Penelope Umbrico is that rare artist who has built a significant reputation largely through public commissions and installations at institutions from the Musée des Beaux Arts in Le Locle, Switzerland, to New York City’s Grand Central Station. Two important projects are on display simultaneously in New York. Her wall installation in the exhibition Anna Atkins Refracted is part of the New York Public Library’s 175th-year celebration of the English cyanotypist (through January 6). Her installation Monument, a collection of, among other elements, disassembled television screens, is featured at BRIC Media House, the Brooklyn art and performance space (November 29-January 20).

Lyle Rexer: So I was thinking about the facetious definition of a string quartet – a good violinist, a bad violinist, a failed violinist, and somebody who hates the violin – and relating that to the world of contemporary art photography. As an artist who regularly appropriates photos from internet platforms, you’ve probably been accused of being the cello player – of hating photography, in other words. I remember hearing that after Suns from Sunsets from Flickr appeared.

Penelope Umbrico: It’s not true! I LOVE photography! How could I spend so much time culling and cropping photographic images if I didn’t really love the medium? I do, however, engage critically with it, sometimes more critically than others.

LR: In Suns there’s a lot of intentionality, from cropping to printing to display formats.

PU: Right. And for that project, especially, I’ve been criticized in the most conservative ways. After it was shown at the New York Photo Festival in 2008, for example, there was an entire Flickr discussion board accusing me of being lazy for borrowing parts of photographs without attribution. Of course, the pictures were all perceived to be authored, but in fact they are all very much the same, and the fact that so many people take the same scripted picture was the initial incentive for making the work. That project is about collective photographic practice, not individual authorship. Attribution would ruin it.

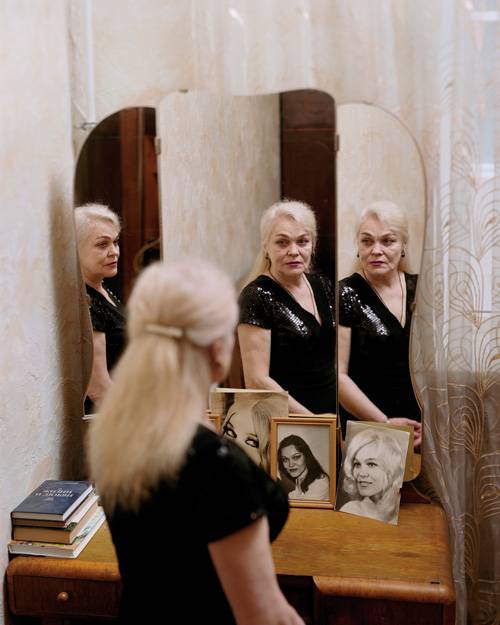

LR: How do you see these photographs in relation to TVs from Craigslist, for example?

PU: The Suns photographs are the opposite of those in TVs from Craigslist. The Craigslist images are throwaways. They are never intended to be “authorial.” But in fact these are the photographs in which you can find individuality and particularity. Caught in the reflections in the screens are glimpses of the messiness of actual lives. There is a humanity in those images that is wholly unintentional but very real.

LR: You did a lot of appropriation projects before Suns, but for me it has always seemed the crucial piece, a kind of jumping-off point for so much of the work that has come after, including now both New York installations.

PU: Yes, that’s true. The internet changed everything. For one, it gave me access to unlimited source material, and the screen became my studio, in a sense. And living and working through the screen made it become part of what the work is about. Everything we do, all communication, is basically mediated through the screen. The light pictured in those sun pictures is not sunlight – on the screen, it’s screen light. I think I first realized how important this was when I used the images from Suns for a screensaver titled Sun Burn.

LR: That’s counterintuitive, since the centered sun in all the flashing images seems like it should burn a hole in the screen.

PU: Yes, and it does! It’s a subversive screensaver, which you don’t actually need anyway. Better just to put the computer to sleep. But I like the idea of this frenetic electronic light keeping your computer awake. I’m thinking about the fact that the light from the screen is supplanting the light of that singular source, the sun – that the experience of natural light is subsumed to this universal non-place at which we all sit and stare.

LR: Screens are at the heart of the BRIC and NYPL pieces. It’s almost as if in different ways you are trying to take us inside the screen.

PU: Yes! I am intrigued by the idea of the black box, and the fact that we engage quite physically with these devices but know very little about what’s inside. And we are quite unaware of how they affect us. The screen in particular is thought of as invisible. But when it breaks, you get a glimpse of its materiality, of the stuff we are being affected by every day. I was thinking about Marshall McLuhan’s notion of the medium as the message, and I wanted to make some work about the physical materiality of these devices – in a sense, turning the black box inside out. Last year I did a kind of residency at the Gowanus E-Waste Warehouse, an electronics recycling facility in Brooklyn. Among other things, I took apart about 150 broken LCD televisions, and with those that still worked, I created a wall of TVs, all playing horror movies on their defective screens. I liked the idea of broken screens presenting broken bodies. I am creating something similar at BRIC except that the wall of broken LCD TVs can be programmed, so we’ll be live-streaming the news, and we’ll also be doing some other programming. For this exhibition, BRIC will also become a temporary e-waste in-take center, where people can bring unwanted devices and can take them apart, lay the parts out, and we’ll take a photograph. I’m calling it a Knolling Table. [Knolling is the process of arranging different objects on a surface and then photographing them from above.] Plus I will be making a new installation with the parts of LCD TVs people bring.

LR: Placed in front of each other, some of the screen films variously conceal and reveal the images as you move through the installation. The entire thing feels very physically precarious and visually unstable.

PU: Yes, I wanted to speak to the physicality of the screen and also our passivity in relation to it. In this work, you need to move around, to navigate the screens in order to animate them and see what’s there.

LR: This transforms the screen experience from a projection to an optical and physical event. It reminds me of how daguerreotypes work, and how the viewer has to shift the plane of the object in order to see the image.

PU: I hadn’t thought about that! But it’s relevant, especially to the work I am showing at the NYPL. I was thinking about the screen as replacing paper, and screen light replacing sunlight in relation to the work of Anna Atkins.

LR: But you didn’t make cyanotypes for the NYPL.

PU: Well, I wanted to do something about natural light, and I wanted to invert our experience of light in relation to the screen. And I also wanted to engage with the idea of the photogram as a record and a means of creating a taxonomy. So I scanned all the computer monitors and laptop screens I’ve taken apart, but I scanned them with the sun shining directly onto the scanner, into and through the screen. What I made is, in fact, a hybrid scan/photogram. I then used the Photoshop “cyanotype” filter to point to the active role of the sun in the work – a photogram – but also, to the active role of the digital screen and scanner. The screen becomes the place where the two light sources meet, natural light and the scanner’s light. As with Atkins’s cyanotypes of English algae, this is the record of an event of light. I like to think I am revealing what sunlight looks like from the other side. The way sunlight acts inside and through the screen is quite unpredictable, the scanned record of which reveals the particularity of each screen – along with its gridded pattern, you also see its flaws and fingerprints, the intimate history of the screen’s use.

LR: It also reveals you acting – for those thinking about string quartets – as a violin player, that is, as a photographer! And I have to say that the work is beautiful, that the 192 inkjet prints in the installation hold their own with Atkins’s iconic project.

PU: Thanks!