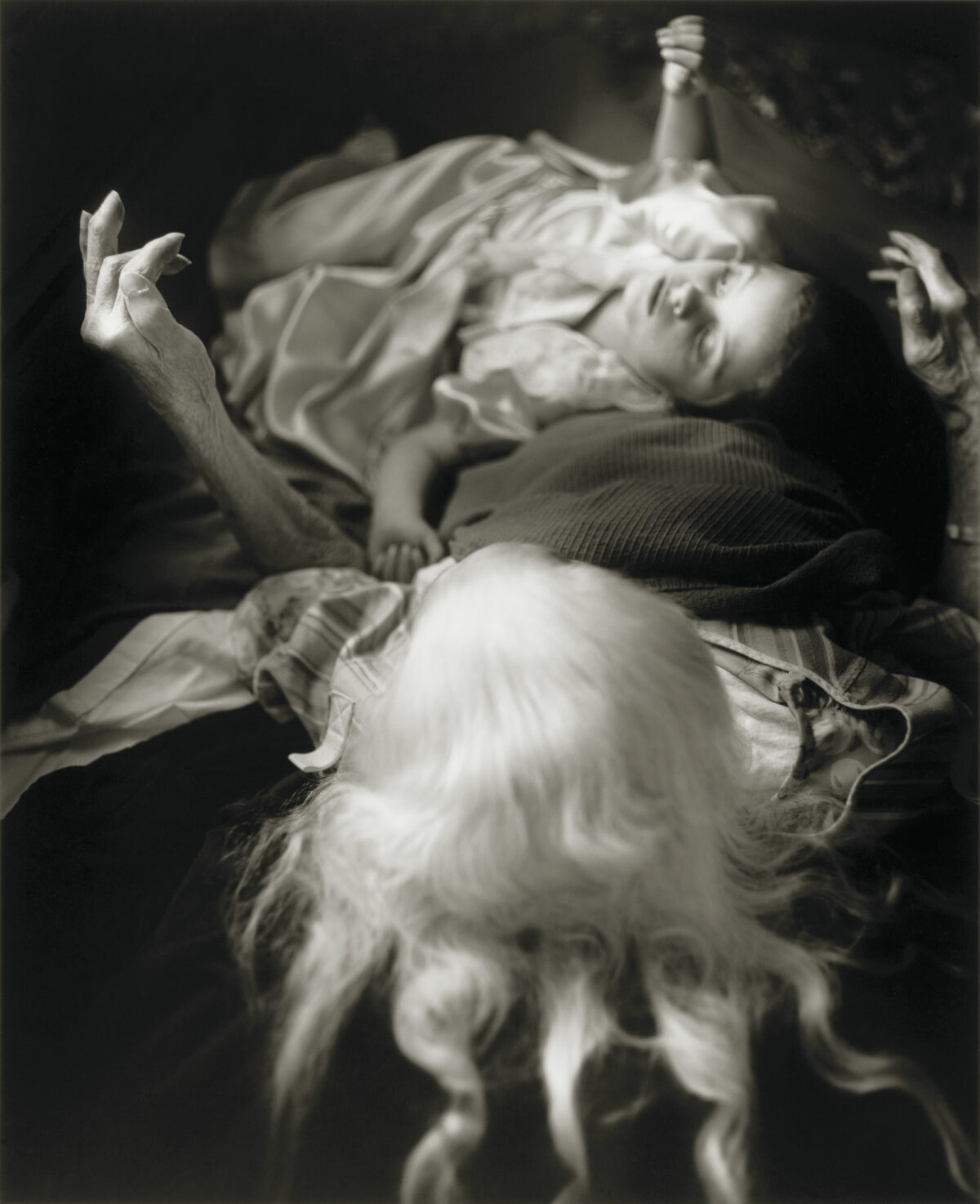

The history of photography in the United States needs a new map. Instead of New York, Chicago, and San Francisco, this one would include such places as Rochester, NY; Champaign-Urbana, IL; Gainesville, FL; and Penland, NC. This alternative itinerary has defined the career of Bea Nettles, whose traveling retrospective, Harvest of Memory, is on view at the George Eastman Museum (January 30-June 14, 2020) and subsequently at the Krannert Art Museum in Champaign, IL (August 27-November 28, 2020). That career has itself defined a series of challenges to conventional photography, including everything from stitched works and Tarot-card sets to gum-bichromate printing and cyanotype. Nettles’s groundbreaking self-published manual Breaking the Rules: A Photomedia Cookbook (1992) went through three editions and was as important for photographers seeking alternative approaches as The Joy of Cooking was for generations of household chefs.

Lyle Rexer: I think of you as a mentor and inspiration to many artists, giving them permission to think outside the box, but you yourself had important mentors who encouraged you to break the rules.

Bea Nettles: They were so important to me. Robert Fichter, for example, was the best thing that ever happened to me.

LR: A photographic artist who has not gotten the recognition he deserves for the creative role he has played.

BN: Absolutely. I was studying painting and printmaking at the University of Florida in Gainesville, and I had put off taking a required course in photography. I finally took a course with Fichter, and his first assignment was: take an object and photograph it in as many ways as possible. I was right at home. He didn’t want acolytes but people who were willing to try any and all approaches. I had been to the Penland School of Craft [in North Carolina] and wanted to take an elective ceramics class, but Fichter kept pushing me toward photography. He knew I needed money to buy materials, and so he suggested I become Jerry Uelsmann’s assistant. Which I did, and learned all Uelsmann’s techniques.

LR: You recently retired from the faculty at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. That’s also where you received your MFA. But I gather the ride was somewhat bumpier then.

BN: At that time there was no degree in photography, and I was in the painting program. Art Sinsabaugh taught the photo classes, and he was a purist. I was already ostracized for studying painting, and as I was already hand coloring my prints, that made me a sort of pariah. He said: Prove to me you can print. By that he meant according to the zone system of black and white, which I have never been taught. I vowed not to take any more photo classes, but I needed to print, and he effectively locked me out of the darkroom once I was no longer his student.

LR: It reminds me of the reception [photo artist] Betty Hahn got when she was stitching her prints. Women’s work!

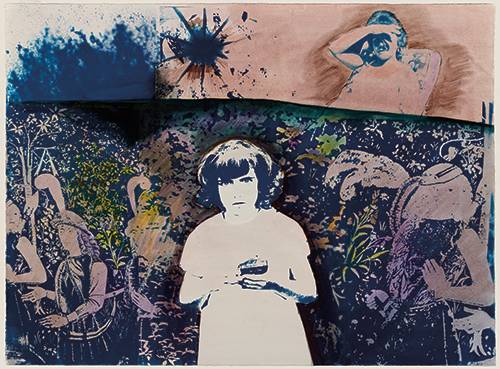

BN: I know all about that because I was sewing, too. The piece Skirted Garden (1969) is a good example. It was in my thesis show and had the added element that in order to see all of it, you had to lift the skirt.

LR: A compromising gesture for skeptical faculty if ever there was one.

BN: I eventually continued to print in a student’s basement. Later I went to the head of the graduate program and petitioned for another darkroom, which I built. Sinsabaugh hated all this, and it was a great irony that I would end up taking his position at UI after his death.

LR: Also ironic considering that you already had work included in the landmark exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Photography Into Sculpture (1970). Along with MoMA’s Information (1970) exhibition, it is one of the shows I dearly wish I had seen.

BN: Peter Bunnell, the curator, had heard about my work through Robert Fichter, and Bunnell actually flew out to Illinois to visit my studio. Can you imagine that happening now?

LR: Just send me the JPEGs. Getting back to this idea of women’s work, I can see why so much of what you have done would have been hard for a largely male audience, mostly consistent in their views of photography, to engage. Not simply the antiquarian or domestic aspects of darkroom processes but also your concentration on subjects such as pregnancy, your children, and mythology, especially goddess imagery. All this would have been grounds for discrimination.

BN: Not so much discrimination, maybe, as dismissal. As I said, my work has had champions, but not many reviewers, who can be quite snide. In the past, reviews have involved comments like “Nettles dreams on.” At the same time, you have to understand the situation of the period. I was one of the original 13 photographers represented by Light Gallery, but I was the only woman. And in 1980, when I was on the faculty at the Rochester Institute of Technology, there were 48 men and two women who were photography instructors. This led to an embarrassing situation. On the occasion of a faculty exhibition, they took a departmental photo of us all lined up, which required several sequential shots with a 4×5-inch camera. The other woman, Kathleen Collins, was on sabbatical, so I decided to stand in for her, further along in the sequence. The photo was printed as an announcement, and no one seemed to notice until it circulated. It seemed to call attention to this absurdly gendered situation.

LR: As long as we are on the subject of photo sequences, I have been intrigued by your interest in books and bookmaking. You taught bookmaking for years, and your approaches are anything but the familiar format of: essay, picture, picture, picture.

BN: My first book combined my mother’s poems and my images in a three-ring binder. After graduate school, I became more and more interested. I learned how to bind, and I eventually obtained access to run an offset press. When my husband [Lionel Suntop] was founding Light Impressions [in 1970], the important publisher for photography, I saw project proposals by everyone from Larry Clark to Ralph Gibson. It became natural for me to think sequentially. I taught book-making for a semester at the Visual Studies Workshop, and this led to a humorous situation. One challenge to the class was to critique their books without looking at them. Obviously I was interested in the object character of books, especially their tactility. We could touch them, smell them, listen to them, even taste them, but not see their contents. We all had stocking caps over our heads when in walked a tour group led by Nathan Lyons [founder of the Visual Studies Workshop], who was dead serious about everything photographic. I have no idea what he must have made of this room full of blindfolded page sniffers.

LR: I can’t imagine, but I know that this is going to be my next critique assignment!