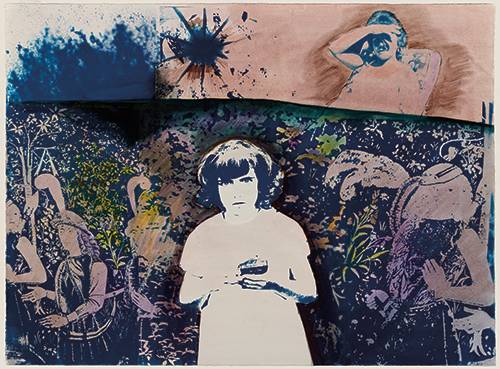

When asked how he started experimenting with photography, Belgian artist Pierre Cordier described a scrappily romantic experience: he was in the military, in Germany, in 1956, and he was writing a love note to a girl named Erika, using nail polish on light-sensitive paper. Once developed, the painted portions of the paper became colored while the rest of the paper turned dark. Cordier proclaimed himself the inventor of the camera-less chemigram process, essentially a painting-photography hybrid, and he became quite good at extracting strange colors and eccentric compositions. A few of these hang in the first gallery of the Getty’s exhibition, Light, Paper, Process: Reinventing Photography, on view through September 6, including such sensual images as Chemigram II, 1976, in which the reddish squares in an uneven grid look like slabs of excavated earth. Work by Man Ray and Robert Heinecken hangs in that gallery, too, early experiments with photo process that still read as surprising, raw discoveries.

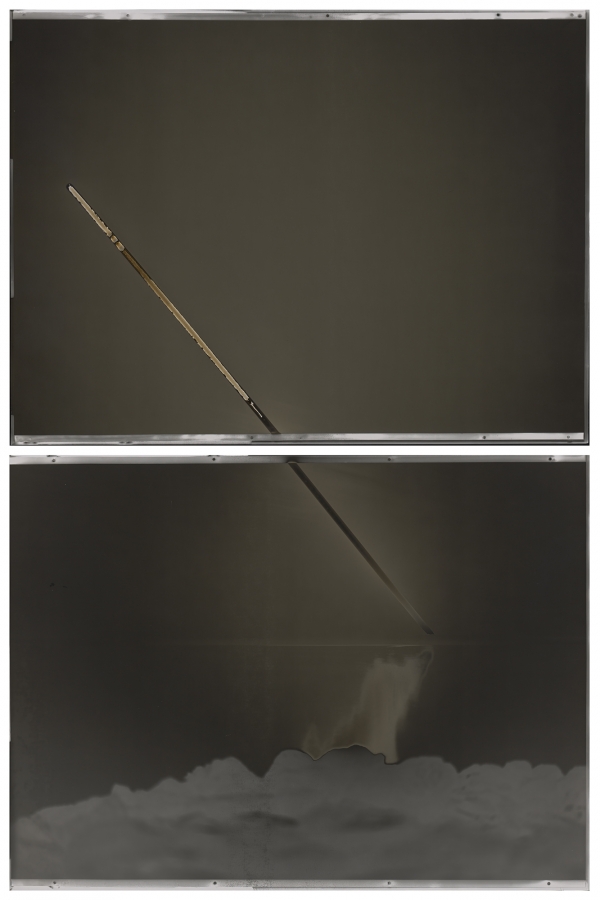

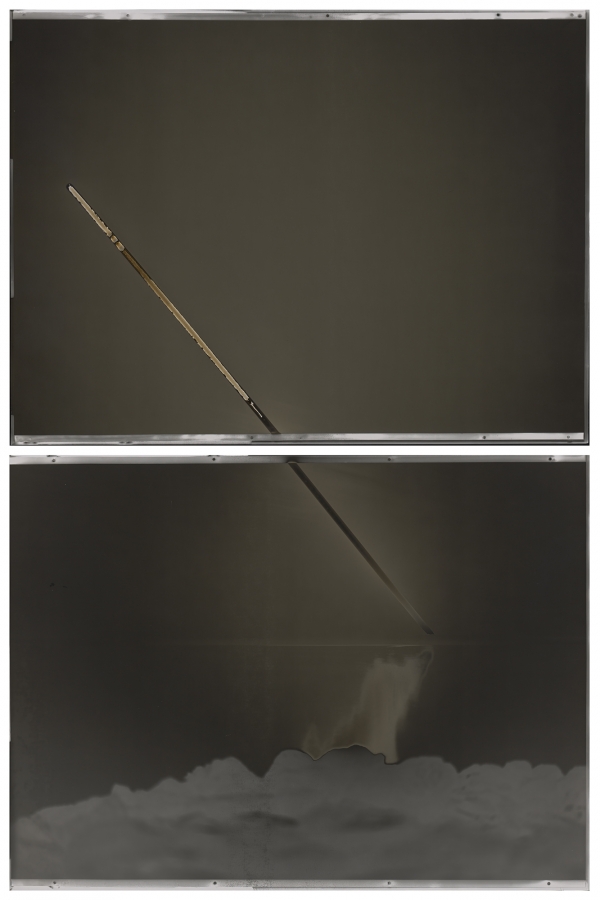

The subsequent galleries feature the contemporary “reinventions” at the core of the exhibition. The seven artists on view have rejected the smooth predictability of the digital, but their analogue experiments feel more calculated, less risky than their historical predecessors. Alison Rossiter makes her elegant, intentionally flawed washes by exposing expired photo paper, mostly made before the 1950s. The results are gray, brown, or off-white expanses, nostalgia pared down to its barest elements. Lisa Oppenheim adds silver toner to her developer, so that her Heliograms and Lunagrams, made by exposing photo-paper to the sun and moon, shimmer subtly. Chris McCaw photographs the sun, loading enlarger paper rather than film into his camera so that the lens acts like a magnifying glass, and the light literally burns the paper. Tastefully positioned burn holes or gashes dash across his paper negatives. John Chiara is more dramatic, and some of his vibrant landscapes, processed as negatives, are super-saturated inversions of nature. Matthew Brandt works with landscape too, sometimes mixing ashes or debris — or chocolate cake, in the case of one silkscreen — into the ink he uses to print his intensely stylized images.

But even these experiments are hard to read as radical. Perhaps this is because they arrive in the wake of a generation of conceptual photographers who put critical content front and center, even when experimenting with process (Brian Weil, Cindy Sherman, David Wojnarowicz). Perhaps it’s also because some of the images are suspiciously close in look and feel to the formalism dominating the painting market at the moment. Israel Lund’s approach to color can be compared to Brandt’s, Jacob Kassay’s to Oppenheim’s. Overlaps like these make the work in the exhibition feel in line with the zeitgeist, a savvy, safe approach to reinvention.