routine knee operation, for example, and the photographs reflect that. Again, as with the photographs of the boxes, the titles are very important.

I photographed only one animal that died, and it happened while the anesthesiologist stepped away for a moment, while I was photographing. I had to go tell him. It wrecked me. I stood by helplessly weeping as they tried to revive the horse.

LR: You mentioned that you couldn’t set up lights with the animals, but the lighting in many of these photographs is remarkable, almost Vermeer-like in its softness or like Caravaggio in the encroaching darkness.

AM: The recovery boxes have windows up high, so the horses can’t see outside when they wake up. This overhead natural light was a gift from the photo gods. I’ve also spent a great deal of time in Italian churches, so I was affected by church light, which is also primarily overhead. I felt a connection between these places. You mention Caravaggio. There is so much information in that darkness.

LR: Set into the cover of the book is a still image taken from videos you shot of the horses after they had been sedated but before they became unconscious. It’s as if you are asking us to look directly into the consciousness of the animal, to grasp a different way of experiencing reality.

AM: The horses are essentially paralyzed from the anesthesia, but their eyelids remain mobile, and their eyeballs are often moist and teary as they are going under. The eyes never completely close, even after the surgery begins. In the reflection of an eye, you can watch the activity of the operating room, as the team prepares for surgery. This is the moment I film.

It seems to me that the eye is the most familiar part of a horse, and it is where I can relate to the animal’s vulnerability and find some affinity. Under anesthesia we relinquish complete control, and I’m guessing I’m not the only one who finds this terrifying. I’ve always gravitated towards photographic subjects that frighten me, figuring there’s plenty there for me to learn (making a “good photograph” has always been secondary, but admittedly an addiction unto itself). The process of shooting for Minor League is a good example of this kind of motivation, and the same is certainly true for Theatrum Equorum.

Lyle Rexer’s most recent book is The Critical Eye: 15 Pictures to Understand Photography (Intellect Press). He teaches in the BFA, MFA, and MPS programs in photography at the School of Visual Arts.